Geotimes

Untitled Document

Geomedia

Geotimes.org offers

each month's book reviews, list of new books, book ordering information and new

maps.

Check out this month's On

the Web links, your connection to earth science friendly Web sites. The

popular Geomedia feature is now available by

topic.

Selling extreme life on the extreme

screen

Books:

Touring the planet: Earth: An Intimate History

On the Shelf:

Climate Change Picks from Kim Stanley Robinson

Maps:

New View of North America

Selling

extreme life on the extreme screen

At

one point in the movie Aliens of the Deep, shown in 3-D, the bell of

a translucent jellyfish undulates out of the screen toward the viewers in the

IMAX theater. A sheet of gelatinous, translucent ghostly white skin ripples

in waves, hovering before the audience, and the image is so detailed that the

surface crenulations are clearly delineated, looking a little like crinkles

on the surface of a cantaloupe. The unknown species’ organs appear and

disappear behind its waving bell, and wispy tentacles are barely visible.

At

one point in the movie Aliens of the Deep, shown in 3-D, the bell of

a translucent jellyfish undulates out of the screen toward the viewers in the

IMAX theater. A sheet of gelatinous, translucent ghostly white skin ripples

in waves, hovering before the audience, and the image is so detailed that the

surface crenulations are clearly delineated, looking a little like crinkles

on the surface of a cantaloupe. The unknown species’ organs appear and

disappear behind its waving bell, and wispy tentacles are barely visible.

The clarity and closeness of the deep sea creatures in Aliens of the Deep

is one of the main reasons to see what is, in the end, a beautiful film, half

documentary-style and half fantasy. Viewing the movie feels like taking a major

trek to the bottom of the sea — a trek I took in April, while viewing the

movie with several scientists in New York City.

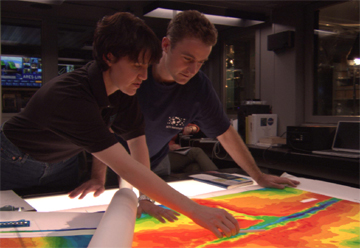

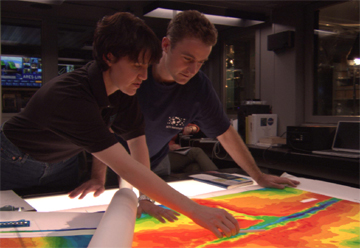

As part of a team of scientists taking part

in Aliens of the Deep, Maya Tolstoy and Kevin Hand had their first opportunities

to dive in submersibles, to visit deep sea hydrothermal vents. Photo copyright of Buena Vista Pictures and Walden Media, LLC.

Produced and directed by James Cameron (of Titanic fame, among other

big-budget blockbusters), this IMAX adventure follows Cameron and a team of

young scientists, from biologists to oceanographers, who travel in submersibles

to explore deep sea vents and the creatures that live at such extremes. Using

four submersibles — which is often more than most scientists get access

to — the team visited several vent sites with names like Snake Pit and

the Lost City, during two ocean-going voyages in 2003 (see Geotimes

Web Extra, March 10, 2005).

At one point, an animated sequence shows the exact scale at which these intrepid

explorer-scientists are diving to get to their targets: From a long shot of

Earth, the eye of the camera plummets down through the atmosphere, plunges past

the ocean’s surface and speeds down to the kilometers-deep trenches “that

ring the planet like seams on a baseball.” The sea chimneys tower like

immense stalactites, with the tiny animated submersibles flitting about them.

The film’s narrative follows the scientists at work, including biologist

Dijanna Figueroa, a graduate student at the University of California, Santa

Barbara, who starts off the journey by describing the premise of the sun’s

life-sustaining energy. Only in the 1970s, after the first discoveries of deep

ocean vents and the chemotrophic — or chemical-eating — communities

that live there, did scientists suspect that life could exist without photosynthesis.

Cameron uses this point to establish a potential model not only for how life

started on this planet, but also how it may have begun elsewhere.

For Maya Tolstoy, an oceanographer and geophysicist at Columbia University’s

Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, the trip with Cameron was a “ship of

opportunity,” allowing her to deposit her seismometers on the ocean floor

within three months of getting funding — more quickly than had she followed

the calendar for a normally scheduled cruise. She says that going down in a

submersible for the first time also gave her the chance to see where she was

sending her instruments, something she had never done before. “It’s

a privilege to do this kind of work,” Tolstoy says.

Kevin Hand, a theoretical astrobiologist and post-doc at Stanford University

and the SETI Institute, had never gone to sea before, and his first experience

gave him the chance to explain to the audience and his biologist shipmate how

a system like the hydrothermal vents does not necessarily need Earth-like plate

tectonics — if only in a brief reference. “All you need is seawater

interacting with hot rocks,” he said about halfway through the movie, in

the first blatant reference to geology.

Tolstoy later clarified what Hand meant after we watched the movie: “On

Earth, much of our faulting is due to plate tectonics,” she says, so the

water can circulate in deep rocks that are still warm. But faulting “can

be caused by other stress changes, such as ice loading or volcanism,” she

says. “You just need an active system,” such as the one described

in the film’s excellent animated sequence on the Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter

(JIMO) project.

Jupiter has an immense gravitational effect on its moons, causing them to pulsate

as they orbit the huge planet. That tidal pull causes crustal cracking and creates

frictional heat, giving rise, for example, to Io’s monstrous volcanoes.

JIMO has the potential to explore Jupiter’s satellites Ganymede, Callisto,

Io and — the most alluring — Europa. That moon has a skin of ice that

may harbor an ocean beneath and is the most likely of all the candidates in

the solar system to harbor life, even if it will probably be only microbial.

“If you find microbes,” says Michael Rampino of New York University,

who watched the film with me, “that would be fantastic enough.”

Cameron’s excitement at the prospect of meeting new life on Earth and elsewhere

is palpable throughout his film, perhaps most embodied by some flights of fancy

toward the end, which depict digitally created octopus-like extraterrestrials

in a glowing underwater city (and which irked some reviewers and scientists).

“We have to go there” is the cry, both to the bottom of the ocean

and to space to see what can be found, a sentiment voiced by scientists and

Cameron alike. Overall, I walked out feeling not only exhilarated and exhausted

by my virtual journey, but also feeling that Cameron is a good salesman of ocean

and space exploration.

But some people aren’t buying into it. Because of its references to the

origins of life and evolution, several IMAX theaters have passed on Aliens

of the Deep and what could be considered a companion to this film, Volcanoes

of the Deep Sea. A block of theaters in the South, many of which are associated

with science centers and museums, were “reticent to take the films,”

says Rich Lutz of Rutgers University in New Jersey, the science director for

Volcanoes of the Deep Sea. The theaters claimed that the two movies “wouldn’t

sit well with an audience that was creationist,” he says.

The most vocal in its rejection of the films was the Fort Worth Museum of Science

and History in Texas, Lutz says. After a New York Times article “spurred

a lot of attention [regarding] how important it was to have films like that,

referring to evolution,” Lutz says that “they got a lot of phone calls.”

The center’s new director and board reversed the decision, as did the Discovery

Place in Charlotte, N.C. Volcanoes’ director Stephen Low introduced the

film at its first showing there in April. The controversy may prompt other IMAX

theaters to show the films or bring them back into rotation, Lutz says; Aliens

has been shown at 24 IMAX theaters around the United States, and Volcanoes

at eight, plus one in Taiwan.

Cameron gave some funding to Volcanoes of the Deep Sea, but Aliens of the

Deep visits many of the same places, and the overlap in subject matter and

release dates has created some awkwardness in the production and scientific

communities. Still, the two are “a nice one-two punch in terms of oceanographic

research … and the wonders of science,” Lutz says. “[Cameron’s]

film certainly can excite the younger members of the audience about science,”

while serving as a precursor to Volcanoes of the Deep Sea, for those

who are interested in finding out more.

Perhaps best of all of Cameron’s pitches is that he shows what scientists

do, Rampino says. “My students would think it was cool,” he says.

Cameron conveys a “sense of exploration” and excitement by showing

scientists in action, using robots and other tools available. “I’d

be excited, too,” Rampino says.

The high school students in the audience the day we saw the movie in New York

City were all enthusiastic, if a bit turned off by the fantasy ending. Of the

half dozen I spoke to, the boys were very pro-science and exploration. The girls,

however, were less so, despite all the female scientists shown larger than life:

The girls wanted more scares and 3-D tentacles reaching out to them from the

bottom of the sea.

Naomi Lubick

Link:

"Revisiting the

Lost City," Geotimes Web Extra, March 10, 2005

Back to top

Book review

Earth:

An Intimate History Earth:

An Intimate History

by Richard Fortey,

Knopf, 2004.

ISBN 0 3754 0626 3.

Hardcover, $30.00.

|

Touring the planet

Callan Bentley

In Earth: An Intimate History, paleontologist Richard Fortey of the

Natural History Museum in London takes readers on a tour of his favorite planet.

Don’t let its 400-plus pages scare you off — this beautiful book is

a compelling overview of the wonders of geology around the world, melded with

a memoir of the author’s own experiences.

Reading Earth brings two great joys. The first is that Fortey makes some great

connections between geology and day-to-day human life. Take for example, the

origin of the “dollar” in a silver mine in what is now the Czech Republic.

The village is Joachimsthal, and its mine was known as Joachimsthaler. This

moniker was shortened to “thaler” to describe the coins minted from

Joachimsthaler silver. “Thaler” became “daler” in Dutch,

and eventually the word was handed down to us as “dollar.” This etymological

investigation provokes Fortey to muse upon the nature of metals, minerals, economic

geology and world trade.

Many of the connections he draws are ruminations on how geology controlled human

history, and he weaves in quotes from many literary sources as he lets the planet

tell its tale. In Italy, for example, the mythology of doom that surrounds Vesuvius

and its volcanic brethren ultimately informed geologic studies there. Throughout

the book, gorgeous color plates illustrate some classic localities from the

rock record, as well as bizarre images from hotel labels, coins, billboards,

vases, temples, lava lamps and the like — all of which are somehow tied

to the history of the planet. Fortey’s greatest strength as an author is

his delight in sharing these connections. All of his readers will revel in the

myriad ways our civilization has been shaped by geological nuance.

The second great treat is that this “intimate history” will be accessible

particularly to earth scientists. So much of a scientist’s reading consists

of dry technical writing. In comparison, it is an unmitigated delight to read

a broad view of the planet’s tectonic development written in a fluid and

uncramped style. (Fortey is a trilobite specialist, but most of this book focuses

on tectonics.)

Fortey waxes philosophical at almost every turn, but his musings never take

priority over the science. In Hawaii, for example, the touristy towns force

him to ponder the word “Eden,” while the multicolored beaches provoke

a contemplation of the deeper meaning of sand. Later, in a chapter on the Alps,

he practically squeals with delight over his visit to the Glarus nappe, a classic

locality showing ancient rocks thrust over the top of much younger strata.

Earth is not just the story of the planet, however; it is also the story of

geologists. Fortey enthusiastically recounts his scientific predecessors’

brilliant fieldwork and clever deductions on the movements of rocks. By considering

each aspect of the process — observation, deduction and appreciation —

he makes geology an insightful meditation on the lessons of our planet.

Fortey’s U.K. pedigree shows through in his writing. Quaint British expressions

like “pick a back” and “jiggery pokery” grant a quirky,

archaic flavor to his prose (especially to American ears). Add to this his reminiscences

about his quintessential undergraduate textbook (by Arthur Holmes), which pop

up again and again, and you never lose sight of the fact that this book was

written by a Briton.

Fortey is at the top of his game with this book. His intimacy with the planet’s

history is a treat to witness. Earth is for anyone who has ever paused on a

walk outside, taken a breath of fresh air and reflected with immense satisfaction

on how much fun geology is.

Bentley is a Geotimes

contributing writer and a visiting geology professor at George Mason University.

Back to top

On the Shelf

Climate

Change Picks from Kim Stanley Robinson

In an interview with Geotimes, sci-fi author Kim Stanley Robinson mentioned

the following publications as key background reading for his research for Forty

Signs of Rain, his recent fiction book that includes a future climate vastly

different from today’s.

The Two-Mile Time Machine: Ice Cores, Abrupt

Climate Change and Our Future

by Richard B. Alley, Princeton University Press, 2002. ISBN 0 6911 0296 1. Paperback,

$18.95.

Alley gives an account of fluctuating climate throughout geologic

history, which he and others have determined using annual layers from ice cores.

Suggesting that our temperate climate may be coming to an end, he explains what

we need to know to understand climate change.

The Long Summer: How Climate Changed Civilization

by Brian Fagan, Basic Books, 2004. ISBN 0 4650 2281 2. Hardcover, $26.00.

Climate change is not a new phenomenon; humans have adapted to change

throughout history. (See Geotimes,

June 2004, for a complete review of The Long Summer.)

A Brain For All Seasons: Human Evolution and

Abrupt Climate Change

by William H. Calvin, University of Chicago Press, 2003. ISBN 0 2260 9203 8.

Paperback, $15.00.

Calvin takes us around the world and back in time to discover how

our ancient ancestors survived climatic changes evolutionarily, by increasing

their intelligence and complexity.

Abrupt Climate Change: Inevitable Surprises

by the Ocean Studies Board, National Research Council, 2002. ISBN 0 3090 7434

7. Hardcover, $49.95.

This comprehensive report addresses climate change and its impacts,

as well as possible implications for the future. To read more about the report,

see the article “Cracking

Abrupt Climate Change,” which appeared in the February 2002 Geotimes.

Back to top

New View

of North America

For the

first time, a geologic map of North America portrays the relationship between

the geology of the continent and the geology of ocean basins. The previous geologic

map of North America, printed in 1965, was published before the general acceptance

of plate tectonics and when the geology of seafloors was largely unknown. The

new map provides a comprehensive perspective of the geology of the region at

the conclusion of the 20th century.

For the

first time, a geologic map of North America portrays the relationship between

the geology of the continent and the geology of ocean basins. The previous geologic

map of North America, printed in 1965, was published before the general acceptance

of plate tectonics and when the geology of seafloors was largely unknown. The

new map provides a comprehensive perspective of the geology of the region at

the conclusion of the 20th century.

The new 1:5,000,000-scale geologic map, The Geologic Map of North America,

covers about 15 percent of Earth’s surface. It distinguishes 939 geologic

units, of which 142 are offshore, and includes locations of volcanoes, calderas,

impact structures, axes of submarine canyons, spreading centers, transform faults,

magnetic isochrones and subduction zones. The compilation of a geologic map

of such a large area and detail was complex and took almost 25 years to complete

— spanning a time when cartography changed from traditional methods to

digital techniques.

A 28-page text accompanies the map that discusses the history of small-scale

geologic maps of North America dating back to the 18th century, how the current

map was made and the sources of information. This text also explains how to

use the map with its wealth of information in geologic map units and map symbols.

A map of this scale and detail with a continuation of geology from onshore to

offshore should provoke new ideas on geologic processes through interpretation

of geological patterns. Also, the map will play a role in training earth scientists

and aid in planning new research.

The map was a joint effort of the Geological Society of America, U.S. Geological

Survey, Geological Survey of Canada and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution,

as part of the Decade of North American Geology project.

Randall Orndorff of the U.S. Geological Survey compiled

the Maps column this month, with contributions from John C. Reed Jr., co-author

of the new North American map.

The Geologic Map of North America, Continental Scale Map 001, comes as 3 color

sheets (northern, southern, and legend), 74 X 40 inches, and can be obtained folded

for $150 (GSA member price $120) or rolled for $155 (GSA member price $125) and

includes a 28-page text from GSA Sales and Service, P.O. Box 9140, Boulder, Colorado

80301-9140, or from www.geosociety.org/bookstore/.

Back to top

Untitled Document

At

one point in the movie Aliens of the Deep, shown in 3-D, the bell of

a translucent jellyfish undulates out of the screen toward the viewers in the

IMAX theater. A sheet of gelatinous, translucent ghostly white skin ripples

in waves, hovering before the audience, and the image is so detailed that the

surface crenulations are clearly delineated, looking a little like crinkles

on the surface of a cantaloupe. The unknown species’ organs appear and

disappear behind its waving bell, and wispy tentacles are barely visible.

At

one point in the movie Aliens of the Deep, shown in 3-D, the bell of

a translucent jellyfish undulates out of the screen toward the viewers in the

IMAX theater. A sheet of gelatinous, translucent ghostly white skin ripples

in waves, hovering before the audience, and the image is so detailed that the

surface crenulations are clearly delineated, looking a little like crinkles

on the surface of a cantaloupe. The unknown species’ organs appear and

disappear behind its waving bell, and wispy tentacles are barely visible.

Earth:

An Intimate History

Earth:

An Intimate History

For the

first time, a geologic map of North America portrays the relationship between

the geology of the continent and the geology of ocean basins. The previous geologic

map of North America, printed in 1965, was published before the general acceptance

of plate tectonics and when the geology of seafloors was largely unknown. The

new map provides a comprehensive perspective of the geology of the region at

the conclusion of the 20th century.

For the

first time, a geologic map of North America portrays the relationship between

the geology of the continent and the geology of ocean basins. The previous geologic

map of North America, printed in 1965, was published before the general acceptance

of plate tectonics and when the geology of seafloors was largely unknown. The

new map provides a comprehensive perspective of the geology of the region at

the conclusion of the 20th century.