|

Feature

SPACE: ALIEN WORLDS

Finding Earth Analogues in Space: Q&A with David Stevenson

Plus! The top space news stories of 2006

|

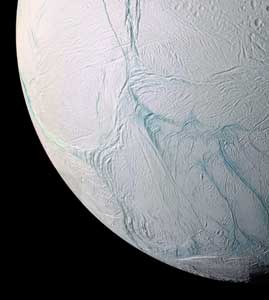

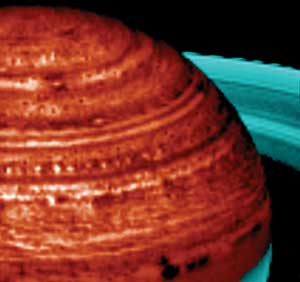

| Saturn’s moon Enceladus (above) boasts a surface marred with cracks. Astronomers discovered that the body is geologically active and has a giant geyser emanating from similar cracks in the surface. And in images of Saturn (below), astronomers noticed a “strand of pearls” formation, which turned out to be breaks in the planet’s cloud system. Images are courtesy of NASA/JPL/University of Arizona. |

|

In December 2005, David Stevenson, a planetary scientist at Caltech, spoke to Geotimes about what he considered to be the big stories in the field of planetary science. This year, Geotimes reporter Kathryn Hansen caught up with Stevenson to find out how those stories continued to make headlines in 2006, as well as about what Stevenson calls the “number one” story of the year: a newly discovered Earth analogue circling Saturn.

KH: What stories have continued to make headlines?

DS: There has obviously been a lot of interest in these [outer solar system] bodies, of which Pluto is one. We are now finding lots of these objects, and that is very interesting. Now in terms of what has actually been found in 2006, it’s incremental because the most interesting observations were made in the last three years.

KH: What is new about that story this year?

DS: There has been a fuss about what we are actually going to call these things. Recent activity at the International Astronomical Union [meeting] led to the decision that Pluto is now no longer considered in the set of planets as we’ve chosen to define them, so we really only have eight planets (see Geotimes, October 2006).

And we now have this other body that finally got its name, Eris. This object, which is larger than Pluto [now classified as a “dwarf planet”], was previously called Xena, which was just a joke name; it wasn’t intended seriously. Eris is the Greek goddess of discord, which I think is fun.

KH: Why did this issue over the definition of “planet” arise now?

DS: We have a revolution taking place in our understanding of the outer parts of the solar system. We’re learning a lot about the dynamics of these bodies by understanding their orbits, their sizes and what’s on their surfaces. They’re interesting bodies; they’re not just random chunks of ice and rock.

KH: Were there any new planetary science stories this year?

DS: I think Enceladus is the big story — not just because it is something really new, but also because it’s remarkable and surprising.

What they discovered is that Enceladus is active. Enceladus is a small moon orbiting Saturn; it is only 200 kilometers or so in radius, part rock, part ice, but the surface is a very bright, ice-covered surface. It is deformed — we knew that already — so it doesn’t look like a typical body of this size. It has cracks, it has smooth areas, but in addition, the Cassini spacecraft has found that it is active. Active means that there is material escaping Enceladus. You can think of it as volcanism or perhaps better as a geyser. So it is liquid that is converting into vapor, just like Old Faithful, leaving Enceladus (see Geotimes, February 2006).

KH: Why is Enceladus’ activity surprising?

DS: Well, it’s interesting because Enceladus is a small body, and we would not normally expect a body this small to be so active. There is nothing else like it in the solar system. There are larger bodies that are active, perhaps in a related way. The most obvious is Io, the large moon of Jupiter.

Io is volcanically active and we think that Io and Enceladus are doing it the same way. In other words the mechanism, the underlying physical cause for this activity, is the same.

KH: What might that cause be?

DS: These bodies are in eccentric orbits around the central planet, and as they go around in their orbit, they are flexed by the tidal force between the planet and the satellite. Therefore, you get a change in shape of the body as it goes around, and you get heating when you flex materials.

This is true of Earth, it’s true of rocks, and it’s true of ice. It’s nonetheless surprising because there are other bodies in eccentric orbits that don’t exhibit this, so this is a challenge to our understanding.

KH: What are the implications of activity on Enceladus?

DS: It is an indication that this body does have liquid water inside. So that gets the people who are interested in life excited. Now there is another body that in a very subdued way may be doing something similar, and that is Europa. Europa is the next moon out from Io in the Jupiter system, and we’ve known now for a decade that Europa is likely to have a water ocean underneath the ice shell. But Europa doesn’t exhibit nearly as much activity as Enceladus.

It is an example of ice volcanism or geyser activity of a novel kind. We haven’t seen this before — the body is so small. The interest, from the point of view of the chemistry and habitability in the solar system, is because of the water and the possibility of organic chemistry which started out life. Life is a little bit extreme in this context, but that doesn’t stop some people.

KH: Do you think there is a possibility of finding life on Enceladus or elsewhere?

DS: I’ve always been open to the possibility that the range of environments available for supporting life is greater than some people have advocated. If you say that habitability is tied to the presence of water and energy sources, and of course keep in mind that everything else that you think might be important will be there to some extent, in other words the periodic table … then I think there are many environments that in principle could support life. That’s not the same thing as saying that life has actually developed [on Enceladus]. I don’t think we know how to answer that question.

I think Europa continues to be an interesting environment, especially if you are interested in the development of life that is really quite different from Earth. But Mars is still the most attractive place to look [for life], and the reason is that Mars had an environment that was plausibly Earth-like early in its history — maybe not right at the surface, but a little bit down beneath the surface.

Links:

"Planets redefined: Pluto gets demoted," Geotimes, October 2006

"Tiny moon, gigantic geyser," Geotimes,

February 2006

"Exploring the Universe," Geotimes, December 2005

Subscribe

Subscribe