Geotimes

Untitled Document

Feature

Drawing Dinosaurs

Greg Paul

Humans are visual

beings. The data and analysis generated by scientific research are all well

and good, but people want to see what objects of research look like. That is

true whether the object is the structure of atoms, distant star systems or Mesozoic

dinosaurs — none of which can be depicted directly because they are too

remote in size, distance and time. The only way to see what cannot be recorded

is to restore its appearance by combining scientific information with artistic

interpretation.

Humans are visual

beings. The data and analysis generated by scientific research are all well

and good, but people want to see what objects of research look like. That is

true whether the object is the structure of atoms, distant star systems or Mesozoic

dinosaurs — none of which can be depicted directly because they are too

remote in size, distance and time. The only way to see what cannot be recorded

is to restore its appearance by combining scientific information with artistic

interpretation.

This scene showing Late Jurassic Apatosaurus

rearing on its hindlegs to feed high in a tree would have been considered outlandish

prior to the 1970s, when most restorations of such plant-eating dinosaurs indicated

they were semi-aquatic. Courtesy of Greg Paul.

In the world of dinosaur art, science plays a key role in informing artists

on the range of habitats, behavior and physical characteristics of the ancient

animals. But historically, the art has at times also informed the science, creating

a symbiotic relationship in which artists and scientists inspire one another

to higher levels of accuracy and artistic achievement.

Slugging around

The business of illustrating dinosaurs began in the early and middle 1800s,

soon after the first bones were identified in England (see story,

this issue). The initial attempts were way off the mark in terms of accuracy,

simply because the material available at the time was very fragmentary. Had

those early finds been complete skeletons, early restorations likely would have

been reasonably correct, as the art of illustrating animals was already fairly

well-developed and sophisticated.

As the 1800s progressed, people found more complete dinosaur skeletons, both

large and small. The illustrations of dinosaurs became correspondingly realistic

in basic form, producing the first icons of dinosaur imagery we are still familiar

with — Compsognathus, Iguanodon, Apatosaurus (more

familiarly known as Brontosaurus; see story sidebar,

this issue), Allosaurus and Stegosaurus. But while the gross design

and proportions of that early gallery of dinosaurs were pretty good, many important

aspects of the restorations were errant, and would remain so well into the 20th

century.

As further discoveries were made in the early 1900s, the gallery of well-known

dinosaurs ballooned. This was the Golden Age of classic dinosaur art, generated

in the studios of Rudolph Zallinger, Zdeneck Burian, William Scheele, John Germann,

Erwin Christman and above all Charles Knight. But with few exceptions, the dinosaur

images remained stuck in the 1800s, as they retained a set of characteristics

that solidified into a set of arbitrary conventions.

The fundamental reason for these early errors was the premise that dinosaurs

were fantastical Mesozoic reptiles. Because they were categorized as members

of Reptilia, dinosaurs presumably shared the chief characteristics found in

living turtles, lizards and crocodilians — including having low, reptilian

metabolic rates. Slow metabolisms not only hinder the control of body temperature,

but they also deprive an animal of the high aerobic exercise capacity that allows

birds and mammals to be frenetically active and energetic for long periods of

time, around the clock. Although many reptiles can produce bouts of intense

anaerobic-powered activity, they tire quickly, and most of the time they either

move slowly or not at all. Early paleontologists presumed that their Mesozoic

cousins were similarly inactive, and early artists usually portrayed them as

such.

The perception of general sluggishness in dinosaurs abounded in art prior to

the 1970s. Capturing a lack of movement is a subtle art, but several characteristics

highlight this trend.

Looking at the enormous body of dinosaur art produced for more than a century,

the peculiar fact emerges that in all but a few images, every single foot is

on terra firma. In illustrating all but the slowest pace for any moving animal,

however, at least one foot is always off the ground. Artists had long enjoyed

illustrating modern mammals as bounding over landscapes with feet — sometimes

all of them — clear off the ground, with galloping horses being a particular

favorite. Whether the near-phobia of showing active dinosaurs resulted from

artists having locked themselves into a convention or from paleontologists looking

over their shoulders, or both, is not known.

Other aspects of dinosaur movement were also erroneously modeled on reptiles.

The legs of most reptiles sprawl out to the sides, although crocodiles and chameleons

can adopt a more vertical, semi-erect pose. Placing the hindlegs of dinosaurs

far out to the sides was so contrary to the anatomy of their hip sockets that

few tried it, but the limbs of four-legged dinosaurs were still usually sprawled

laterally, sometimes to an extreme degree. Also, being a plodding lot, lizards

and crocs tend to drag their tails. Hence dinosaurs were chronically shown in

the 1960s doing the same — despite the lack of paleontological evidence.

Additionally, because they were seen as reptiles without much aerobic power

and also because they presumably did not have much in the way of brain power,

dinosaurs were usually shown as individualists. Scenes in which dinosaurs move

together in organized groups, or cared for their young, were scarce.

Then there were the scales. Many reptiles are scaly, so dinosaurs were portrayed

that way too. Although no scales were found associated with small dinosaurs,

skin impressions showed that a variety of large dinosaurs were covered by mosaic

patterns of scales. The notion that some dinosaurs were feathered may well have

not occurred to anyone, as birds were thought to have nothing to do with the

group.

In keeping with this conservatism, dinosaurs were almost invariably restored

as drab in color. Doing something exciting with the beasts was just beyond the

pale. In one of the oddest conventions, bird-footed predatory dinosaurs were

portrayed as being hydrophobic, even though their long toes were fairly well-suited

for traversing soft sand in water, as they are in modern birds. The short-toed

sauropods and duckbilled hadrosaurs, seen as waterloving herbivores, supposedly

retreated to deep water to escape their tormentors.

The fact is that for decades, little science was supporting dinosaur paleontology,

which was then largely a descriptive field practiced by a handful of researchers

who did little to test the prevailing assumptions. The classic look was never

based on sound research; indeed, it was often contradicted by obvious evidence.

There were some exceptions, however.

At Dinosaur National Monument, for example, wildlife artist Bill Berry did some

marvelous small-scale color studies that were anatomically superior to previous

efforts, although he retained the classic style. His snorkeling Diplodocus

pair is the most evocative such portrayal ever achieved. And his horizontal-bodied

Allosaurus pursuing Camptosaurus into the water is fully modern.

As the decade closed, the spirit of the age began to catch up with the Mesozoic

beasts, with paleontologists John Ostrom and Robert Bakker starting to contend

that dinosaurs were not reptilian in their energy levels, and that birds were

the direct descendents of bipedal meat-eating dinosaurs called theropods.

Energetic revival

Bakker’s

involvement was especially critical in that he was an artist who translated

the new paleontological ideas directly into dramatic illustrations that overturned

all that had gone before. He took Ostrom’s bird-like Deinonychus

and had it running full tilt, one leg tucked up like a chicken. Most audacious

of all, the Chasmosaurus pair — rhino-like horned dinosaurs at full

gallop on completely erect legs toward the viewer, great frills tilted up —

looked like horses in a Remington Western piece.

Bakker’s

involvement was especially critical in that he was an artist who translated

the new paleontological ideas directly into dramatic illustrations that overturned

all that had gone before. He took Ostrom’s bird-like Deinonychus

and had it running full tilt, one leg tucked up like a chicken. Most audacious

of all, the Chasmosaurus pair — rhino-like horned dinosaurs at full

gallop on completely erect legs toward the viewer, great frills tilted up —

looked like horses in a Remington Western piece.

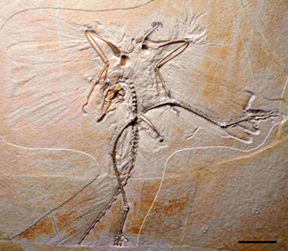

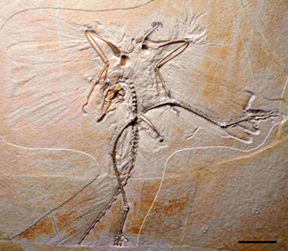

The first feathered dinosaur restoration

ever published, this illustration by Sarah Landry of Early Jurassic Syntarsus

chasing a gliding lizard appeared in Scientific American in 1975. Courtesy

of Sarah Landry.

Still, as the 1970s opened, the new dinosaur art did not immediately take off.

A breakthrough, however, came in Bakker’s seminal 1975 Scientific American

article “Dinosaur Renaissance.” Ironically, the essay included only

one dinosaur illustration, but it was groundbreaking. Executed by one of the

periodical’s regulars, Sarah Landry did what (as far as I know) no one

had before: applied feathers to a dinosaur, the little African Syntarsus,

which was shown dashing down a dune slope like a long-tailed bird (see image).

As dinosaur science became both more interesting and scientific, a snowball

effect occurred in which an increasing number of researchers produced a larger

body of discoveries and analytical results, spurring greater popular interest,

and in turn more scientific effort. Freed from the constraints of the classic

conventions, and with growing public demand for illustrations of the new view

of dinosaurs, a community of young dinosaur artists appeared and began to expand

with increasing rapidity in the late 1970s and 1980s.

Living in an age of rapid communication, they soon formed the first, loose community

of paleoartists, differing from prior generations that worked individually in

isolation. In a virtual slap in the face of the old ways, this new generation

showed swimming theropods attacking terrestrial sauropods that had been foolish

enough to retreat to the water. And based on analysis of skeletal organization

and habitat, the duckbilled hadrosaurs were portrayed as gently caring for their

nestlings.

The fossil evidence backing parental care included newly discovered nesting

grounds, with juveniles well past hatchling size still in the open pit nests.

More recently, skeletons of some of the most bird-like dinosaurs have been found

still in the brooding position in which they died, atop double-layer rings of

eggs that were half buried in the soil — a pre-avian form of nesting. Because

numerous parallel trackways and single-species bonebeds suggest herding behavior,

the small-brained dinosaurs are often shown moving in large groups (see story,

this issue). Such work by many paleobiologists supported high-energy levels

for dinosaurs and motivated paleoartists to create restorations of energized

dinosaurs.

Continued challenges

Although based on much better science than the poorly founded classic view,

the new look in dinosaur art and restoration has provoked both controversy and

occasional excess. Hotly debated, for example, is the running ability of gigantic

theropods (such as Tyrannosaurus rex) and ceratopsids (such as Triceratops).

Even assuming, as the anatomical evidence suggests, that some giant dinosaurs

could run much faster than equally large elephants, it was not physically possible

for them to cavort and bounce about like oversized gazelles, as some over-enthusiastic

artists are fond of illustrating and sculpting them.

The questions of whether some sauropods could rear up or not and whether it

was possible for them to raise their heads far above the level of their hearts,

which had to pump blood up, also have not been settled. Portrayals of ceratopsids

deployed in defensive rings around their young are not supported by any fossil

evidence, and such sophisticated habits are rare among modern ungulates and

may have been beyond the limited mental capacities of the reptilian-brained

dinosaurs. It is also unlikely, based on the fossil record, that dinosaurs lavished

their young with the intense parental care seen in many birds and mammals.

In accordance with the probability that dinosaurs had color vision as do reptiles

and birds, today’s artists frequently adorn their creations with bright

colors and bold patterns. In both cases, these more visually appealing schemes

are as speculative as they are plausible; as we usually have no means of determining

color, it is acceptable to take some artistic license. But this brings us to

one of the most extraordinary events in dinosaur art: feathers.

New finds of preserved skin impressions have greatly expanded our knowledge

of the body coverings of dinosaurs, but that is not the remarkable thing. Well

into the 1990s, most artists continued to cover small dinosaurs, including the

little theropods, with scales. A few, including myself, opted for feathers because

of the predatory dinosaurs’ close relationship to birds, and the high level

of heat production they probably enjoyed.

In the mid-1990s, the first small theropods with a soft, bristly body covering

were discovered in fine-grained deposits in northeastern China. The first specimens

were not especially well-preserved, but the deposits are extensive and more

specimens were bound to turn up. Now a panoply of feathered theropods is known

from China. In at least one specimen, the tail feathers show a clear pattern

of pigment banding, although the original colors are lost. A stunning discovery

was of small dromaeosaur theropods with fully developed wings not only on their

arms, but also on their hindlegs, producing a bipedal flying form dramatically

unlike anything living today.

Into the mainstream

Not a single dinosaur documentary aired on TV in the 1960s — a short segment

of badly executed stop-motion animation at the beginning of a National Geographic

special on reptiles being a poor substitute. But the media has undergone a boom

in dinosaur art in the past couple of decades, with museums adding and upgrading

evermore well-liked dinosaur exhibits, and books and documentaries on the subject

becoming numerous.

This trend went high-tech in the 1980s, when companies started producing full-

and near-scale robotic dinosaurs, often set within ancient habitats. Sound in

concept and initially fashionable with the public, the execution of these machines

has not always been what one might hope for. At the same time, full dinosaur

documentaries became adorned by sophisticated animation.

In 1993, Jurassic Park became the first blockbuster film to feature modern

dinosaurs, animated with computers and robotics. The movie industry has not,

however, generated substantial work for paleoartists because studios prefer

to fictionalize dinocharacters for copyright and entertainment purposes, and

they tend to use in-house talent over which they have more control over. Even

so, Jurassic Park was like throwing gasoline on the fire.

Today, so many artists around the world illustrate dinosaurs that they cannot

be readily listed. With the proliferation of cable channels, documentaries featuring

computer-generated animation have become as common as they are widely watched

(see Geotimes, June 2005). These productions have

received some criticism for over-simplifying the science of paleontology and

for not always meeting the highest technical standards of paleoart.

Meanwhile, formal dinosaur restoration is becoming increasingly technological

as it undergoes a shift to digital media. Virtual 3-D technologies are assisting

in restoring dinosaurs at the fundamental skeletal and functional level. However,

it remains true that high-tech restorations do not always conform to what real,

living animals can do.

For example, scientists commonly presume that animals do not rotate joints beyond

the limits indicated by the maximum extent of their articulations. But in fact,

many animals regularly disarticulate joints during normal movements, an example

of which is the disassembly of the wrist of the horse during the gallop. Giraffes

and camels can touch their backs and flanks with their heads, even though the

neck articulations do not seem to allow such motion.

There is always the danger of excessive conservatism when it comes to estimating

what animals can do. If marine mammals were extinct, would they be restored

as being able to dive to extreme depths for long periods of time, when normal

mammal respiro-circulatory systems cannot achieve such incredible performance?

The need remains to more thoroughly examine the form and actual function of

living animals, to better understand those of fossil forms.

As far as the science of paleoart has come, it has a long way to go. But considering

that dinosaur paleontology is continuing to thrive and expand, and that fascination

with dinosaurs is growing around an increasingly educated globe, the future

of dinosaur art in the new century looks promising.

An independent researcher,

Paul is author of Dinosaurs of the Air (Johns Hopkins University Press)

and editor of The Scientific American Book of the Dinosaur. In addition

to illustrating dinosaurs, he researches various aspects of their biology and

evolution.

Links:

"The Three Faces of Dinosaurs,"

Geotimes, January 2006.

"The dinosaur formerly known

as...," Geotimes, January 2006.

"On the Trail of Dinosaurs," Geotimes,

January 2006.

"Bringing Dinosaurs to Life,"

Geotimes, June 2005.

Back to top

Untitled Document

Humans are visual

beings. The data and analysis generated by scientific research are all well

and good, but people want to see what objects of research look like. That is

true whether the object is the structure of atoms, distant star systems or Mesozoic

dinosaurs — none of which can be depicted directly because they are too

remote in size, distance and time. The only way to see what cannot be recorded

is to restore its appearance by combining scientific information with artistic

interpretation.

Humans are visual

beings. The data and analysis generated by scientific research are all well

and good, but people want to see what objects of research look like. That is

true whether the object is the structure of atoms, distant star systems or Mesozoic

dinosaurs — none of which can be depicted directly because they are too

remote in size, distance and time. The only way to see what cannot be recorded

is to restore its appearance by combining scientific information with artistic

interpretation.

Bakker’s

involvement was especially critical in that he was an artist who translated

the new paleontological ideas directly into dramatic illustrations that overturned

all that had gone before. He took Ostrom’s bird-like Deinonychus

and had it running full tilt, one leg tucked up like a chicken. Most audacious

of all, the Chasmosaurus pair — rhino-like horned dinosaurs at full

gallop on completely erect legs toward the viewer, great frills tilted up —

looked like horses in a Remington Western piece.

Bakker’s

involvement was especially critical in that he was an artist who translated

the new paleontological ideas directly into dramatic illustrations that overturned

all that had gone before. He took Ostrom’s bird-like Deinonychus

and had it running full tilt, one leg tucked up like a chicken. Most audacious

of all, the Chasmosaurus pair — rhino-like horned dinosaurs at full

gallop on completely erect legs toward the viewer, great frills tilted up —

looked like horses in a Remington Western piece.