|

FEATURE

Oil Around the World

Norway Looks North for Oil and Gas

Oil and Politics in Iraq

Squabbles over the South China Sea

Putting India on the World’s Petroleum Map

Oil Rushes Back to Libya

Norway Looks North for Oil and Gas

Allan Klo/StatoilHydro |

| The first tanker with a cargo of liquefied natural gas from the Snøhvit gas field left port in October 2007. |

Norway’s economy depends on the sea. Many tons of cod, herring, mackerel and other fish hauled in from Norwegian waters land on dinner plates around the world each year, making Norway the world’s second-largest fish exporter. Fifty years ago, no one would have predicted that another offshore resource — hydrocarbons — would one day supersede fish as Norway’s most valuable asset.

“The chances of finding coal, oil or sulfur on the continental shelf off the Norwegian coast can be discounted,” an official from the Norwegian Geological Survey wrote in a letter to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1958. The following year, however, a large gas field was discovered in the North Sea off the coast of the Netherlands, prompting speculation that similar deposits might lie a bit farther north. Exploration in Norwegian waters began in the early 1960s. By 1966, oil was discovered in the country’s first offshore well, and oil production began five years later in Norway’s first major oil field, Ekofisk. As of 2005, Norway was the world’s third-largest natural gas exporter and fifth-largest oil exporter. In 2006, these exports brought the country $94 billion — 15 times more than the value of fish exports, according to the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD).

After more than 35 years of oil and gas production on the Norwegian continental shelf, NPD estimates 65 percent of the region’s resources have yet to be tapped and a quarter have yet to be discovered. Current production and exploration activities are concentrated in the North Sea and Norwegian Sea. But oil and gas fields in these areas are maturing and production is beginning to decline. This has led companies to set their sights on Norway’s Arctic territory. “We expect one-third of future petroleum potential to be within the Barents Sea,” says geologist Bente Nyland, NPD’s director general. Compared to the heavily explored North Sea and Norwegian Sea, the Barents Sea is “virgin area,” and the last place left to find a major oil or gas discovery in Norway, she says.

Eiliv Leren/StatoilHydro |

| Natural gas from the Snøhvit gas field in the Barents Sea is delivered to this liquefied natural gas plant in northern Norway via an underwater pipeline. |

“Norway has been very, very careful in developing its oil and gas resources, managing them with a long-term view,” says Don Gautier, a geologist at the U.S. Geological Survey’s (USGS) Energy Resources Program in Menlo Park, Calif. And Arctic development is no different, he says. In addition to concerns over how gas and oil activities may affect Arctic wildlife, the Norwegian government is also concerned with how such activities may affect the region’s fishing industry, especially as nearly every resident’s livelihood is tied to fishing in Norway’s northernmost coastal villages, says Eldbjørg Vaage Melberg, an NPD spokesperson.

Within the Arctic Circle, Norway claims the northern and southern portions of the Barents Sea, but only certain areas are open for exploration and production. “The northern Barents Sea is currently closed and when and how to open it is under discussion,” Nyland says. The same is true for the southern portion of the Barents Sea that surrounds the Lofoten and Vesterålen islands off Norway’s northwestern coast. NPD is surveying the area to determine the environmental impacts of oil and gas drilling, Melberg says. Currently, only the southern Barents Sea is open for oil and gas activities.

Norway first opened the southern Barents Sea in 1980, but things have progressed sluggishly. “In the early days when the Barents Sea was opened in the 1980s, there was a lot of activity and discoveries made” Nyland says. “They were mainly gas, and it was impossible to produce because of the remoteness and distance to infrastructure,” she explains. This led to limited activity in the early 1990s followed by rising environmental concerns in the late 1990s that eventually led to the brief closure of the area. At the turn of the century, however, Norway re-opened the Arctic to oil and gas activities, Nyland says. Today, the area has one gas field and one oilfield ready for production.

Discovered in 1984, Snøhvit (“Snow White”) is Norway’s first gas field in the Arctic and one of the first offshore Arctic developments anywhere in the world, Gautier says. Gas production at Snøhvit began in fall 2007 thanks to technological improvement. “It’s quite remarkable because all of the technology is being installed subsea,” says Gautier, who traveled to Norway in December as a member of the USGS team that is assessing oil and gas resources in the Arctic. A 160-kilometer-long pipeline transports gas from Snøhvit’s seafloor platform to an onshore liquefied natural gas plant. In the future, gas may play a more prominent role than oil in Norway’s economy because the Barents Sea is expected to contain more gas than oil, Melberg says.

There is still one other Arctic area that Norway could develop: a 155,000-square-kilometer area of the Barents Sea currently claimed by both Norway and Russia. Because the two countries can’t agree on where to draw the boundary, however, they can’t develop the area. “As both Norway and Russia look to the Arctic for new oil and gas discoveries, the territorial dispute is taking on new importance because the area may be one of the most productive areas in the Barents Sea,” Gautier says. Although there are no test wells and few seismic lines in the disputed area, its geology is suggestive, he says. Nyland agrees: “The geology is the same on the Norwegian and Russian side,” she says. “There have been discoveries on both sides, so it’s tempting to expect such finds in the disputed area,” she adds. Despite the dispute, relations between the two countries are civil, Gautier says. And in 2007, Russia’s state-controlled Gazprom chose StatoilHydro, a Norwegian energy company, as a partner to develop its Shtokman gas field off Russia’s northern coast because of StatoilHydro’s technical skill in developing offshore fields in the Arctic.

This year may prove to be an active one for Norway’s Arctic. In addition to full-scale production at Snøhvit, the region’s first oilfield, Goliat, which was discovered in 2000, may soon go into production. The companies with licenses at Goliat, including StatoilHydro and Italy’s Eni, are expected to bring development plans before Norwegian authorities in early 2008, Melberg says. Over the next year, she says, the government also expects at least seven new exploration wells to open up in the southern Barents Sea.

Oil and Politics in Iraq

Copyright James Gordon |

| Oil production in Iraq, such as at Kirkuk, shown here, has stagnated at levels below what the country was producing before the U.S.-led invasion in 2003. |

Although oil prices have more than doubled in the five years since the United States invaded Iraq, that hasn’t translated into much more income for the beleaguered country. Security issues and the lack of a legally binding national oil policy have dogged Iraq for years and experts say they will continue to be a problem in the foreseeable future.

Iraq’s proven oil reserves top 115 billion barrels, with the potential for another 45 billion to 100 billion barrels of recoverable oil, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). The country hosts nine “super giants” — fields holding more than 5 billion barrels of oil — and 22 “giant” fields, which each have more than 1 billion barrels of oil. Yet thanks in part to three wars, and the combination of international sanctions and a government that opposed foreign investments — and the technological improvements they bring — over the past couple of decades, Iraq has the lowest reserve-to-production ratio of all major oil-producing countries. In fact, Iraq hosts the largest untapped reserves in the world, says James Paul, executive director of Global Policy Forum in New York. “It’s a pity, because at $95 a barrel, or $195 a barrel as [oil] may be in the near future, there’s a lot of money to be made,” says Gal Luft, executive director of the Institute for the Analysis of Global Security in Washington, D.C. “The net loss to the Iraqi economy and the Iraqi people is sad.” By the end of 2007, Iraq was averaging about 2.0 million barrels of oil per day (bpd) production, according to EIA, well below the 2.6 million bpd production before the U.S.-led invasion in 2003.

Iraq’s oil ministry aims to increase Iraq’s oil production to 6 million bpd by the end of this decade. To do so, the ministry says Iraq will need foreign investment of $25 million to $75 million in the oil sector. However, the security situation and the legal complications are such that that investment, at least from multinational oil companies, is unlikely in the near future, Luft says.

From April 2003 to May 2007, there were 400 individual attacks on Iraq’s oil infrastructure, according to EIA. Furthermore, roadside bombings, acts of sabotage and insurgent uprisings are rampant across Iraq. And now the Turkish government is sending troops into the Kurdistan region in northern Iraq to neutralize Kurdish forces. Because of this, “investors are sitting on their money,” Luft says. “There needs to be a sense that there is no back-sliding on security,” he says. “If international oil companies see that the region is moving toward greater security, they can say ‘things are looking rosier’ and can take baby steps toward investment.” Without a formal oil policy in place, however, multinational oil companies simply will not go into Iraq, Paul says.

Iraq’s Hydrocarbon Law — which is supposed to lay out the legal conditions for investment and international participation in Iraq’s oil and gas sector, including exactly how much control the companies have relative to the Iraqi government — is what everyone is waiting for, Paul says. The companies “want a legal status that can’t be changed” with every new administration or vote, he says. The Hydrocarbon Law was first presented to Iraq’s parliament on Feb. 27, 2007. As Geotimes went to press, it was still under considerable debate and unlikely to be passed anytime soon, given that some 70 percent of Iraqis are opposed to a law that gives control to anyone other than themselves, Paul says. Considering that the “Exxons of the world know it is better to wait until legality is established in Iraq,” the country is thus at an impasse, he says. And how to break this impasse is the “$64,000, or maybe $64 billion or trillion question,” he says. “Will the U.S. eventually be able to impose its will on Iraq? I don’t think we can say where this thing will end up,” he says.

Meanwhile, the Kurdistan Regional Government in northern Iraq is setting up its own oil exploration and production agreements, disregarding the central government’s vehement opposition to the move. While the big multinational oil companies are abstaining from getting involved, smaller international oil companies from Turkey, Canada, Norway, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, South Korea, China, Vietnam, Russia and other countries are setting up agreements with the Kurdistan government, says Naji Abdul-Rahman, a former oil engineer in Iraq. Despite threats from the central government that they will be “blacklisted” from further production and legal contracts once a national oil law is in place, these companies are going ahead with seismic and structural analyses and other exploration in the north, he says.

“The results are exciting,” says Mohammad Al-Gailani, managing director of GeoDesign Limited in the United Kingdom, whose company has been involved in evaluating prospects in northern Iraq. A handful of exploration wells have already revealed fields in which production could easily reach more than 100,000 bpd, he says. “Just the little work we’ve done so far has shown that the value of the whole reserves in Iraq is exponentially higher” than international estimates — which are based largely on decades-old seismic surveys, Al-Gailani says. Thus “high-risk fields,” such as those in the north, “become even more attractive to these smaller companies,” he says. Indeed, with oil prices as high as they are, some smaller companies are willing to take risks they might not have in the past, Abdul-Rahman says. Whether the central government’s threats will scare off potential investors remains to be seen, Luft says.

To get Iraq’s oil system to where it needs to be to help the Iraqi economy will be expensive and time-consuming, Luft says. A lot needs to be done to upgrade the infrastructure, he says: “Everything is very, very old and neglected.” Furthermore, he says, there is the question of what will happen if and/or when the United States and the United Kingdom withdraw from Iraq. “In the south, where most of the oil is produced, the big question is what will happen when the Brits withdraw,” Luft says. That could create a vacuum of power, which could lead to even more sabotage, oil theft and problems.

Squabbles over the South China Sea

Royal Dutch/Shell |

| Shell, like a few other companies, already has some ongoing exploration in the South China Sea, such as off the coast of Malaysia. |

Royal Dutch/Shell |

The South China Sea, stretching from Singapore to the Strait of Taiwan, includes hundreds of small islands and reefs. Although the islands are largely uninhabited, multiple nations have claimed them — historically, because of their strategic importance, but more recently, because of the potentially vast wealth of oil and gas on the seafloor surrounding them. But territorial disputes, technological risks and unsafe waters are making exploration of those resources less attractive to foreign investors than might be expected with global oil prices hovering near $100 per barrel.

As Asia’s rapidly growing economies call for increasing energy, exploring the region’s natural resources seems increasingly important. Oil consumption in developing countries in Asia will rise by 3 percent per year, on average, between now and 2025, with much of that increase coming from China, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

“The overall potential of the region has been known for some time,” says Don Juckett, former director of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG) Geoscience and Energy Office. However, he says, “some geophysical work has been done, but not much in terms of raw exploration.”

Technology has not been the issue: The geology of the region is relatively simple, consisting largely of buried carbonate reef complexes, and there’s very little of the South China Sea that could be considered ultra-deep, Juckett says. Instead, the delay in developing the South China Sea’s potential resources is caused largely by the territorial squabbles. Few companies will risk the capital when they don’t have a clear idea of what’s down there, he says — and they won’t bring the technology required to explore the area until there is a resolution of the territorial boundaries. In particular, the disputed Spratly Islands, a group of islands and reefs between the Philippines and Vietnam surrounded by potentially rich oil and gas deposits, are claimed by China, Taiwan, Vietnam, Malaysia and the Philippines.

Furthermore, Juckett says, the region is also notoriously unsafe: Modern pirates roam the well-traveled sea lanes in Southeast Asia and the Far East, armed with GPS and automatic weapons. “It’s considered a fairly high risk factor,” he says. Given the costs and risks, large oil and gas companies are likely to rank the region much lower on their portfolios, he says. As a result, it may be at least 10 years before production would begin, even if exploration began today with no barriers.

China, however, may see the situation differently. The South China Sea’s ocean floor is thought to have more natural gas than oil, and could potentially help supply China’s burgeoning natural gas market. Therefore, if anyone is likely to push forward on exploration in the region, it will be China, Juckett says. “The market is there, and it may be in its strategic interest to bring it online sooner,” he says. China’s imports of foreign oil and gas are at 4 million barrels a day, and rapidly growing. “Like the West-East pipeline, if they decide it’s in the interest of national security, they’ll get it done,” he says.

Uncertainty about where to find the resources is also holding international companies back, but one big discovery would likely bring the companies rushing forward, Juckett says. With that in mind, some countries have agreed to temporarily table their differences and begin exploration cooperatively — agreeing to sort out their territorial claims, and how to parcel whatever they find, at a later date.

One such cooperative project is a seismic survey that was recently conducted by China’s National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) with PetroVietnam and the Philippine National Oil Co.–Exploration Group. Results of that survey were “encouraging,” according to a spokesman for the Philippine corporation, as reported in Business World Online on Dec. 4. The survey was part of a 2005 agreement by the three nations to gather two- and three-dimensional seismic data over three years for a region west of the Philippines island of Palawan. A second phase of the survey, conducted aboard the Chinese vessel M/V Nan Hai 502, began in January 2008.

Meanwhile, some Western oil companies are at least dipping a toe in the region. In 2006, British Gas agreed to partner with CNOOC to conduct seismic surveys of two deepwater oil blocks in the western part of the South China Sea, and to drill one exploration well in each block.

India's Petroleum Numbers (2006) Print Exclusive

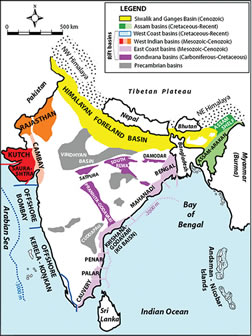

India is well-known for its historical civilization, diverse religions, enormous population, spicy food and tasty tea. But discoveries of significant oil and gas resources in recent years have placed the country in the spotlight of the petroleum industry — music to the ears of a nation with a rapidly growing economy.

India’s tea plantations and the discovery of its earliest oilfield are connected. When British explorers began to map the dense jungles of India’s northeastern Assam region in the 19th century, old reports from farmers of oil seepages in the area drew their attention. In 1865, the Geological Survey of India recommended drilling near some of these seepages. Only two years later, oil was struck in Assam. This was the first mechanically drilled and successful oil well in India, but it did not produce much. The commercial oil industry in India truly began in 1889, when, legend has it, an elephant working for the Assam Railways & Trading Company accidentally stepped into an oil seepage. “Dig! Boy!” cried the excited Englishman. The workers thus drilled the discovery, which is now the well-known Digboi oilfield.

Until the 1960s, India’s oil production was confined to Assam with a daily output of about 5,000 barrels. Then oil was discovered in western India, first in the onshore Cambay Basin in 1958 and later in the offshore Bombay Basin in 1974. These fields increased India’s daily production to 700,000 barrels.

For decades after India got its independence from Britain in 1947, the country maintained semi-socialist protectionist policies. The economy changed drastically, however, after Harvard-trained economist Manmohan Singh (India’s current prime minister) became the country’s finance minister in 1991 and the country entered the open international market, facilitating India’s rapid economic growth. The petroleum industry illustrates this economic evolution. For decades, the Indian government largely controlled the petroleum industry. Petroleum exploration and production (upstream activities) were left to the two nationalized companies Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC) and Oil India Ltd., while refining, distribution and marketing (downstream activities) were conducted by the Indian Oil, Bharat Petroleum and Hindustan Petroleum companies.

More recently, private and foreign oil companies have become active in India, most notably Reliance Industries (a private Indian company), Cairn Energy (Scottish), Nikko Resources (Canadian) and British Gas. In 1999, the Indian government introduced the New Exploration Licensing Policy under the Directorate General of Hydrocarbons, which allows all companies to bid for exploration blocks both on- and offshore India. So far, seven rounds of blocks have been awarded and an eighth is set to go on the market this spring.

Romesh Bhattacharji |

| A depiction of the first commercial production of oil in India in 1889 is exhibited in the Digboi Museum in Assam, India. |

Over the last decade, India’s economic liberalization coupled with the increased domestic and global demand for oil and advances in drilling technology in deepwater basins have changed the face of the petroleum industry in the country. This, in turn, has motivated new geologic appraisal of sedimentary basins in India.

More than 300 million years ago, India was part of the Gondwana supercontinent. India’s eastern margin was connected to East Antarctica and its western margin to Africa. The Tethys Ocean washed the northern shores of Gondwana. As the supercontinent began to break up, rift basins formed on India’s western and eastern margins. Some of these rift basins (called the Gondwana basins in India) contain abundant coal resources. About 130 million years ago, as India began to separate from Gondwana, the eastern and western margins of India became shallow sea and finally deepwater basins of the Indian Ocean. Around 50 million years ago, India began colliding with Asia, a tectonic event that sculpted the Himalayas. The Indus, Ganges and other rivers flowing out of the rising Himalayas filled the plains and basins in front of the rising mountains, and also transported considerable amounts of sediments to the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal. Current understanding of this geologic history has provided a new perspective for petroleum exploration in the country.

The recent discoveries in Assam demonstrate excellent potential for new oil reserves even in such a classic and mature petroleum province. Furthermore, petroleum discoveries offshore east India, which are very expensive ventures, were not made (as one may assume) by major international oil companies after extensive drilling, but by relatively small companies (notably Cairn Energy and Reliance Industries) that drilled a relatively small number of wells. The success rate of petroleum discoveries by Reliance Industries in deepwater basins offshore east India has been an impressive 80 percent. These discoveries include a series of gas fields named Dhirubhai, first made in the deepwater Krishna-Godavari Basin in 2002 through 2004 and extended to the deepwater Cauvery Basin in 2007. Last year, new oil and gas fields were found in the deepwater Krishna-Godavari Basin and ONGC announced the first discovery of gas fields offshore of the Mahanadi Basin. There is thus huge potential for future discoveries in these deepwater basins.

Additionally, the oil and gas discoveries in the onshore Rajasthan and Cambay basins indicate the extent to which many of India’s sedimentary basins have remained underexplored. Recent oil and gas discoveries in India are attracting major international companies to enter India's petroleum ventures.

India’s petroleum basins are showing great promise for new discoveries. At the same time, the country’s thirst for energy and fuel is rapidly increasing. India is the world’s fifth-largest energy consumer. Coal still dominates (57 percent), while oil accounts for 28 percent and natural gas supplies 8 percent of India’s energy consumption. India is the world’s sixth-largest oil consumer and imports three-quarters of its oil from overseas (mostly from the Middle East). Therefore, India itself will probably remain the sole buyer of the country’s oil and gas. Still, every step the country can take toward greater energy independence can add to its growing economy.

Oil Rushes Back to Libya

Copyright Carrie Teicher |

In 1985, foreign relations between Libya and the West had deteriorated so completely that Libyan leader Colonel Muammar al-Qaddafi expelled the United States and other Western countries, barring foreign access to its rich oil and gas fields. But after two decades of economic stagnation and outdated technology, Qaddafi began reopening the doors to foreign oil interests, offering new oil and gas exploration concessions — and the world has been eager to rush back in.

The domination of oil in Libya’s economy began in the 1950s, shortly after oil was first discovered in neighboring Algeria. By 1957, the first Libyan oil was struck, and by the mid-1960s, oil from the Sirte Basin, one of the largest oilfields in the world, was flowing, and international oil companies were actively seeking out new fields in the country, both onshore and offshore. After seizing power in 1969, however, Qaddafi nationalized Libyan oil operations in 1973, taking over 51 percent of the foreign oil companies still remaining in the country.

The last of the remaining foreign oil companies were cast out in the mid-1980s, following years of crumbling relations that culminated in the American bombing of Tripoli in 1986 and the Libyan attack on Pan Am Flight 103 that killed 270 people in 1988. Following the attack, the United States and many other Western countries declared Libya a state that sponsors terrorism and instituted economic sanctions.

Two decades of technological isolation and economic sanctions eroded Libya’s ability to produce and market its oil, however, and by 1999, Qaddafi had begun to reach out to the international economic community, agreeing to turn over two Libyan suspects in the Pan Am bombing. Following the World Trade Center attacks in September 2001, Qaddafi offered to help flush out the terrorists, and in return, Libya was omitted from President Bush’s “axis of evil.” American-Libyan relations continued to improve: Following the start of the Iraq War, Qaddafi renounced Libya’s programs to develop weapons of mass destruction, and by 2004, both the United Nations and the United States eased their embargos against the country.

Libya’s change of heart was economic, says David Curtiss, director of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists’ (AAPG) Geoscience and Energy Office. Additionally, Curtiss says, Qaddafi saw what had happened in Iraq, and decided to take a different route.

“Libya has the largest proven oil reserves in Africa, and they had not seen 20 years of technology,” Curtiss says. When Libya nationalized its oil operations, oil became the primary source of hard currency to the country, he says. Today, oil still comprises more than half of Libya’s gross domestic product. With new technologies and an enhanced understanding of geology, production could increase not only from existing oil fields, but also from largely unexplored, and potentially rich, fields.

Steffan Martikainen |

| Pictures abound of Libyan leader Colonel Muammar al-Qaddafi (shown here in an airport). His 2004 decision to halt Libya’s weapons of mass destruction program has led to Western energy companies coming back into the country. |

Once the embargo was lifted, the leaders of Libya’s National Oil Corp. began to meet with foreign oil company executives and announced the start of competitive bidding to explore and develop Libya’s oil and gas fields, which are still nationalized but would once again be open to the West for exploration. In January 2005, Libya announced that 11 of the 15 new oil and gas exploration concessions it was granting would go to U.S. oil companies, reestablishing the United States’ involvement in development and production in the country after a 20-year hiatus.

Most of Libya’s oil and gas activity is currently in the Sirte Basin, a province in the northern part of the country along the Mediterranean Sea that includes dozens of oilfields drilled into its Cretaceous sandstones and Eocene carbonates. But other onshore regions also hold promise, including the Murzuq Basin in the southwestern part of the country and the relatively unexplored regions of Kufra, to the southeast, and Cyrenaica, to the northeast. Potential exists offshore, too: In November 2007, ExxonMobil signed an exploration agreement for the offshore extension of the Sirte Basin.

Initially, however, much of the focus for foreign interests is likely to be on enhancing oil recovery in already producing fields, and on improving the surface infrastructure to transport the oil and gas.

“It’s breathtaking how many oil companies are active” in Libya now, Curtiss says. From the window of a major hotel in Tripoli, he says, “you can see the offices of 20 different companies. The capital is flowing.”

Subscribe

Subscribe