|

GEOMEDIA

Check out the latest On the Web links, your connection to earth science friendly Web sites. The popular Geomedia feature is now available by topic.

Museums: A Fresh Look at Dinosaurs in Their Time

Books: Soil Can Bring Down Society: A Review of Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations

A Fresh Look at Dinosaurs in Their Time

Carnegie Museum of Natural History |

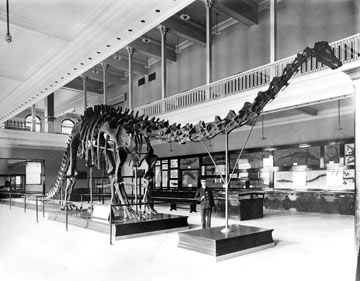

| The Carnegie Museum of Natural History used to display their dinosaurs like this Diplodocus in static, inaccurate poses. |

Towering over an infant who is not much taller than the surrounding ground ferns, a mother Apatosaurus arches her neck to get a good look at the ravenous Allosaurus approaching from behind with an eye fixed on the young one. Swinging her tail in an effort to bring down the quick predator, the Apatosaurus spies another Allosaurus in the distance coming to serve as reinforcement in the attack. A stoic Stegosaurus, armed with a row of plates down its back and a spiked tail, watches impassively from the sidelines while a Diplodocus flees and a slight meter-tall Camptosaurus hides among the groundcover under a tall ginkgo tree.

It’s just a typical day in the Late Jurassic of western North America, a scene that paleontologists at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Natural History recreated with fossilized skeletons in the museum’s newly renovated dinosaur exhibition, Dinosaurs in Their Time, which opened Nov. 21. For the past few years, the Carnegie Museum has been updating and expanding the old dinosaur hall to improve its scientific accuracy and building life-size exhibits filled with fossils, artificial vegetation, reconstructed animals and elaborate murals that depict life in the Mesozoic Era — all in an effort to place the dinosaurs in the larger context of their ancient environments, allowing them to mingle with other creatures that lived during the Age of Dinosaurs.

“We really wanted to take these fossils that before were standing on unadorned platforms … and put them in accurate reconstructions of their environments,” says Carnegie paleontologist Matt Lamanna, lead scientific advisor for the renovation. “If you imagine flesh on the bones … then you’re looking at what’s meant to be a snapshot in time.”

If the new dinosaur hall is filled with “snapshots in time,” then the old one, like those in many current museums, was lined with dinosaur “portraits,” or rows of dinosaur skeletons standing in straight, static and usually scientifically inaccurate poses with no supporting cast of characters to provide visitors with any contextual clues on the lives these giants once led. Talk of renovation began in the 1950s, but serious efforts didn’t begin until 2002, Lamanna says. At that point, museum officials decided if they were going to expand the dinosaur hall — originally built for just one dinosaur — then they would also recreate a host of ecosystems in the dinosaurs’ entire world, something that few museums, if any, have ever done on such a large scale, he says. The result is a chronologically ordered series of exhibits that, upon full completion, will showcase 19 mounted dinosaurs as well as hundreds of other fossilized reptiles, mammals, birds, fish, amphibians, invertebrates and plants.

Carnegie Museum of Natural History |

| The museum now displays their dinosaurs in reconstructed environments, so they can "interact" with other organisms. |

When visitors first enter Dinosaurs in Their Time, they are immediately transported 215 million years back to the Late Triassic. But instead of confronting a dinosaur, visitors are greeted by a skeleton of a phytosaur — a reptile that resembled a modern crocodile — surrounded by strange bamboo-looking vegetation. In fact, the only dinosaur in this exhibit is the small carnivorous Coelophysis depicted in the background mural and as a collection of semiarticulated bones embedded in rock, just the way Carnegie curator David Berman found them. “That’s the gist of this display. When dinosaurs first appeared, it wasn’t like they sprang full-fledged into the 80-foot-long, 30-ton animals that we’re used to seeing,” Lamanna says. “They tended to be small, and they tended to be rare.”

Not only did all the species in the Triassic exhibit coexist in time, but they also coexisted in space, Lamanna says. Rather than gather a generic collection of Triassic-aged species, Lamanna wanted to display together plants and animals from the same rock unit in the American Southwest, the Chinle Group, to add to the exhibit’s authenticity. This theme is carried out through the hall’s other exhibits, including the Jurassic-aged Morrison Formation and Cretaceous-aged Hell Creek Formation exhibits.

After visitors proceed into the Jurassic and weave their way through the gargantuan Apatosaurus-Allosaurus struggle, they’ll find themselves in more familiar surroundings in the hall’s Cretaceous exhibits, where visitors come face-to-face with some of the world’s earliest birds, mammals and flowering plants. For example, visitors can admire the tiny flattened skeleton of Eomaia scansoria, a primitive mouse-sized mammal from the Early Cretaceous of northeastern China, as well as a three-dimensional reconstruction of the same species scurrying along a rock face.

Lamanna hopes visitors notice that a lot of modern organisms got their start in the company of dinosaurs, something most people don’t realize, he says. This fact may well be underscored in the museum’s Hell Creek Formation exhibit, which opens this spring. The centerpiece will be two Tyrannosaurus rex skeletons — one real, one cast — facing off in what Lamanna calls a “grudge match.” An idea currently being tossed around is to place these competitors in a field of bright buttercups, modern flowers for which fossil relatives have been found in the Hell Creek Formation.

Throughout Dinosaurs in Their Time, a variety of interactive touchscreen computers provide visitors with a wealth of information about the biology, geological and ecological context, distribution and evolution of dinosaurs. Although the bulk of the renovation will be finished by this spring, Lamanna sees the entire dinosaur hall as “a work in progress,” something that will be updated continually as scientists learn more and more about life in the Mesozoic.

If you can’t visit the museum in person, be sure to check out its Web site (www.carnegiemnh.org), which offers a cursory look at the exhibit, how it came about and what we know and don’t know about the world of the dinosaurs.

Links:

www.carnegiemnh.org

Book review

|

Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations |

William Ruddiman

In Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations, David Montgomery provides a comprehensive and readable summary of how civilizations have depended on the half-meter of life-generating topsoil that mantles our continents, and why that dependence has failed locally in the past and may do so again across larger scales in the future. The book focuses on agricultural plowing that has, over millennia, stripped away much of Earth’s soil and degraded much of what remains. The primary driver in this enormous transformation of Earth’s surface has been short-term self interest, combined with ignorance of the long-term consequences of our actions.

Most of the book covers case studies of soil use and misuse: in early Mesopotamia and Bronze-Age China, classical Greece and Rome, Central American Maya, pre-Industrial Europe and European pioneers in the United States. Later chapters cover modern issues such as the role of agribusiness and the impact of genetic engineering.

Montgomery notes at least one civilization that kept the land fertile for millennia — the native Amazonian people who composted charcoal, manure, bones and other debris and created rich terra prieta soils. Another example of long-range fertility — the Nile River Valley — owes little to human action and much to the river’s annual gift of both nutrients and freshwater to flush away salts.

Montgomery adds his voice to centuries-old historical debates among historians about why civilizations declined. The list includes: wars, changes in trade patterns, centralization of power and resulting societal rigidity, and environmental factors. In Climate: Past, Present and Future, Hubert Lamb argues that climate played a major role, but historians have largely dismissed his examples of “climatic determinism,” which focused on high latitudes and altitudes of Europe where few people actually lived. More persuasive examples can be found in the arid Eurasian subtropics where intervals of extreme drought brought an end to early empires, such as the Akkadian people of northern Mesopotamia.

Montgomery views resource depletion as more critical than climate, based on examples such as the salt buildup that curtailed agriculture in early Mesopotamia, and the total depletion of trees and soils on Easter Island. He suggests that soil degradation played a strong role in many other societal declines, but he astutely avoids over-exaggeration.

One chapter introduces a philosophical debate that began in pre-Industrial Europe about the interplay among population growth, food production and innovation. In the pessimistic view of Thomas Malthus, Montgomery writes, population growth leads to food shortages and then famine. Over pre-Industrial time, however, famine was not the major cause of human mortality. The European famine of 1313 to 1317 is often cited as the type example of such a catastrophe, but within only a decade, the stricken populations had already rebounded to pre-famine levels. By far the major killers of pre-Industrial humans were the three great pandemics that killed tens of millions of people during the late Roman era, the Medieval Black Death and the European entry into the Americas.

Montgomery contrasts Malthus with William Godwin, who optimistically suggests that food shortages lead to innovations that increase food production. In support of his view, new plows and uses of manure increased food productivity in the Netherlands and England during the Middle Ages despite large population growth.

These two contradictory views are still evident today in many opposing trends. Malnutrition still affects more than a billion people each year, but the percentage of adequately fed humans has been rising for decades. For more than a century, industrial plows have caused unprecedented rates of soil erosion, but “no-till” and other soil-conserving measures are now spreading rapidly. No unexplored virgin lands are left for humans to convert to agriculture, but more than 1.5 million square kilometers of well-watered land at middle and high northern latitudes has reverted to forest in the last few decades and is available for renewed farming. Global population doubled twice in the 1900s, but it will barely double once more before approaching a quasi-stable level soon after 2050 (because wealth allows people to have fewer children). Global warming and the end of cheap oil are new threats, but genetic engineering is a new opportunity.

Montgomery takes note of these opposing factors, and he expresses serious concern about the ongoing loss and degradation of soils and the negative implications for future agriculture. But wisely, he stops short of alarmist projections of outright catastrophe.

Subscribe

Subscribe