|

GEOMEDIA

Check out the latest On the Web links, your connection to earth science friendly Web sites. The popular Geomedia feature is now available by topic.

EXPLORATION: A Longer Walk in the Woods

BOOKS: Q&A with Sidney Perkowitz, author of Hollywood Science: Movies, Science, and the End of the World

B00KS: The Evolving Presentation of Evolution: Science, Evolution and Creationism

A Longer Walk in the Woods

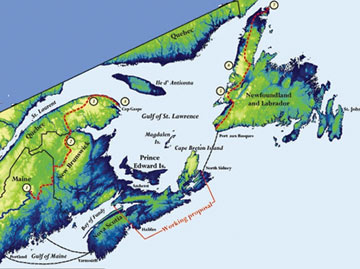

| Currently, the International Appalachian Trail/Sentier International des Appalaches (IAT) passes through Maine, New Brunswick, Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador and, most recently, Nova Scotia. |

In 2005, Joe “Cotton Joe” Norman set out from Springer Mountain, Ga., to hike the Appalachian Trail (AT), which runs from Georgia to Maine. Thousands of hikers have walked all or parts of the historic trail — one such trip was memorialized by Bill Bryson in A Walk in the Woods — and Norman had every intention of following in their footsteps, ending his hike at Maine’s Mount Katahdin, the AT’s northern finish line.

But along the way, Norman met another hiker who gave him some interesting news: Norman’s hike didn’t have to end in Maine. Instead, if he had the time, the money and the stamina, he could keep heading north, following a newer trail that starts near Mount Katahdin and winds into the Canadian Maritime Provinces, ultimately ending at the sea.

Norman — who earned his trail name “Cotton Joe” for wearing cotton T-shirts, not the best idea for backpacking — decided to go for it. After finishing the full 3,200 kilometers of the AT, he descended once again from Mount Katahdin and went looking for the nearby head of the younger trail, called the International Appalachian Trail/Sentier International des Appalaches (IAT/SIA). Seven months after starting out from Georgia, he finally ended his hike at Cape Gaspé, Quebec.

The IAT is the brainchild of Dick Anderson, a fisheries biologist and former commissioner of Maine’s Department of Conservation, who dreamed it up as he was driving along a Maine interstate in 1994. “It just came to me,” Anderson says. It was, in its way, a philosophical idea, he says: The Appalachian Mountains don’t end abruptly in Maine — they go on into Canada. Shouldn’t there be a trail that does the same?

Geologically speaking, it makes sense to continue a trail along the Appalachians, says Sandra Barr, a geologist at Acadia University in Nova Scotia, Canada. “I think the wide diversity of the geology here is unsurpassed. You would never have time to get bored, because it changes very rapidly.”

Stretching from Alabama to Newfoundland, the Appalachians have a long and complex history. Several phases of tectonic collisions formed first the northern part of the Appalachians, beginning about 450 million years ago, and later the southern part, beginning about 350 million years ago. The region also includes many exotic terranes, remnants of crust from other landmasses farther south that moved northward and became tacked back onto the North American continent during this busy period. Eventually, 180 million years ago, the northern Atlantic began to split apart, separating Africa from North America and scattering parts of the mountain chain across the Maritime Provinces.

Because of this complicated history, the geology along the route that hikers traverse changes rapidly. For example, all of New Brunswick, the eastern parts of Quebec and most of Nova Scotia are “exotic,” offering a diverse array of geology, Barr says. In Newfoundland, the IAT crosses a famous area where pieces of mantle rock called ophiolites are exposed at the surface.

Joe Norman |

| A hiker along the IAT in Newfoundland treks by dramatic views, such as Partridge Pond Falls in the province’s northern peninsula. |

With support from Maine’s incumbent candidate for governor at the time, Joe Brennan, the proposal to form the IAT quickly made the news across Canada, Anderson says. Throughout the 1990s, trails were cut through the Appalachian Mountains in Maine, New Brunswick and Quebec. In 2003, Newfoundland joined the IAT, opening its first section of trail in 2006 (although thru-hiker Norman wasn’t yet aware of that). From Katahdin, Maine, the trail heads north to eventually follow the U.S.-Canadian border until it heads across into New Brunswick. From there, it goes to Mount Carleton, the highest point in New Brunswick, and then into the Chic-Choc Mountains of Quebec’s Gaspé Peninsula. To get to the Newfoundland section, hikers must take a ferry across the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Many seasoned thru-hikers, including Norman, see the IAT as another chance to hike through beautiful backcountry. “I count them as one single trail,” Norman says. “It’s one mountain chain.”

That view is only partly shared by the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC), which has been responsible for protecting the AT from development for the last 80 years. The ATC is supportive of the younger trail, but stresses that the two trails are distinct. “When they first got started, there was some concern over the name, and where things would connect,” says Brian King, a spokesman for the ATC. Rather than linking up at Mount Katahdin, for example, hikers who want to find the head of the IAT must go east around Katahdin’s location in Baxter State Park. “But the board talked about it and decided, well, it’s more hiking opportunities. That’s a good thing," he says.

Much of the IAT connects pre-existing trails and old logging roads, meaning that parts of the IAT are less remote and open to bikers and people traveling between towns, Norman says. As the trail progresses, however, new sections are continuously being cut into more remote areas. The IAT also doesn’t yet have some of the conveniences of the more established trail, with fewer lean-tos to shelter from the rain, although cabins are being built.

Joe Norman |

| Looking west from the IAT in Newfoundland, toward the Gulf of St. Lawrence. |

Still, hikers appear interested. “We’ve had 96 people who have hiked from Katahdin to Cape Gaspé,” while 13 more continued on to the trail’s current terminus at the historic Viking settlement L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, Anderson says. In 2007, a Nova Scotia chapter joined the IAT, completing a section of trail in October that connects to the Newfoundland trail.

In 2006, Norman returned to the IAT to hike the Newfoundland portion he hadn’t known about the year before. He took three weeks off to help cut new sections of trail, and returned to help cut more trail in the summer of 2007.

With chapters in Maine, New Brunswick, Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Nova Scotia, the IAT has had a connecting effect, Anderson says. Interest in extending the trail has even come from overseas, where the opening of the Atlantic Ocean carried remnants of the Appalachians to Spain, Portugal and northwestern Africa, and also to eastern Greenland, western Norway, and Scotland and Ireland — lands that, IAT planners note, further both Newfoundland's geological and cultural connections to Viking lands.

“Thinking beyond borders was our theme,” Anderson says. “Maine is the only state bordered by only one other state; the rest of our boundary, on three sides, is Canada. People in Newfoundland share the same mountains with people in Alabama, so we’re using the mountains as a way to connect people together.”

Links:

www.internationalat.org

Q and A with Sidney Perkowitz, author of Hollywood Science: Movies, Science, and the End of the World

|

Hollywood Science: Movies, Science, and the End of the World |

Research physicist Sidney Perkowitz of Emory University in Atlanta, Ga., has been seeking artistic ways to convey the wonders of science to non-scientists for nearly two decades. Author of four popular science books, two plays, a performance-dance piece and a new screenplay (about cloning), Perkowitz’s latest book, Hollywood Science: Movies, Science, and the End of the World, is an affectionate survey of more than 100 science/science fiction films that considers what they did right, what they did wrong and what they did really wrong.

Perkowitz says he has had a lifelong appreciation of science fiction, and his interest in ultimately becoming a scientist was at least partly due to the influence of movies such as The Day the Earth Stood Still and Destination Moon. In the first half of the book, organized into sections on alien invaders, planetary forces and classic scientific hubris gone wrong, Hollywood Science summarizes the movies’ plots and then analyzes them for scientific inaccuracies. The book’s third, and most compelling, section deals with the impact of these movies on society, such as how Hollywood portrays scientists. Perkowitz also discusses which movies manage to tell a rollicking good story while still accurately conveying the spirit of scientific discovery and research (if not necessarily every detail), as well as which utterly fail.

Perkowitz spoke with Geotimes reporter Carolyn Gramling about how Hollywood continues to have a significant impact on the sometimes rocky, sometimes reverent relationship between science and society.

CG: Why did you decide to write this book now?

SP: My last book was about robots and androids and how they appear in science fiction films, so part of it was personal timing. And I think it’s an important time to worry about how the public perceives science, and how it’s portrayed on screen. Science seems under assault these days, so I wanted to get the facts out about it.

CG: You start by talking about science fiction, which offers a more “extreme” picture of science but also brings back a sense of marvel about it. Has interest in science fiction changed?

SP: I think more people are interested in science fiction than in the past. Science fiction films reach some of the biggest audiences in the world. They’re great works of imagination, and make you think about alternate possibilities, not just technologies but also projections about where society will go. I only have anecdotal evidence for this, but I also think [science fiction] inspires a lot of kids to become scientists. It’s a hidden benefit that hasn’t been explored enough, but I think it’s real.

CG: One of the issues you examined was how scientists are actually portrayed in these movies.

SP: Yes. There are two extreme levels: you have Pierce Brosnan, [a geologist in the volcano movie Dante’s Peak]. That’s one extreme. At the other are the white lab coats, beards and eyeglasses. I don’t think the average American has met many real scientists — unless you hang out at a university — and I think people do form their opinions through these films.

CG: If there were an Academy Award for “Best Portrayal of a Scientist,” whom would you give it to?

SP: Jodie Foster in Contact is one. She’s a pretty good representation of an intense, driven kind of scientist, without caricature — they don’t dress strangely but are very dedicated. There’s another one, a character in the movie Good Will Hunting. The mentor in the movie is an MIT math professor who has won the Fields medal, the Nobel Prize of mathematics. He’s at the pinnacle of his profession, but it doesn’t make him a fulfilled human being, and if he can’t do it, then his mentee will. It’s a very good portrait of an extremely driven scientist who’s wholly devoted to his science; it’s a real image, and the portrayal [by Stellan Skarsgård] was quite good.

CG: You talk about the balance that some movies try to strike between scientific accuracy and telling a good story. How can a movie do that successfully?

SP: One way to do it is to allow one willing suspension of disbelief in the plot. For example, there’s a whole class of movies with faster-than-light travel. So you allow that. But then after that, you try to put things in a coherent and logical way. For example, the movie Dante’s Peak, with an “extinct” volcano [returning to life and] erupting in the Cascades — that’s pretty unlikely, but given that that central event happens, a group of geologists also looked at the film and the ensuing science gets a rating between B-plus and A-minus. On the other hand, there’s the movie Volcano, which has multiple suspensions of disbelief — you have to suspend disbelief that the San Andreas Fault could cause a volcano, but even after that, the rest of the science still isn’t very accurate.

CG: In fact, you gave The Day After Tomorrow a “Special Award” for highlighting important issues even at the expense of strict accuracy.

SP: Yes, because it does have some value for science and society, even though the science was hyped — and there are scientists who might go for my throat for that. [Laughs.] People who are true climatologists can say with complete justice that the movie exaggerates, but sociological studies suggest that the movie did make people more aware of global warming as a problem. Going back to the ’60s, you could make the same argument about nuclear war — it may be a little exaggerated, but one science fiction author [David Brin] has suggested that films like Dr. Strangelove may actually help push us back from the brink of destruction.

CG: And you save some special contempt for The Core.

SP: Even once you get past the premise that Earth’s core stops spinning, everything is wrong. They talk about Earth’s “electromagnetic field,” rather than its magnetic field. And there’s a person surviving temperatures in Earth’s core as hot as those on the sun’s surface, and all he does is pant a little bit before he dies. In reality he’d vaporize. It’s just contemptuous of the audience.

CG: You’re a film enthusiast as well as a physicist, and your love for these movies, even the cheesy ones, comes through clearly. What lessons can Hollywood take from your book? Or scientists?

SP: One step would be to listen to whatever science advisors they take on board, and get them in early in the production process. Once you’ve shot film it’s not going to change. The National Science Foundation has gotten interested in this, and is thinking about creating a roster of scientists who would be willing to advise and can understand the difference between a story and a scientific lecture. A lot depends on the scientific community: They need to accept that movies won’t change in a radical way, the science will be screwed up — but let’s use it to teach real science. I think our attitude has to merge with the film studios’ attitudes.

The Evolving Presentation of Evolution

|

Science, Evolution, and Creationism is available to download for free on the National Academy of Sciences’ Web site (nationalacademies.org/evolution).

National Academy of Sciences |

In January, the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) and the Institute of Medicine released Science, Evolution, and Creationism, the third edition of a booklet designed to help the public better understand evolution. The new edition clarifies the differences between science and creationism, while simultaneously emphasizing that evolution and religion are not incompatible.

Science, Evolution, and Creationism is a readable primer on the subject of evolution. Written by a panel of 13 scientists and two high school science teachers, the 88-page booklet is divided into three main sections: a chapter that explains what evolution is and defines science; a chapter that provides concrete evidence in support of evolution; and a chapter that outlines why creationism is not science and, therefore, does not belong in the science classroom. The booklet also makes the argument that understanding evolution is vital to the future of the United States. Using examples of how evolution plays a role in understanding health and treating disease and how it improves agriculture and industry, the booklet highlights evolution’s practical importance to society.

Despite overwhelming scientific evidence, religion is often — unnecessarily — a barrier to people accepting evolution, says Glenn Branch, deputy director of the National Center for Science Education (NCSE) in Oakland, Calif. “A lot of people labor under the misapprehension that evolution is anti-religious.” The booklet’s authors try to dispel this misconception by quoting notable scientists who say they have no trouble maintaining their faith (and accepting evolution) and a bevy of religious leaders, including the late Pope John Paul II, who accept evolution. “Religion and science can — and do — coexist,” said co-author Gilbert Omenn, a professor of medicine, genetics and public health at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, at a press conference on Jan. 4. “It’s unfortunate that some parties try to generate conflict where there need not be any.”

This conflict was the impetus behind the original edition of the booklet, which was published in 1984 in response to several state laws requiring that creationism be taught alongside evolution. But the new edition is aimed at anyone curious about evolution — a wider audience than the policymakers, lawyers and teachers who made use of the previous editions.

“This new volume is an attempt to bring the description of the science of evolution even more up-to-date and to better explain what we know about evolution in ways the public can readily understand,” NAS President Ralph Cicerone said at the press conference. The booklet is available to download for free from the NAS Web site (nationalacademies.org/evolution) or by mail for $12.95.

Although unlikely to persuade diehard fundamentalists, the booklet may help convince “the mushy middle,” the approximately 50 percent of Americans who are unsure about evolution, Branch says. The greatest value of the booklet, however, may simply be that it was published by NAS, says NCSE President Kevin Padian, a professor of integrative biology at the University of California at Berkeley. “It’s important for science agencies, especially those affiliated with the government, to take a strong stand on evolution,” he says. “The authority of the National Academy of Sciences is nothing to sneeze at,” Branch adds.

NAS hopes the booklet does more than just educate the public. “This publication is a tool, but it’s only a very small start in getting scientific societies and scientists mobilized in thinking about how science is taught,” said co-author Bruce Alberts, former NAS president and the new editor-in-chief of Science, at the press conference.

Advising school boards on curriculum and writing and improving textbooks are important ways in which scientists can get involved in education, Padian says, although he notes that not all scientists have the time or inclination to get involved in the controversy of teaching evolution. But among those who do, earth scientists have an especially important role to play, he says. “We don’t need to throw more fruit fly genetics at [creationists]; it doesn’t go anywhere,” Padian says. Instead, he says, carefully outlining the major changes in the fossil record gives people visible proof that evolution has occurred.

Links:

Evolution Resources From the National Academies

National Center for Science Education

Subscribe

Subscribe