|

GEOMEDIA

Check out the latest On the Web links, your connection to earth science friendly Web sites. The popular Geomedia feature is now available by topic.

BOOKS: Deciphering the Roles of Science, Policy and Politics: Q&A With Author Roger Pielke Jr.

BOOKS: World’s Oldest Fossils Shows Fossils Just as You Find Them

ADVERTISING: Stories of Oil: Oil Industry Tries a Hollywood Approach

Deciphering the Roles of Science, Policy and Politics: Q&A With Author Roger Pielke Jr.

Courtesy of Roger Pielke Jr. |

| Roger Pielke Jr. teaches environmental studies and the relationship between science and policy — also the topic of his new book The Honest Broker: Making Sense of Science in Policy and Politics — at the University of Colorado at Boulder. |

When Roger Pielke Jr. was an undergraduate student working at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo., in the 1980s, he often heard scientists say that decision-making would be much more straightforward if only policymakers understood science. Later on, while working on his master’s degree and hanging out with the House Science Committee staff in Washington, D.C., he heard the staffers lament that if only scientists better understood the political world, science and policy would get along much better. These two thoughts left their mark on the young man.

Pielke, now a professor of environmental studies at the Center for Science and Technology Policy Research at the University of Colorado at Boulder, elucidates the often nebulous relationship between science and policy in his new book The Honest Broker: Making Sense of Science in Policy and Politics. He describes four different roles that scientists can play. The “pure scientist” stays out of the policy arena completely. The “science arbiter” answers questions but doesn’t offer advice or an opinion on policy options. In contrast, the “issue advocate” voices an opinion on a particular topic in order to advance his or her own agenda. The “honest broker” presents a host of policy options but doesn’t advocate any one of them.

The Honest Broker is a thought-provoking book that speaks to scientists who seek to play a role in policy and politics and provides a starting point for a debate about the different ways scientists can contribute. Any scientist would benefit from reading this book, as it is an eye-opener about the scientist-policymaking relationship. The book is not suitable for the lay person, however, who probably would have trouble following Pielke’s arguments and models and may, quite frankly, fall asleep during the first few pages.

Pielke spoke with scientist and freelance writer Nicole Branan about the choices scientists have when presenting their research to policymakers and why it is important that they understand these choices.

NB: Do you think that many scientists are unaware of the different roles they can choose to play in policy?

RP: Yes. I have noticed that when you ask scientists to become relevant in policy, many of them immediately become an advocate and say, “Here is what I believe.” That’s almost an instinctive reaction. However, while this advocacy role is important, it’s not the only way that scientists can engage with decision-makers.

NB: Why is it important that scientists choose which role they want to play in science policy?

RP: If scientists engage in the policy process, they have to make a choice whether it’s made explicitly or not, because they can’t assume all four different roles at the same time. The concern that I have is that scientists will say that they are pure scientists or arbitrating a scientific question but they are really advocating a position. And I see that as eating away at the legitimacy and the authority of science, which, I think, is very important for decision-making.

NB: You point out in your book that science has become used increasingly as a tool of politics and that its role in policy has been overshadowed. Can you give an example for that?

RP: Politics is about bargaining, negotiation and compromise. It’s about power and about who gets to decide and who gets to win, but it’s not necessarily about the substance of what it is we ought to do. Policy, on the other hand, is a synonym for decision. In other words, we use politics to make policies.

An example of the political use of science is the part of the climate change debate that focuses on crediting or discrediting certain people who are participating in the debate. That’s the political use of science, but that says absolutely nothing about the policy question, which asks what we ought to be doing with respect to climate change. From where I sit, it doesn’t matter who wins or loses the power game if there are no good options on the table. My concern is that if all the focus is on winning and losing and identifying good guys and bad guys, then science becomes an artifact rather than a tool to help us make good decisions.

NB: Has the government been asking more of the scientific community in recent years than it used to in the past?

RP: Yes, particularly since the early 1990s. Part of that has to do with the fact that budgets are tighter and that there is stronger demand for government accountability. Another reason is that the Cold War was sort of a unifying focus for research and development that no longer exists.

NB: One of the chapters in your book looks at the debate on whether or not to intervene in Iraq, which took place in 2002 and early 2003. How does this debate relate to science in policy?

RP: I wanted to show that these issues of providing advice show up in exactly the same form in different political contexts. Intelligence in foreign policy plays the exact same role in a decision process as science does in environmental policy.

People in the scientific community are very quick to say that an agency like the CIA shouldn’t be advocating certain policies, but we seem to have a much more flexible attitude when it comes to scientists advocating stem cell research, for example. It seems to me that we ought to think carefully about the consistency.

NB: What can scientists learn from the debate about the intervention in Iraq?

RP: One of the most important lessons is that if you are expected to serve as an honest broker and don’t fulfill that role, then you may see your credibility evaporate. The Bush administration lost a lot of public credibility in its intelligence estimates after it had turned out that there were no weapons of mass destruction. I would hate for that to happen in environmental science or biomedical science if scientists go out on an advocacy limb. We don’t want to damage our ability to have science as an important resource for decision-making.

Book review

|

World’s Oldest Fossils By Bruce L. Stinchcomb |

Jo Schaper

World’s Oldest Fossils, a 160-page fully illustrated book, identification and monetary value guide by Bruce L. Stinchcomb, showed up on in my mailbox one week, much to my delight. As its title suggests, it is simply a book about old, old fossils. But it’s one worth having on your bookshelf, especially if you fancy yourself any sort of fossil collector.

Early-era paleontologists have focused so much on the Burgess Shale and other Ediacaran fauna that many of the more common Precambrian and Cambrian fossil varieties such as stromatolites and trilobites have been overlooked. Stinchcomb remedies this omission with this book by focusing on these more neglected creatures.

Over his career, Stinchcomb, a geologist at St. Louis Community College at Florrisant Valley in Ferguson, Mo., has been fascinated by many aspects of geology, but his primary expertise is in fossils. After hearing for many years that Missouri had no dinosaur fossils, he ran across a buried report — no pun intended — about Missouri’s Chronister dinosaur site, and then patiently waited until he could do something about seeing it be properly excavated (which it has been). Stinchcomb’s professional career as a geology and paleontology instructor at a local community college combined with his fine academic credentials and enthusiasm for his subject make him an excellent guide to the world’s oldest fossils. He is clearly an academic who has never lost the spark for fieldwork.

Stinchcomb employs his extensive knowledge, sheer enthusiasm and ability to explain geology in this slick, four-color, profusely illustrated book. He has tackled a somewhat academic topic (Precambrian- and Cambrian-aged fossils) with the enthusiasm of an amateur, but with the precision of a professional. Short blocks of prose introduce each of the 10 chapters to orient the reader to the topics at hand. For example, the Precambrian chapter is really heavy on stromatolites, so it’s good to know what one is.

Stinchcomb includes a “value range” for each of his samples — he understands that fossils have value to both the academic and to the collector — and by including the value range, he helps educate amateurs to the approximate value (in 2007 dollars) of their finds and acquisitions.

The glory of this book is in the 509 photographs. Many fossil field guides show only picture-perfect specimens. But as anyone who has collected fossils knows, that isn’t the real world. A collector is more likely to pick up broken or partially excavated specimens that never show up in the standard field guides. So Stinchcomb includes those “broken” photos as well as showcase examples. For example, some photos show just the cephalon (head piece) or pygidium (tail piece) of trilobites — these disarticulated parts are often what collectors find in the field.

The book assumes a general familiarity with fossils, but does not require an extensive background. The extended photo captions contain most of the information about the fossils, rather than pages upon pages of dry, thick prose common in paleontology books. It’s not quite a field guide, nor is it quite a textbook. Being reasonably priced makes it a good addition to one’s book collection, where it bridges the gap between a beginner’s guide and a professional reference.

Stories of Oil: Oil Industry Tries a Hollywood Approach

API |

| Earlier this year, the American Petroleum Institute, an oil and gas industry trade group, launched a new ad campaign that the organization hopes will improve the industry’s image, both with the public and in Congress. |

Somewhere in Southeast Asia, a man sits in a small crowd, watching a shadow puppet play. As a warrior shadow slays a dragon shadow, the man doodles snakelike dragons on a sketchpad, clearly lost in thought.

This is the moody opening scene of Shell Oil’s nine-minute advertisement/film called Eureka, part of its Real Energy global communications campaign that is intended to promote goodwill and a more “green” outlook from the company by telling human stories of Shell employees engaging in creative problem-solving. The film, snippets of which ran as television ads earlier this year, appears in its full-length version on Shell’s Web site (www.shell.com/realenergy) and was also included as a DVD insert in magazines such as Wired, Popular Science and National Geographic. It is well-made, playing more like a professional documentary than an ad. It tells the compelling true story of Shell oil engineer Jaap van Ballegooijen, who was struggling to find a way to drill seemingly undrillable pockets of oil in offshore sites such as Shell’s Champion West field in Brunei. “We’d have to build thousands of other platforms just to reach them,” he tells a reporter in the film who has shown up to interrogate him. “Economically and environmentally, that’s just not acceptable.”

Complicating this puzzle is the engineer’s strained relationship with his teenage son back in Amsterdam. This seemingly unrelated subplot is not just taking the film’s Hollywood aesthetic to an extreme, but instead it ultimately leads to a reconciliation scene between father and son involving milkshakes and bendy-straws — the latter of which suddenly inspires van Ballegooijen to conceive of a new kind of drill. (He later tells an audience of Shell executives that he considered calling it a “bendy-straw” drill). The “snake wells” created by this drill are now in use in Shell’s West Oil Field in Brunei, the film tells us, and that technology is now helping to prolong the life of oilfields across the world. In an accompanying “making-of” film on Shell’s Web site, the film’s producers say that they wanted to talk about the company’s innovations by telling a rich human story, not “a simple sound bite.”

Although no other companies have yet produced such long film/ads, Shell isn’t the only company in the energy industry embarking on a softer, more creative approach to improving its image. According to a Nov. 9, 2006, article in The Wall Street Journal, the senior vice president of the marketing research firm Harris Interactive, Inc., Jean Statler, told executives at a petroleum industry meeting in late October 2006 that the oil industry’s image is “in a free-fall” and that “things are really as low as they’ve been in a long time — maybe ever.” Early this year, the American Petroleum Institute (API), an oil and gas industry trade group in Washington, D.C., launched a multimillion-dollar print, radio and television ad campaign that Harris Interactive is masterminding.

The ads, created by advertising company Blue Worldwide, the advertising division of the public relations firm Edelman, are API’s “way of really getting the facts out there and being part of the [energy] dialogue,” says Erin Thomson, director of communications at API. The ads are intended to persuade policymakers that the narrowing gap between supply and demand is to blame for rising prices, not oil industry collusion or price-fixing. They also advise against raising taxes on oil companies and suggest that policymakers allow for drilling in currently off-limit regions, such as offshore and in the Arctic.

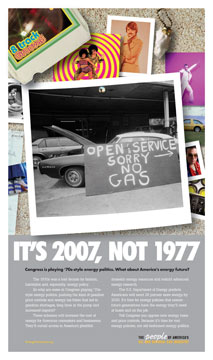

However, the ads take a more subtle approach to these topics, focusing on such family-friendly slants as ensuring that energy needs for future generations will be met, as well as on new, “greener” fuels and technologies, such as ultra-low-sulfur diesel (one ad reads: “Think 18-wheel air freshener”). Another ad focuses on a message that API executives have repeatedly relayed to Congress this year — fears of a return to the long gas lines of the 1970s — with a TV spot that drives the point home using 1970s-era graphics and groovy disco-ish background music.

Chevron Corporation also launched its own advertising campaign in late September, hiring a Hollywood cinematographer to film a series of television ads that will air around the world in eight different languages. Like Shell’s film, Chevron’s ads take a softer, human approach, focusing on its employees’ efforts at problem-solving and the message that fossil fuels are necessary to the world’s energy supply, even as companies explore alternative fuel options. “At Chevron, ‘human energy’ captures our positive spirit in delivering energy to a rapidly changing world,” said Rhonda Zygocki, Chevron vice president of Policy, Government and Public Affairs, in a Sept. 28 Chevron press release.

Whether such kinder, gentler ad campaigns will ultimately help change public perception of the petroleum industry remains to be seen. It has worked before: Harris Interactive has, in the past, also helped to redefine the image of embattled products from plastics to milk (“Got milk?”), according to the Journal. Evidence of the petroleum ads’ impact so far is still scanty — “I can tell you anecdotally that [the 1970s ad], for example, is one we tend to get more calls on,” Thomson says. “It’s a funny and humorous way of grabbing people’s attention.” And in the long run, it may be that these ads will provide the oil industry with a breath of fresh air.

Links:

www.shell.com/realenergy

Subscribe

Subscribe