Geotimes

Untitled Document

Feature

The Three Faces

of Dinosaurs

Spencer G. Lucas

First named dinosaur Print

Exclusive

The dinosaur formerly known as…

Lizard-like brutes, reptiles or birds - during the past 200 years, paleontologists

have developed radically different images of dinosaurs. The three images of

dinosaurs tell a remarkable story of how paleontological discoveries have driven

research that has shaped and reshaped paleontologists' understanding of of the

most famous of all extinct creatures.

Dinosaurs as lizards

The

scientific study of dinosaurs began in England during the 1820s, when British

geologist and naturalist William Buckland published the first scientific description

of a dinosaur. In 1824, Buckland coined the name Megalosaurus (“big

lizard”) for a huge jaw with dagger-like teeth found in Jurassic rocks

in Stonesfield (see sidebar). Gideon Mantell, an English

country doctor whose avocation was paleontology, had actually discovered dinosaur

teeth and bones in Lower Cretaceous rocks in the Weald region of southern England

two years earlier, but did not publish his discovery until 1825. He named these

fossils Iguanodon (“iguana tooth”) because they included teeth

that resembled those of a living iguana.

The

scientific study of dinosaurs began in England during the 1820s, when British

geologist and naturalist William Buckland published the first scientific description

of a dinosaur. In 1824, Buckland coined the name Megalosaurus (“big

lizard”) for a huge jaw with dagger-like teeth found in Jurassic rocks

in Stonesfield (see sidebar). Gideon Mantell, an English

country doctor whose avocation was paleontology, had actually discovered dinosaur

teeth and bones in Lower Cretaceous rocks in the Weald region of southern England

two years earlier, but did not publish his discovery until 1825. He named these

fossils Iguanodon (“iguana tooth”) because they included teeth

that resembled those of a living iguana.

This life-sized sculpture of Iguanodon

— one of the earliest dinosaur fossils discovered — completed by Benjamin

Waterhouse Hawkins in 1854, still stands in London. Note the ponderous, lizard-like

appearance of the dinosaur and the spike (horn) on the nose, characteristics

that were typical of early understandings of dinosaurs. Later, scientists learned

the dinosaur was more like a kangaroo, and the spike was on the thumb. Image

courtesy of Robert M. Sullivan.

The 1830s saw additional dinosaur bones, which were discovered in England and

received names such as Hylaeosaurus (“Wealden lizard”), Cetiosaurus

(“whale-like lizard”), Poekilopleuron (“mottled rib”)

and Thecodontosaurus (“socket-toothed lizard”). These first

dinosaurs, however, were not called dinosaurs; paleontologists of the time saw

them as giant, lizard-like reptiles.

For example, Mantell estimated Iguanodon’s size by simply scaling

up a modern iguana to produce a 25-meter-long giant. (Later knowledge of complete

skeletons of Iguanodon would reveal that it was only 8 to 9 meters long.)

Of course, all the discovered dinosaur fragments from the 1830s resembled the

bones and teeth of living lizards (and crocodiles), so the image of dinosaurs

as gargantuan lizards was well-founded at the time.

In 1841, British paleontologist Richard Owen boldly united many of these giant

lizards into a new group of reptiles, the dinosaurs, literally meaning “terrible

lizards.” Owen brought a much broader and deeper knowledge of comparative

anatomy to the study of dinosaurs than had Buckland or Mantell. But while Owen

stressed the mammal-like limb posture of dinosaurs, he did not doubt their lizard-like

attributes.

In the 1850s, Owen collaborated with artist and sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse

Hawkins, producing both paintings and, more notably, a set of life-sized sculptures

of dinosaurs for the grounds of the Crystal Palace exhibition in London, where

they still stand. These sculptures, completed in 1854, brought the dinosaurs

to life as huge, lizard-like brutes — establishing their first scientific

image.

Dinosaurs as reptiles

In 1855, dinosaur teeth discovered in North America, in the distant territory

that is now Montana, captured the attention of Joseph Leidy, a Philadelphia

anatomist, inspiring him to study vertebrate paleontology. Soon thereafter,

in 1858, a nearly complete skeleton of a dinosaur came out of a rock pit near

Haddonfield, N.J. Leidy christened it Hadrosaurus (“heavy lizard”)

and studied its complete forelimbs and hindlimbs to reconstruct the dinosaur

as an upright biped, unlike the ponderous quadrupeds of the Owen-Hawkins sculptures.

Still, more complete dinosaur skeletons were necessary to remake the dinosaurs’

image.

After the American Civil War, during the 1870s and 1880s, two ambitious rivals,

independently wealthy Edward Drinker Cope of Philadelphia and Yale College professor

Othniel Charles Marsh of New Haven, dominated American paleontology. Collectors

in the employ of these savants discovered dinosaur fossils across western North

America, shipping back many skeletons of bizarre dinosaurs totally new to science,

such as Stegosaurus (“plated lizard”), Triceratops (“three-horned

face”) and Brontosaurus (“thunder lizard,” now called

Apatosaurus, “deceitful lizard”; see sidebar).

Marsh’s skeletal reconstructions were particularly significant because

they were the first published images of complete dinosaur skeletons. Cope, however,

speculated more widely than Marsh did on dinosaur lifestyles — first conceiving

of active, fighting dinosaurs and formulating the notion (now rejected) that

sauropods (plant-eaters) used their long necks as snorkels while ambling across

lake bottoms. At the same time as the discoveries rolled in from the American

West, complete dinosaur skeletons were found in Europe, notably the 1878 unearthing

of exquisite skeletons of Iguanodon in a coal mine at Bernissart, Belgium.

The newly discovered complete skeletons of dinosaurs forced a makeover of the

Owen-Hawkins image of dinosaurs. One particularly interesting revelation concerned

the bony spike that was among the first fragmentary bones of Iguanodon discovered:

Mantell and Owen had both identified the spike as a horn on the tip of the dinosaur’s

nose, but the complete Iguanodon skeletons from Bernissart revealed it to be

a thumb spike.

Dinosaurs emerged as unique reptiles, walking on upright limbs and totally unlike

any living lizard in overall shape and appearance. Still, dinosaurs’ generally

gigantic size and obvious reptilian affinities (particularly their close relationship

to living crocodiles) heavily colored conclusions about dinosaurian biology.

Paleontologists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries perceived dinosaurs

as ponderous, slow, coldblooded and dimwitted. They also realized that dinosaurs

were extinct, having disappeared at the end of the Cretaceous period 65 million

years ago, leading to the second dictionary definition of a dinosaur as something

unwieldy, outmoded or unable to adapt to change.

The best images of this perception of dinosaurs as reptiles came from another

paleontologist-artist collaboration between Henry Fairfield Osborn, the American

Museum of Natural History’s premier paleontologist and a protégé

of Cope, and Charles Knight, a remarkably talented painter and sculptor (see

story, this issue). Knight’s images portrayed unique

but reptilian dinosaurs, such as can be seen in his classic painting of a confrontation

between Triceratops and Tyrannosaurus. These images were so influential that

they pervaded dinosaur art for more than half a century and shaped the work

of many artists. To this day, Knight’s paintings of dinosaurs remain some

of the most familiar and copied images of dinosaurs. Indeed, the first Hollywood

dinosaurs, including those felled by King Kong in his 1933 movie debut, came

straight out of Knight’s paintings.

Dinosaurs as birds

It

is fair to say that the paleontological image of dinosaurs as reptiles, well-established

by the 1920s, changed little from the 1920s until the 1970s; dinosaur science

was no longer a forefront of paleontological research. Those who did study dinosaurs

continued to work within the framework of dinosaurs as strange and unique reptiles,

but still as biologically reptilian. Researchers in the 1970s changed this trend,

beginning a makeover of the dinosaurs’ image that continues today. The

new image of dinosaurs strongly allies them both evolutionarily and biologically

more to birds than to reptiles.

It

is fair to say that the paleontological image of dinosaurs as reptiles, well-established

by the 1920s, changed little from the 1920s until the 1970s; dinosaur science

was no longer a forefront of paleontological research. Those who did study dinosaurs

continued to work within the framework of dinosaurs as strange and unique reptiles,

but still as biologically reptilian. Researchers in the 1970s changed this trend,

beginning a makeover of the dinosaurs’ image that continues today. The

new image of dinosaurs strongly allies them both evolutionarily and biologically

more to birds than to reptiles.

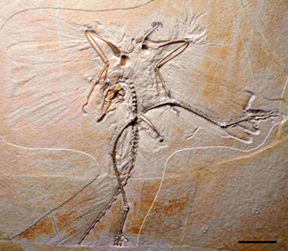

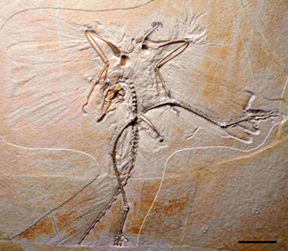

This skeleton with wing and tail feather

impressions is the 10th specimen of the first known bird, Archaeopteryx.

The new specimen provides important details on the feet and skull of these birds

and strengthens the widely accepted argument that modern birds arose from theropod

(meat-eating) dinosaurs. Image courtesy of G. Mayr/Senckenberg; Science.

Most paleontologists now point to the work of Yale paleontologist John Ostrom,

who passed away last year, as the key to this makeover. In the 1960s, Ostrom

had begun to question in print the notion of dinosaurs being slow and ponderous.

Particularly significant was his monographic analysis in 1969 of a striking,

new kind of meat-eating dinosaur, Deinonychus (“terrible claw”)

from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana. This 3-meter-long (10-foot) biped has

a fierce, 10-centimeter-long (4-inch) claw on each hind foot, slender and hollow

limb bones, and bony tendons that held its tail out as a rigid counterbalance

to its body. Ostrom described it as “an active and very agile predator”

with a metabolism more akin to that of a modern bird or mammal than to a lizard.

In the 1970s, Ostrom also revived the idea (first suggested by Charles Darwin’s

great supporter Thomas Henry Huxley in 1868) that birds descended from dinosaurs.

He did so by making a compelling case that the oldest bird, the 150-million-year-old

Archaeopteryx from the Jurassic in Germany, was little more than a meat-eating

dinosaur with feathers. Ostrom thus reasoned that if birds are highly active

and warmblooded, so too were their immediate ancestors among the dinosaurs.

In 1975, one of Ostrom’s students, Robert Bakker, published a provocative

article in Scientific American, asserting that all dinosaurs were warmblooded

(endothermic), and the “dinosaur renaissance” (as Bakker aptly titled

his article) had begun.

The dinosaur renaissance continues today, with more scientific attention lavished

on dinosaurs than on any other group of fossil vertebrates, with the possible

exception of the fossil hominids central to understanding human evolution. Bakker’s

1975 article and others that followed sparked a lively debate about dinosaur

metabolism that forced a reevaluation of long-cherished notions about the terrible

lizards.

Compelling evidence from new kinds of analyses, such as histology — the

study of microscopic structure of dinosaur bone — challenged old ideas

about dinosaurian metabolism and activity levels. Ostrom, for example, estimated

dinosaurian blood pressures (using the vertical distance between the heart and

the brain as a proxy, which suggested some very high dinosaurian blood pressures)

and reviewed where dinosaurs lived (they even extended into the poleward regions

of the globe) to argue for some degree of dinosaur warmbloodedness.

The current consensus is that many dinosaurs (especially the small meat-eaters)

had a metabolism akin to warmblooded mammals and birds, whereas others (the

giant sauropods) were coldblooded behemoths whose gargantuan size guaranteed

a nearly constant body temperature. To understand this range, we would do well

to remember the variety of dinosaurian body sizes, from agile, chicken-sized

predators to school bus-sized (and larger) herbivores. Much as living mammals

— from tiny shrews to blue whales — display a range of metabolic activity

determined in part by body size, dinosaurs employed a range of metabolic strategies.

Dinosaur posture and locomotion have also proved lively areas of discussion.

Dinosaur footprints, long regarded as curiosities, now hold center stage as

the best prima facie evidence of how dinosaurs walked (see story,

this issue). They also provide the soundest basis for estimating dinosaur walking

and running speeds. Analyses of dinosaur footprints supports the upright walking

postures long inferred from skeletal evidence, but indicates rather slow to

moderate walking speeds (5 to 8 kilometers per hour) for the average dinosaur.

Prancing sauropods and galloping stegosaurs seem to be the excesses, not the

well-established inferences, of the dinosaur renaissance.

The relationship of dinosaurs to birds looms large in current paleontological

thinking about dinosaurs. Crocodiles are the closest reptilian relatives of

dinosaurs, a conclusion well-accepted since the 1800s. But this relationship

is a relatively distant one, like that of cousins. By contrast, the dinosaur-bird

relationship is that of ancestor and descendent, a much closer relationship

analogous to that between parent and child.

Paleontologists are almost unanimous in their agreement that the dinosaur-bird

relationship mandates a more bird-like biology of dinosaurs than previously

thought, and recent discoveries support that inference. For example, we now

know that the furcula, or “wishbone,” which is the fused collarbones

long thought to be unique to the avian skeleton, was present in several kinds

of meat-eating dinosaurs, including the legendary Tyrannosaurus rex.

And from 125-million-year-old Lower Cretaceous lake beds of northeastern China

have come Caudipteryx (“tail wing”) and other small meat-eating

dinosaurs sheathed in feathers. Indeed, new discoveries have truly blurred the

distinction between dinosaurs and birds.

Refining the view

The story of the different images of the dinosaurs — as lizards, reptiles

and birds — is a tale rooted in the discovery of new fossils. Although

new kinds of analyses, such as bone histology, have also provided modern paleontology

with novel insights not previously available, the discovery of new fossils drives

paleontology. It was the discovery of complete dinosaur skeletons during the

1870s and 1880s that revised the Owen-Hawkins images of dinosaurs as lizards.

Beginning in the 1960s, the discovery of Deinonychus and other bird-like

dinosaurs drove acceptance of the dinosaur-bird link that proved to be pivotal

to the current image of bird-like dinosaurs.

The current rapid pace of dinosaur discovery and research continues to sharpen

this image of bird-like dinosaurs. Recent discoveries in Africa revealed bizarre

new dinosaurs that are shaking the evolutionary tree so long accepted by paleontologists.

And in 2003, Chinese paleontologists described Microraptor, a small (77-centimeter-long)

meat-eating dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous lake beds of northeastern China.

Covered with feathers, Microraptor was an arboreal glider that well represents

the evolutionary intermediate (“missing link”) between a ground-running,

meat-eating dinosaur and its descendants, the earliest birds.

Through all this, the reptilian nature of some key aspects of dinosaur biology

has been upheld. For example, dinosaurs reproduced by laying eggs and most had

naked, scaly skins like those of living reptiles. Yet the dinosaur-bird link

has forced a serious rethinking of much of dinosaurian biology and appearance

that now pervades our current image of the terrible lizards.

And ongoing research on baby dinosaurs, and particularly on how and at what

rate dinosaurs grew, promises a more profound understanding of dinosaur biology.

Dinosaurs thus continue to be one of the hottest areas of paleontological research.

|

The dinosaur formerly known

as…

Paleontologists who discover new dinosaurs also name them. A set of rules,

the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, governs the scientific names

given to dinosaurs (and to all animals). These rules promote the consistency

and stability of scientific names. They thus mandate that all names be in Latin

and that the first name correctly proposed for an animal takes priority over

subsequently proposed names. The history of Brontosaurus — one of

the most familiar of dinosaur names — provides a classic example of the

code in action.

In 1877, Yale paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh coined the name Apatosaurus

(“deceptive lizard”) for bones of a sauropod dinosaur from the

Jurassic of Colorado. In 1879, Marsh thought he had a different kind of

sauropod, proposing the name Brontosaurus (“thunder lizard”)

for a nearly complete skeleton from the Jurassic of Wyoming. The colorfully

named Brontosaurus became one of the dinosaurs best known to the

public.

Subsequent research, however, demonstrated that Apatosaurus and Brontosaurus

are two names for the same kind of dinosaur. Therefore, the code dictates that

the uninspired Apatosaurus has priority over Brontosaurus.

All school children are now happy to correct an errant adult who dares use Brontosaurus,

but the name is so well entrenched that the U.S. Postal Service used it on a

stamp issued in the 1980s. Apatosaurus may be technically correct, but Brontosaurus

endures, as does the term “brontosaur” as a vernacular for sauropod.

Perhaps the best way to reconcile this is to regard Brontosaurus as the

“stage name” of the dinosaur correctly called Apatosaurus,

and use both accordingly.

SGL

|

Lucas is curator of paleontology

and geology at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History. E-mail: spencer.lucas@state.nm.us.

Links:

"Drawing Dinosaurs," Geotimes, January 2006. Print

Exclusive

"On the Trail of Dinosaurs," Geotimes, January 2006. Print

Exclusive

Back to top

Untitled Document

The

scientific study of dinosaurs began in England during the 1820s, when British

geologist and naturalist William Buckland published the first scientific description

of a dinosaur. In 1824, Buckland coined the name Megalosaurus (“big

lizard”) for a huge jaw with dagger-like teeth found in Jurassic rocks

in Stonesfield (see sidebar). Gideon Mantell, an English

country doctor whose avocation was paleontology, had actually discovered dinosaur

teeth and bones in Lower Cretaceous rocks in the Weald region of southern England

two years earlier, but did not publish his discovery until 1825. He named these

fossils Iguanodon (“iguana tooth”) because they included teeth

that resembled those of a living iguana.

The

scientific study of dinosaurs began in England during the 1820s, when British

geologist and naturalist William Buckland published the first scientific description

of a dinosaur. In 1824, Buckland coined the name Megalosaurus (“big

lizard”) for a huge jaw with dagger-like teeth found in Jurassic rocks

in Stonesfield (see sidebar). Gideon Mantell, an English

country doctor whose avocation was paleontology, had actually discovered dinosaur

teeth and bones in Lower Cretaceous rocks in the Weald region of southern England

two years earlier, but did not publish his discovery until 1825. He named these

fossils Iguanodon (“iguana tooth”) because they included teeth

that resembled those of a living iguana.

It

is fair to say that the paleontological image of dinosaurs as reptiles, well-established

by the 1920s, changed little from the 1920s until the 1970s; dinosaur science

was no longer a forefront of paleontological research. Those who did study dinosaurs

continued to work within the framework of dinosaurs as strange and unique reptiles,

but still as biologically reptilian. Researchers in the 1970s changed this trend,

beginning a makeover of the dinosaurs’ image that continues today. The

new image of dinosaurs strongly allies them both evolutionarily and biologically

more to birds than to reptiles.

It

is fair to say that the paleontological image of dinosaurs as reptiles, well-established

by the 1920s, changed little from the 1920s until the 1970s; dinosaur science

was no longer a forefront of paleontological research. Those who did study dinosaurs

continued to work within the framework of dinosaurs as strange and unique reptiles,

but still as biologically reptilian. Researchers in the 1970s changed this trend,

beginning a makeover of the dinosaurs’ image that continues today. The

new image of dinosaurs strongly allies them both evolutionarily and biologically

more to birds than to reptiles.