|

GEOMEDIA

Check out the latest On the Web links, your connection to earth science friendly Web sites. The popular Geomedia feature is now available by topic.

BOOKS: The Dark — But Fascinating — Side of Science

GAMES: BP Helps the Sims Go Green

BOOKS: Ten Minutes on Supercontinent: Ten Billion Years in the Life of Our Planet

Book review

|

When Science Goes Wrong: Twelve Tales from the Dark Side of Discovery by Simon LeVay. |

A more apt title for author and neuroscientist Simon LeVay’s new book, When Science Goes Wrong: Twelve Tales from the Dark Side of Discovery, might be When Scientists Make Mistakes. The book is a collection of 12 stories united by a common theme that scientists don’t often like to discuss: failure. The examples in When Science Goes Wrong are extreme — the consequences are often fatal. But the book is entertaining, especially because the behavior of many of the scientists seems so incredible, at least in retrospect. More than once readers will find themselves wondering, “What were they thinking?”

LeVay’s book covers a breadth of fields — everything from geology and volcanology to gene therapy and microbiology to nuclear physics and chemistry — over the past 80 years. Despite the magnitude of some of the events, the stories are likely to be new to most readers outside of the given disciplines. Geoscientists, for example, will probably remember the story of Stanley Williams leading a fatal expedition into the crater of Galeras in Colombia in 1993, despite what some say were warning signs that the volcano was due to erupt. But they probably haven’t heard of how questionable statistics and an error in transcribing notes from a lab report to a police report led a forensic analyst in Houston, Texas, to erroneously match a teenager’s DNA to that of a rapist’s in 1999. The mistake cost the teen five years in prison before the error was uncovered.

Each story that LeVay presents could probably anchor its own book, and at times, readers may yearn for more details. But by reading the stories together, several themes about why science goes wrong emerge. Perhaps most obvious — and most unsettling — is the role that human hubris plays. In one chapter, for example, a neurosurgeon goes to great lengths to perform a surgery he’s not qualified to do, with gross consequences.

The pressure to succeed also plays a central role in When Science Goes Wrong. In one example, the principal investigators of a gene therapy trial break rules, cut corners and lie to trial participants, which leads to tragedy. In another chapter, LeVay shows how this drive to succeed can also cause scientists to outright fabricate data.

But human vice isn’t the only culprit behind scientific goof-ups. LeVay also gives examples of how simple human errors — such as failing to convert units of measurements — can bring down multimillion-dollar projects.

Adding to the drama of each story are the scientists’ own interpretations of events. Throughout the book, LeVay has tried, when possible, to interview all major players involved. Reading the characters’ reflections and opinions in their own words and then comparing that to the “facts” as presented by LeVay makes for an absorbing read.

When Science Goes Wrong is not a condemnation of science. LeVay, after all, is a scientist himself. In the epilogue, he assures readers that the preceding chapters are not the norm. “Of course I picked dramatic or memorable examples of scientific failure for this book,” he writes. “They’re not typical of how science can go wrong, because mostly it does so in more mundane ways.” LeVay is right in noting that the results of most scientific errors are pretty harmless (rather than death and destruction), but it seems likely that the types of mistakes and the motivations described in the book are probably pervasive throughout science.

When Science Goes Wrong is written for both the scientist and the layperson to enjoy. But for those who aren’t engrossed in the world of science, the book may offer an eye-opener: Scientists are not infallible. They make mistakes just like everyone else.

BP Helps the Sims Go Green

Electronic Arts |

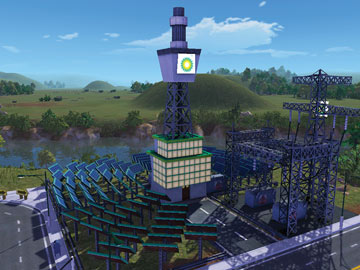

| A branded solar power station in SimCity Societies. |

Like life itself, the video game series SimCity — in which a gamer designs and builds a city according to a variety of scenarios, goals, strategies and philosophies — appears to come in infinite variations. In addition to four SimCity titles, there is a range of Sim-based games that focus on building other kinds of structures, from ant farms to safari parks to meaningful (or meaningless) digital relationships. Last November, the latest version of the SimCity world appeared: SimCity Societies. And this time, there’s smog.

Produced by EA Games in partnership with BP Alternative Energy, SimCity Societies adds a trendy new twist on the series by including such low-carbon, city-powering options as solar panels, wind farms, hydrogen and natural gas plants. You also have the option of using coal-fired power plants, which are cheaper and produce more power — but then you have to deal with the effects of pollution, droughts and heatwaves on your citizens’ health and happiness (along with protesting environmentalists). The choice of power source also affects the Sims’ overall state of mind: They are much happier living next to some types of structures than others. The new game also lets you monitor the power input and output of your buildings and even set up a Carbon Exchange, modeled after the Chicago Climate Exchange, a voluntary greenhouse gas emissions trading system that aims to limit pollution. Through the Carbon Exchange, your city can generate additional revenue if its carbon dioxide emissions are lower than average. As a result, not only do you control the day-to-day lives of hundreds or thousands of simulated people, but also their air quality.

“With SimCity Societies, we have the opportunity not only to demonstrate some of the causes and effects of global warming, but also to educate players [about] how seemingly small choices can have a big global impact,” said Steve Seabolt, EA’s vice president of Global Brand Development for The Sims, at a press rollout announcing the new game last October.

The timing of the partnership was right for BP, said Carol Battershell, vice president of BP Alternative Energy, at the rollout. Set up in 2005, BP Alternative Energy plans to invest $8 billion in solar, wind, hydrogen and natural gas power projects over 10 years. So BP approached EA, looking for a way to showcase its alternative energy programs and to reach a younger generation by mixing a little education with a lot of entertainment.

“EA was developing the next iteration of the SimCity series at the same time that we were looking for opportunities to raise awareness about low-carbon power choices,” Battershell said. BP saw the partnership as an opportunity: “In our collaboration … we can provide education on the issues surrounding climate change, its association with carbon emissions and the ability to take early positive action through low-carbon power choices,” she said. And in an ingenious bit of marketing, the various alternative energy sources in the game — wind, solar, natural gas and hydrogen power — bear the BP logo (the heavy carbon polluters like coal and oil do not, but a few 1950s-style gas stations do).

For all its informational tips, its creators are quick to note that SimCity Societies is still a game, not an educational tool. But as a video game with an alternative energy angle, it has had some trouble finding its niche, says Daniel Alioto, assistant producer of The Sims Division at EA Games. As the game focuses as much on the Sims’ culture as on their architecture, one potential target is women, who are a growing, but still minority population of video game buyers. But so far, the game hasn’t sold as well as some of the other SimCity titles, Alito says.

EA Games is not entirely surprised by that, he says, because in this game, “we took a different route.” Given that its focus is slightly different, SimCity Societies does not actually fall within the hierarchy of the four previous SimCity games — “it’s not SimCity 5,” he says. “It’s a different game than it used to be.”

As with all SimCity games, SimCity Societies is a game of choices — you choose what types of buildings (homes, businesses, gardens, factories) to build where. The new game, however, also lets you decide on your society’s “values” — for example, whether your Sims prefer to be creative, spiritual, knowledgeable and/or productive.

When I tried the game, I decided that my Sims — the residents of Fun City — were a creative lot. Thus, they became happier and more satisfied with life whenever I dropped a new mural, community garden or ice cream shop into their world. To keep them content in the long term, the game informed me, Fun City would need a critical mass of distractions as well as jobs. To pay for my businesses, schools and entertainment venues (such as a movie theater, a Willy Wonka-ish chocolate factory and a scattering of haunted houses), my city needed revenue.

It also needed power. To try being fully green, I began by powering my city with only a smattering of major wind farms, but as my city grew, its power needs mounted and the wind farms weren’t quite keeping up. So, I gave in to the pressure and added a natural gas power plant nearby, and watched as the pollution from my city began to rise (not much, but still). It was a lesson in decision-making and patience.

One glaring omission in a game with a climate education angle was a similar emphasis on information about vehicle pollution. Power plants account for about 40 percent of U.S. carbon dioxide emissions, according to a November 2007 report by the Center for Global Development, an independent policy think tank. But motor vehicles have a big impact, too — for example, congestion in Los Angeles has placed the city squarely among the top most polluted U.S. cities, according to the American Lung Association. Cars do affect pollution levels in the game, and SimCity Societies also offers options such as subways and buses. Still, the game’s educational thrust really focuses on power plants.

Like the other games in its genre, the endless possibilities in SimCity Societies make for absorbing entertainment. And the fact that the power solutions weren’t easy and included some realistic tough choices between power supply, costs, health and happiness added to the newest Sim game’s depth.

Book review

|

Supercontinent by Ted Nield. |

Thomas Wagner

In his book Supercontinent: Ten Billion Years in the Life of Our Planet, author Ted Nield doesn’t waste any time. He dives right into his picks for earth science’s greatest hits with rapid-fire delivery on the evidence and controversy surrounding each. Loosely centered on supercontinents — the giant landmasses that can form as Earth’s continents continue their perpetual dance of collision, merging and breakup — Nield also covers the origin of life, deep-time climate change, mythical lost continents and the character of the scientists who study it all.

Overall, the book is a triumph, connecting a diverse range of subjects in an insightful manner. Nield begins the book 250 million years into the future, with the formation of the next supercontinent — Novopangea or Pangea Ultima, depending on whether the Atlantic or Pacific ocean basin closes first. He then turns to the past, highlighting great and sometimes unsung geologists, as well as the lengthy string of evidence that proves that Earth’s surface is in motion. The book’s forays include descriptions of the events and debates surrounding the identification of ancient glacial deposits in the tropics, the development of paleomagnetic and gravity measurements, and the curious distributions and relationships among animals identified during the great zoologic expeditions of the 1800s.

Much of this has been written about before, but Supercontinent also frames the timeline of discoveries with the development of mythologies of lost continents such as Lemuria or Kumarikkantam (fictional locations). Although some reviewers have called Nield’s forays into mythology dead ends, they do add some intrigue, especially considering that these myths continue to be mainstays of some New Age religions.

Mythology aside, the science is sound. Nield grounds the work by discussing how plate tectonics accounts for everyday things, from the geologic forces that cause sinkholes in England — which inspired Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland — to the worldwide distribution of petroleum and coal. His breadth of knowledge makes these sections a pleasure to read. Descriptions of ancient continental connections and the closings and openings of ocean basins are particularly engaging and reminiscent of Simon Winchester’s books. They are, however, often difficult to follow without maps. (A quick consult of a plate tectonics Web site or other works on plate tectonics helps.)

Nield makes no claims of comprehensiveness, but the book’s historical focus misses an important theme: why we continue to study supercontinents and plate tectonics. Relevant current research, such as studies on how plates tear themselves apart and how erosion paradoxically causes mountains to rise, is left out. The book also neglects mantle convection, the driving force behind plate motion. Seismic tomography now offers CAT scan-like views of deep Earth, complete with sinking cold zones and rising hot ones, and shows deep keels beneath continents. Geochemistry also shows that some components of subducted plates return to Earth’s surface at hotspots such as Hawaii. And while Nield briefly addresses historical biogeography, he ignores contemporary questions such as how mammals made it to Australia and why similar dinosaur fossils are found in such disparate locations as China and Antarctica. The book also fails to reference Naomi Oreske’s The Rejection of Continental Drift: Theory and Method in American Earth Science. Published in 1999, it is the reference work on the clash of American and European science described throughout the book, though Nield certainly adds a unique perspective.

Criticisms notwithstanding, Nield’s writing shines in Supercontinent’s brief, lucid descriptions of the major controls on the Earth’s climate. In just a few pages, he succinctly describes orbital, atmospheric and oceanic connections, and shows how variations in continental position affect global weather. Along the way, he tackles one of the more complex but important aspects of climate science: interpreting the tremendous rise and fall of atmospheric carbon dioxide found in the geologic record. The global carbon cycle is perhaps the most misunderstood aspect of climate change, and Supercontinent does as admirable job of explaining how carbon dioxide is drawn down by weathering. This is a critical discussion for the current climate change debate, in which some have used these deep-time variations to erroneously claim that the current trend is not anthropogenic. This section would make for a nice standalone publication.

So who should read Supercontinent? Anyone. For the lay reader, it is an enjoyable account of the major events in the life of Earth, while for the geologist there is a unique coupling of cutting-edge science with the history of geology. But I imagine the book will be most useful to teachers. It is a treasure trove of interesting anecdotes with which to spice up lectures, such as Robert F. Scott carrying 35 pounds of important rock samples to his cold end, though most speculate that he picked them up on the return trip from the South Pole. And if you find any sections dragging, which you probably will, skip them and go on to the next part that intrigues you. Most of the book is written in standalone chunks, and it would be shame to miss the gems.

Subscribe

Subscribe