Geotimes

Untitled Document

Web Extra

Thursday, October 14, 2004

Mount St. Helens activity updates

Web

Extra Thursday, October 14, 2004

Mount

St. Helens grows new lava dome

Mount

St. Helens grows new lava dome

"I want to remind everyone that we are still dealing with a restless volcano,"

said Tina Neal, a geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in a daily

press conference on Oct. 13. Mount St. Helens in Washington remains at a level

2 advisory, which means that there is a significant chance of hazardous volcanic

activity, but geologists do not believe a "life- or property-threatening

event" is imminent.

Mount St. Helens has been growing a new

lava dome on the south side of the old one, which grew from 1980 through 1986.

In the night sky, it can be seen glowing red from a number of vantage points.

Temperatures have measured close to 700 degrees Celsius on the new growth. All

photos courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey.

In the weeks since Mount St. Helens first began shaking to life with thousands

of tiny earthquakes, seismic activity has waxed and waned before and following

large steam-and-ash eruptions. Since Oct. 6, however, seismic activity has remained

at low levels, with low-frequency events that are consistent with the intrusion

of gas and magma just below the surface.

One

of the more interesting things geologists have been watching is the growth of

a new lava dome on the south side of the existing lava dome, which grew from

1980 through 1986, the last time a major eruption occurred on the volcano. New

lava is glowing red at the surface of the new and still-growing fin-shaped dome,

and temperatures of the rock have been measured as high as 690 degrees Celsius.

One

of the more interesting things geologists have been watching is the growth of

a new lava dome on the south side of the existing lava dome, which grew from

1980 through 1986, the last time a major eruption occurred on the volcano. New

lava is glowing red at the surface of the new and still-growing fin-shaped dome,

and temperatures of the rock have been measured as high as 690 degrees Celsius.

Researchers have not yet figured out how large the new dome is, but preliminary

measurements suggest it has grown more than 400 feet over the past two weeks.

If new lava continues to escape and build the dome, it could easily dwarf the

old lava dome, Neal said. The lava dome growth is as expected with the extrusion

of magma, Neal said, and incandescence, including a rosy glow in the sky at

night, will continue to be viewable as weather permits.

New growth of a lava dome in the crater

on Mount St. Helens can be seen on the upper side of an existing lava dome.

Steam continues to leak from cracks on the dome.

GPS instruments at various points on the volcano have recorded little deformation

outside of the dome. Thus, the chance of a cataclysmic eruption such as what

occurred in 1980 is highly unlikely. Before that eruption, the northern flank

was deforming several feet per day.

Over the past few days, USGS has deployed a new suite of instruments on the

volcano, Neal said, including a seismometer, tilt-meters and new GPS instruments

to measure the growth and expansion of the dome, and microphones to record sounds

of explosions or gas releases. "We're still figuring out what's coming

in," Neal said, but they expect to have new results every day. Additionally,

when weather permits, geologists are making daily flights over the crater to

measure gas and thermal levels.

The probability of an endangering eruption is significantly less than at any

time since Oct. 2 when the alert level was raised, USGS said. Geologists caution,

however, that escalation in unrest and even an eruption could occur suddenly

and without warning. Steam-and-ash eruptions as well as growth of the lava dome

will likely continue for weeks to months.

Megan Sever

Links:

Seattle

Times coverage

Mount

St. Helens VolcanoCam

U.S.

Geological Survey Cascades Volcano Observatory

Back to top

Untitled Document

Web

Extra Wednesday, October 6, 2004

Mount St. Helens alert level

lowered: activity continues

On

Oct. 6, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) lowered the alert level for Mount

St. Helens in Washington from a Level 3 Volcano Alert to a Level 2 Volcano Advisory,

in response to lowered seismicity since the previous day's steam-and-ash eruption.

Geologist Willie Scott said the scientists no longer believe that an eruption

is imminent.

On

Oct. 6, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) lowered the alert level for Mount

St. Helens in Washington from a Level 3 Volcano Alert to a Level 2 Volcano Advisory,

in response to lowered seismicity since the previous day's steam-and-ash eruption.

Geologist Willie Scott said the scientists no longer believe that an eruption

is imminent.

A Volcano Advisory indicates that "processes are underway that have significant

likelihood of culminating in hazardous volcanic activity" but the evidence

does not indicate that a "life- or property-threatening event is imminent."

According to USGS, seismic activity Tuesday and Wednesday has been at "very

low levels," with individual earthquakes being "rare." Scientists

observed weakened steam emissions from the crater, and suggested that a lack

of rockfall and earthquake signals indicate that deformation of the uplift area

has slowed. The area had uplifted more than 100 feet since activity began last

week.

Mount St. Helens explosively erupted

ash and steam again on Tuesday, sending the mixture several thousand feet above

the crater rim and blanketing nearby towns with a thin layer of ash. Since this

explosion, however, activity has quiesced, leading U.S. Geological Survey geologists

to lower the alert level. Photo courtesy of USGS.

The scientists said that the probability of an endangering eruption is significantly

less than at any time since Saturday when the alert level was raised. They caution,

however, that escalation in unrest and even an eruption could occur suddenly

and without warning. Steam-and-ash eruptions will likely continue for weeks

to months.

Geologists will continue to monitor the volcano to see what happens next.

Megan Sever

Links:

Article

on MSNBC.com

Seattle

Times coverage

Mount

St. Helens VolcanoCam

U.S.

Geological Survey Cascades Volcano Observatory

Past related Geotimes stories:

"Paths

of Destruction: The Hidden Threat at Mount Rainier," April 2004

"Mount

St. Helens 20 Years Later: What We've Learned," May 2000

Back to top

Web

Extra Friday, October 1, 2004 Updated

October 4

Mount

St. Helens erupts steam and ash

Mount

St. Helens erupts steam and ash

More than a week after seismic activity began, Mount St. Helens in Washington

erupted on Friday afternoon with a thick plume of white steam and light ash.

Since then, additional steam-and-ash emissions have occurred and will likely

continue, prompting officials on Saturday to raise the alert level to Volcano

Alert, which is the highest level and indicates that an eruption could be imminent.

Aviation warnings are at color-code Red, also the highest level. Parts of the

surrounding area, including the Johnston Ridge Observatory, have been evacuated

as a precaution.

Mount St. Helens has erupted several

times since its initial steam-and-ash eruption on Friday, pictured here. Geologists

are constantly monitoring the volcano for signs of further activity. All photos

courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey.

Although seismicity quieted down at first after Friday's 24-minute eruption,

it picked back up again within a few hours, with small earthquakes (maximum

magnitude-3.0) occurring at rates of one to two per minute. The next day, the

volcano had another small eruption of steam and ash. After yet another small

eruption on Sunday night, the volcano awoke on Monday morning with two eruptive

events.

Monday's

events, however, are different from the previous few days' steam-and-ash eruptions,

said geologist Willie Scott in a press conference held by the U.S. Geological

Survey's Cascades Volcano Observatory. Two eruptive clouds, which looks to be

predominantly, if not all, steam, rose several thousand feet above the summit

of Mount St. Helens, but were not accompanied by seismic signals or waves that

indicate movement, he said. Instead, the steam events indicate that magma or

gas must have moved close to the surface and to the glacier, and have basically

started "boiling the glacier" to produce steam. Hot gases from the

volcano may have vaporized ice and snow contained in the glacier in the summit

crater to produce the steam eruption. Background earthquakes have continued

at the same rate as occurred with the other eruptions, but there was no onset

of larger earthquakes such as occurred prior to the steam-and-ash eruptions

on Friday, Saturday and Sunday.

Monday's

events, however, are different from the previous few days' steam-and-ash eruptions,

said geologist Willie Scott in a press conference held by the U.S. Geological

Survey's Cascades Volcano Observatory. Two eruptive clouds, which looks to be

predominantly, if not all, steam, rose several thousand feet above the summit

of Mount St. Helens, but were not accompanied by seismic signals or waves that

indicate movement, he said. Instead, the steam events indicate that magma or

gas must have moved close to the surface and to the glacier, and have basically

started "boiling the glacier" to produce steam. Hot gases from the

volcano may have vaporized ice and snow contained in the glacier in the summit

crater to produce the steam eruption. Background earthquakes have continued

at the same rate as occurred with the other eruptions, but there was no onset

of larger earthquakes such as occurred prior to the steam-and-ash eruptions

on Friday, Saturday and Sunday.

Friday's eruption at Mount St. Helens

was both ash and steam, as seen here. Monday's eruptions were predominantly

steam, indicating that magma is rising toward the surface.

"This is pretty good evidence that we have something very hot near the

surface," Scott said, but it does not indicate any greater or less likelihood

that a magma eruption will occur soon. Scientists are monitoring the volcano

by taking thermal images of the dome and the crater, flying over the volcano

to measure the gases being released and monitoring GPS instruments for ground

deformation. But, Scott said, it is likely the volcano will "go without

any warning at all." If that occurred, the eruption would be rich in ash

that could reach 50,000 feet in altitude, and would produce lava and last tens

of minutes to hours. He said the scientists will be looking for all possible

indications that something bigger is about to occur, but "all options are

open right now. It's best just to watch and see what happens."

One

interesting thing to note, Scott said, is that the lava dome around the glacier

has seen intense deformation over the past few days — around 100 feet.

Furthermore, new cracks have popped up on the dome and in the glacier —

all indications that "somewhere down the line, we [can] expect an explosive

eruption." The cracks might lead to a greater likelihood of a larger, magma

and ash-rich eruption, Scott said, because the magma would have more escape

options. All of the events so far, he said, have been "expectable."

One

interesting thing to note, Scott said, is that the lava dome around the glacier

has seen intense deformation over the past few days — around 100 feet.

Furthermore, new cracks have popped up on the dome and in the glacier —

all indications that "somewhere down the line, we [can] expect an explosive

eruption." The cracks might lead to a greater likelihood of a larger, magma

and ash-rich eruption, Scott said, because the magma would have more escape

options. All of the events so far, he said, have been "expectable."

The lava dome atop Mount St. Helens

has been growing and deforming significantly since activity began there last

week. It has deformed more than 100 feet, according to USGS geologists.

Indeed, "this is pretty much exactly what we expected to happen,"

says Jim Vallance, a geologist at CVO. From 1981 to 1986, "we saw a lot

of events like this," in which steam and ash erupted and quiesced. The

last eruption of Mount St. Helens was in 1986, six years after the major eruption

on May 18, 1980, that blasted away the entire top and northwest face of the

mountain releasing 24 megatons of thermal energy.

Geologists are continuing to monitor the volcano to see what happens next.

Last updated at 4:00 p.m. EDT, Oct. 4, 2004.

Megan Sever

Links:

Article

on MSNBC.com

Seattle

Times coverage

Mount

St. Helens VolcanoCam

U.S.

Geological Survey Cascades Volcano Observatory

Past related Geotimes stories:

"Paths

of Destruction: The Hidden Threat at Mount Rainier," April 2004

"Mount

St. Helens 20 Years Later: What We've Learned," May 2000

Back to top

Untitled Document

Web

Extra Friday, October 1, 2004

Mount St. Helens could

erupt in days to months

In the

next few days to a month, there's a 70 percent chance that a small to moderate

eruption event will happen at Mount St. Helens, site of the violent and deadly

eruption of May 18, 1980, according to an announcement yesterday by researchers

at the U.S. Geological Survey's (USGS) David A. Johnston Cascades Volcano Observatory

(CVO), in Vancouver, Wash.

In the

next few days to a month, there's a 70 percent chance that a small to moderate

eruption event will happen at Mount St. Helens, site of the violent and deadly

eruption of May 18, 1980, according to an announcement yesterday by researchers

at the U.S. Geological Survey's (USGS) David A. Johnston Cascades Volcano Observatory

(CVO), in Vancouver, Wash.

"But that also means there's a 1 in 3 chance that nothing is going to happen,"

said Cynthia Gardner, a CVO geologist, at Thursday's press conference. "That

word has to get out too."

Scientists now say that Mount St. Helens

in Washington State, the most active volcano in the Cascade Range, has a 70

percent chance of erupting in the next few days to a month. Shown here is an

oblique aerial photograph of the north flank, crater, lava dome and new glacier

(behind dome). U.S. Geological Survey photo taken on Sept. 26 by John S. Pallister.

Based on models of other volcanic events, researchers say that the event could

possibly include any or all of the following: further build-up of the lava dome,

which formed in the crater between 1980 and 1986; possible lava flows outside

the crater, explosive eruption with ballistic rock fragments (from inch to fist-sized)

that could be flung up to 3 miles outside the crater; and an ash plume ejected

to an altitude of hundreds of feet to 20,000 or 30,000 feet. Researchers said

that the latter is the main concern, as it would be hazardous for aircraft.

Gardner said CVO is working with the National Weather Service regarding wind

forecasts.

The Johnston

Ridge Observatory Visitor's Center, 5 miles away, is the nearest structure to

the volcano. It remains open and, according to Roger Peterson of the U.S. Forest

Service, has been drawing crowds of 150 to 1,000 onlookers a day to gaze into

the amphitheater-shaped breach of the northwest flank left by the devastating

May 1980 eruption. All trails and backcountry campsites in Gifford Pinchot National

Forest, which contains the mountain, however, have been closed, Peterson added.

The Johnston

Ridge Observatory Visitor's Center, 5 miles away, is the nearest structure to

the volcano. It remains open and, according to Roger Peterson of the U.S. Forest

Service, has been drawing crowds of 150 to 1,000 onlookers a day to gaze into

the amphitheater-shaped breach of the northwest flank left by the devastating

May 1980 eruption. All trails and backcountry campsites in Gifford Pinchot National

Forest, which contains the mountain, however, have been closed, Peterson added.

Throughout the week seismicity has been "ramping up, and plateauing"

repeatedly, Gardner said, at the highest level since 1998. It started last Thursday,

Sept. 23, with an outbreak of small, shallow earthquakes. On Sunday, researchers

set the alert level to level one — Notice of Volcanic Unrest. Activity

then increased such that by Wednesday they raised the alert level to level two

— a Volcano Advisory, which is issued when "monitoring and evaluation

indicate that processes are underway that have significant likelihood of culminating

in hazardous volcanic activity but when the evidence does not indicate that

a life- or property-threatening event is imminent."

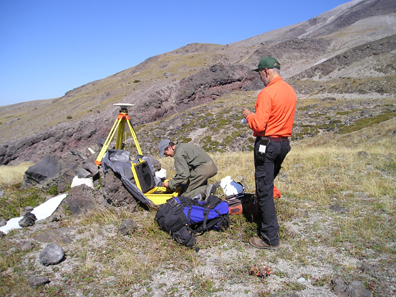

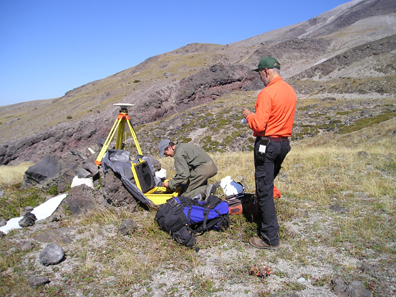

A U.S. Geological Survey scientist stands on the West Ridge of Mount St. Helens

this past Tuesday — one of many volcanologists watching the volcano and

trying to undertsand its current activity. USGS photo taken by Mike Poland and

Dan Dzurisin.

As of Thursday afternoon, seismologists at CVO and the University of Washington's

Pacific Northwest Seismograph Network were recording three to four small earthquakes

per minute with magnitudes increasing, from less than 2.0 earlier in the week,

to as large as a 3.3 on Thursday morning. Larger magnitude quakes in the range

of 3.0 to 3.3 were happening every three to four minutes.

Researchers

said that the increased frequency and magnitude of the seismicity indicates

potential magma involvement under the lava dome. "Our hypothesis now is

that there is some magma involved but that that magma is largely degassed,"

Gardner said.

Researchers

said that the increased frequency and magnitude of the seismicity indicates

potential magma involvement under the lava dome. "Our hypothesis now is

that there is some magma involved but that that magma is largely degassed,"

Gardner said.

According to Bill Steele, information director at the University of Washington's

Pacific Northwest Seismograph Network, researchers previously suspected the

movement of steam or water below the lava dome to be causing earthquakes. This

idea was based on lower magnitude and frequency of the quakes, the absence of

magmatic gases (such as carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide and hydrogen sulfide)

in the air above the crater, and the fact that the Northwest experienced an

unusually rainy and wet August.

U.S. Geological Survey scientists set up a GPS unit on the flanks of Mount St.

Helens, north of Butte Camp, to help better monitor its recent activity. USGS

photo taken on Sept. 28 by Mike Poland and Dan Dzurisin.

"With steam, we would have expected fracturing and one to one and a half

days of activity," Gardner said, "but certainly not five or six days.

[Steam] may be part of the equation but not all."

Three flights this week over the crater have so far detected no magmatic gases.

Degassed magma would create a much less explosive eruption, while gaseous, volatile

magma would create a much more violent eruption. The scientists said that they

plan to use thermal imaging technology today to determine the temperature of

the lava dome, which will be a better indicator of the presence or absence of

magma.

Early in the week, researchers detected about 1.5 inches of deformation on the

lava dome using a GPS monitor. Additional monitors are on the lip of the crater

and the flanks of the volcano. No deformation has yet been detected on the flanks,

which would be an indication of deeper activity, Gardner said. Prior to the

1980 eruption, the north flank of the volcano bulged outward nearly 450 feet.

For safety reasons, geologists are no longer hiking into the crater; however,

data from the most critical GPS sensors can be collected remotely.

Researchers emphasized they expect nothing like the cataclysmic eruption of

May 18, 1980, that blasted away the entire top and northwest face of the mountain

releasing 24 megatons of thermal energy, ejecting ash and debris 80,000 feet

into the air, and lowering the summit elevation by more than 1,300 feet. The

resulting pyroclastic flows, landslides, and lahars (mudflows) were some of

the largest in recorded history. The eruption claimed the lives of 57 people,

including 30-year-old USGS volcanologist David A. Johnston, who was monitoring

the volcano that morning from the ridge that now bears his name.

Sara Pratt

Geotimes contributing writer

Naomi Lubick contributed to this report.

Links:

Mount

St. Helens VolcanoCam

U.S.

Geological Survey Cascades Volcano Observatory

Past related Geotimes stories:

"Paths

of Destruction: The Hidden Threat at Mount Rainier," April 2004

"Mount

St. Helens 20 Years Later: What We've Learned," May 2000

Back to top

Untitled Document

Mount

St. Helens grows new lava dome, Oct.

14

Mount

St. Helens grows new lava dome, Oct.

14

Mount

St. Helens grows new lava dome

Mount

St. Helens grows new lava dome

One

of the more interesting things geologists have been watching is the growth of

a new lava dome on the south side of the existing lava dome, which grew from

1980 through 1986, the last time a major eruption occurred on the volcano. New

lava is glowing red at the surface of the new and still-growing fin-shaped dome,

and temperatures of the rock have been measured as high as 690 degrees Celsius.

One

of the more interesting things geologists have been watching is the growth of

a new lava dome on the south side of the existing lava dome, which grew from

1980 through 1986, the last time a major eruption occurred on the volcano. New

lava is glowing red at the surface of the new and still-growing fin-shaped dome,

and temperatures of the rock have been measured as high as 690 degrees Celsius.

On

Oct. 6, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) lowered the alert level for Mount

St. Helens in Washington from a Level 3 Volcano Alert to a Level 2 Volcano Advisory,

in response to lowered seismicity since the previous day's steam-and-ash eruption.

Geologist Willie Scott said the scientists no longer believe that an eruption

is imminent.

On

Oct. 6, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) lowered the alert level for Mount

St. Helens in Washington from a Level 3 Volcano Alert to a Level 2 Volcano Advisory,

in response to lowered seismicity since the previous day's steam-and-ash eruption.

Geologist Willie Scott said the scientists no longer believe that an eruption

is imminent.  Mount

St. Helens erupts steam and ash

Mount

St. Helens erupts steam and ash  Monday's

events, however, are different from the previous few days' steam-and-ash eruptions,

said geologist Willie Scott in a press conference held by the U.S. Geological

Survey's Cascades Volcano Observatory. Two eruptive clouds, which looks to be

predominantly, if not all, steam, rose several thousand feet above the summit

of Mount St. Helens, but were not accompanied by seismic signals or waves that

indicate movement, he said. Instead, the steam events indicate that magma or

gas must have moved close to the surface and to the glacier, and have basically

started "boiling the glacier" to produce steam. Hot gases from the

volcano may have vaporized ice and snow contained in the glacier in the summit

crater to produce the steam eruption. Background earthquakes have continued

at the same rate as occurred with the other eruptions, but there was no onset

of larger earthquakes such as occurred prior to the steam-and-ash eruptions

on Friday, Saturday and Sunday.

Monday's

events, however, are different from the previous few days' steam-and-ash eruptions,

said geologist Willie Scott in a press conference held by the U.S. Geological

Survey's Cascades Volcano Observatory. Two eruptive clouds, which looks to be

predominantly, if not all, steam, rose several thousand feet above the summit

of Mount St. Helens, but were not accompanied by seismic signals or waves that

indicate movement, he said. Instead, the steam events indicate that magma or

gas must have moved close to the surface and to the glacier, and have basically

started "boiling the glacier" to produce steam. Hot gases from the

volcano may have vaporized ice and snow contained in the glacier in the summit

crater to produce the steam eruption. Background earthquakes have continued

at the same rate as occurred with the other eruptions, but there was no onset

of larger earthquakes such as occurred prior to the steam-and-ash eruptions

on Friday, Saturday and Sunday.  One

interesting thing to note, Scott said, is that the lava dome around the glacier

has seen intense deformation over the past few days — around 100 feet.

Furthermore, new cracks have popped up on the dome and in the glacier —

all indications that "somewhere down the line, we [can] expect an explosive

eruption." The cracks might lead to a greater likelihood of a larger, magma

and ash-rich eruption, Scott said, because the magma would have more escape

options. All of the events so far, he said, have been "expectable."

One

interesting thing to note, Scott said, is that the lava dome around the glacier

has seen intense deformation over the past few days — around 100 feet.

Furthermore, new cracks have popped up on the dome and in the glacier —

all indications that "somewhere down the line, we [can] expect an explosive

eruption." The cracks might lead to a greater likelihood of a larger, magma

and ash-rich eruption, Scott said, because the magma would have more escape

options. All of the events so far, he said, have been "expectable."

In the

next few days to a month, there's a 70 percent chance that a small to moderate

eruption event will happen at Mount St. Helens, site of the violent and deadly

eruption of May 18, 1980, according to an announcement yesterday by researchers

at the U.S. Geological Survey's (USGS) David A. Johnston Cascades Volcano Observatory

(CVO), in Vancouver, Wash.

In the

next few days to a month, there's a 70 percent chance that a small to moderate

eruption event will happen at Mount St. Helens, site of the violent and deadly

eruption of May 18, 1980, according to an announcement yesterday by researchers

at the U.S. Geological Survey's (USGS) David A. Johnston Cascades Volcano Observatory

(CVO), in Vancouver, Wash. The Johnston

Ridge Observatory Visitor's Center, 5 miles away, is the nearest structure to

the volcano. It remains open and, according to Roger Peterson of the U.S. Forest

Service, has been drawing crowds of 150 to 1,000 onlookers a day to gaze into

the amphitheater-shaped breach of the northwest flank left by the devastating

May 1980 eruption. All trails and backcountry campsites in Gifford Pinchot National

Forest, which contains the mountain, however, have been closed, Peterson added.

The Johnston

Ridge Observatory Visitor's Center, 5 miles away, is the nearest structure to

the volcano. It remains open and, according to Roger Peterson of the U.S. Forest

Service, has been drawing crowds of 150 to 1,000 onlookers a day to gaze into

the amphitheater-shaped breach of the northwest flank left by the devastating

May 1980 eruption. All trails and backcountry campsites in Gifford Pinchot National

Forest, which contains the mountain, however, have been closed, Peterson added.

Researchers

said that the increased frequency and magnitude of the seismicity indicates

potential magma involvement under the lava dome. "Our hypothesis now is

that there is some magma involved but that that magma is largely degassed,"

Gardner said.

Researchers

said that the increased frequency and magnitude of the seismicity indicates

potential magma involvement under the lava dome. "Our hypothesis now is

that there is some magma involved but that that magma is largely degassed,"

Gardner said.