|

Web Extra Friday, February 16, 2007

NASA mission to study magnetic storms

|

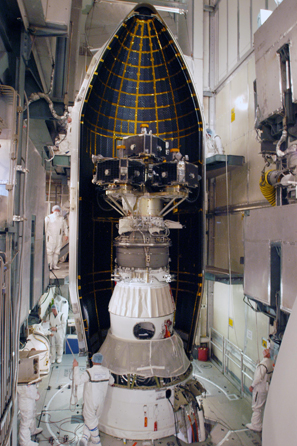

| Technicians place the five THEMIS satellites inside the nose of their Delta II rocket. On Feb. 16, NASA and its partners will launch the THEMIS mission, which is designed to detect magnetic storms. Image is courtesy of NASA/George Shelton. |

NASA will launch multiple satellites into Earth's orbit today, in a joint project with the Canadian Space Agency to understand the colorful aurora borealis and potentially disruptive magnetic storms in the atmosphere. Researchers plan to use the spacecraft to solve the mystery of how magnetic storms occur in order to better predict their dynamic behavior.

The mission is called Time History of Events and Macroscale Interactions

during Substorms, or THEMIS, and involves five satellites — the largest

number NASA has ever launched on a single rocket — that will line

up in orbit around Earth and connect with 20 observatories in Canada and

Alaska. This satellite array will be better able than a single satellite

to determine where magnetic storms begin.

There has never been such a systematic measurement system to record magnetic

storms in the atmosphere, says Xinlin Li of the University of Colorado

at Boulder, a co-investigator on the project. "These things happen

very fast" and the satellites must be lined up to catch the storms

in action, he says: "We're making our own space laboratory."

Magnetic storms often appear as the colorful aurora borealis. The 17th

century astronomer Galileo named the phenomena after the Roman goddess

of morning, thinking the luminescence was due to reflected sunlight in

the atmosphere. Astronomers now know, however, that it is not sunlight,

but solar wind, that powers the light show. The solar wind, a stream of

charged particles, flows around the planet, directed by Earth's magnetic

field.

Some of the particles, however, leak through the magnetosphere (the area around the planet where the magnetic field is located). When the particles interact with Earth's atmosphere, energy can be unpredictably released in what are called substorms, creating the light show we see in the northern skies. In fact, the aurora is simply a byproduct of Earth's dynamic magnetosphere, a 3-D manifestation of magnetic disturbances, says Larry Lyons of the department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences at the University of California at Los Angeles. But where exactly in the magnetic field these substorms begin and what physical processes drive them, are questions THEMIS strives to answer.

Toward that effort, THEMIS' dishwasher-sized satellites will align in orbit for 10 months, collecting measurements every four days and taking nearly 200 million photographs. The electrical discharges from THEMIS satellites will be timed with observations by the ground-based magnetometers — an array of 20 observatories from the eastern coast of Canada to the western coast of Alaska.

Understanding how, where and when these storms begin is important, as

not only do the sun's charged particles affect satellites in space, but

during very strong storms, the electricity can affect electronics on Earth.

Such substorms have been linked to disturbances to telecommunications

systems by knocking out satellites (see Geotimes,

October 2005). Measurements from THEMIS, however, might provide researchers

with the tools they need to predict such potentially disruptive events.

"Let's say you don't know anything about weather. If you want to

predict it, you can't just watch it change, you need to know the differences

between the storms and how they happen," Lyons says. THEMIS, he says,

will help.

Geotimes contributing writer

Links:

"Creating a formula for the Northern

Lights," Geotimes, February 2007

"Microsatellite

Mania," Geotimes, July 2006

"New

flare for space weather predictions," Geotimes, October

2005

THEMIS mission sites:

NASA

University

of California at Berkeley

Geological

Survey of Canada

University

of Calgary

Subscribe

Subscribe