Geotimes

Untitled Document

Feature

The Geoscience

vote

Geotimes Staff

In a Geotimes online

poll, run during August and September, 60 percent of you said that geoscience

topics, including energy and land-use policy, are major factors in your choice

for president. Here, we offer some status reports and updates on some of those

geoscience-related policies — from oil and gas drilling in Alaska to funding

the space program. Interspersed throughout is information we compiled secondhand

on the major presidential candidates’ viewpoints.

In June, we sent the Bush and Kerry campaigns 20

questions on key geoscience issues. And while both campaigns agreed to answer

the questions, two months later, neither side had answered the questions, despite

several follow-ups. Perhaps this is a sign of the times — candidates have

too little time and bigger fish to fry — or perhaps it says something about

how seriously these policy-makers view earth science issues.

Slippery slope for

drilling in Alaska

Managing Federal lands

The evolving debate over teaching evolution

Funding and the fate of NASA

Climate tipping point

Clean air deadlock

Web exclusive: Water worries

Additional links

Slippery

slope for drilling in Alaska

In the 36

years since the discovery of oil at Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, environmentalists and

the petroleum industry have argued over how much federally owned land on the

North Slope, if any, should be opened for oil and gas exploration. The debate

has left policy-makers trying to weigh the potential gain of extracting petroleum

against the environmental impact of drilling in a relatively pristine ecosystem.

In the 36

years since the discovery of oil at Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, environmentalists and

the petroleum industry have argued over how much federally owned land on the

North Slope, if any, should be opened for oil and gas exploration. The debate

has left policy-makers trying to weigh the potential gain of extracting petroleum

against the environmental impact of drilling in a relatively pristine ecosystem.

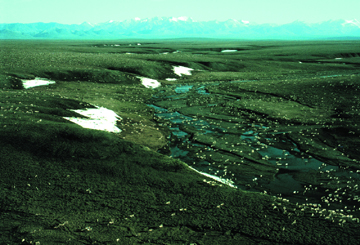

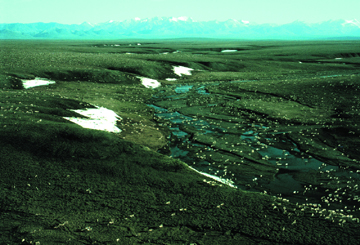

Politicians continue to debate oil and

gas drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, which is home to caribou

and other Arctic species. Image courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The upcoming presidential election could have a large impact on the central

point of that debate — the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), 19 million

acres of northeast Alaska that Congress set aside in 1980 to conserve habitat

for caribou, musk ox and other Arctic species. In section 1002 of the conservation

act, Congress postponed a decision about future management of the 1.5-million-acre

coastal plain region (the so-called 1002 area), which geologists believe holds

valuable oil and gas resources, but which is also part of the calving grounds

of the Porcupine caribou herd.

Despite recent attempts by Congress and the White House, measures to open ANWR

to drilling have continually been defeated in the Senate, where Democratic presidential

candidate Sen. John Kerry (D-Mass.), among others, has voted against them. The

most recent measure, taken up last June, tied the opening of the refuge to health

benefits for retired miners in an effort to gain the support of coal mining

states. Congress dropped the proposal after the miners’ union rejected

it, but the debate over ANWR is far from over.

“It’s never off the table,” says Judy Brady, executive director

of the Alaska Oil and Gas Association. “As long as this country needs oil,

ANWR’s never going to be off the table.”

| Kerry Vs. Bush: Energy Policy |

| In addition to disagreeing on whether

or not to drill for oil and gas on federal lands on Alaska’s North

Slope, the two leading presidential candidates propose different approaches

to meeting the nation’s energy needs. For more on some of their proposals

on alternative energy, see below. |

| KERRY |

BUSH |

| Encourages cooperation between the United States, Canada and Mexico to

expand North American energy supplies |

Supports increased domestic oil and gas production, including on federal

and tribal lands |

| Agrees with construction of a natural gas pipeline extending from Alaska

to the lower 48 states |

Wants to authorize construction of a natural gas pipeline from Alaska

to the lower 48 states |

| Opposes opening the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil and gas exploration |

Favors opening the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil and gas exploration |

| Wants to suspend filling the Strategic Petroleum Reserve until prices

return to normal |

Supports filling the Strategic Petroleum Reserve to reduce dependence

on foreign oil sources |

According to the Energy Information Administration, the United States uses

about 20 million barrels of petroleum a day, or about 7.3 billion barrels a

year, more than half of which is imported. A 1998 U.S. Geological Survey (USGS)

petroleum assessment of the 1002 area of ANWR reported between 4.3 billion and

11.8 billion barrels of technically recoverable oil on federal lands. The amount

that is economically recoverable, however, depends on many factors, including

exploration, production and pipeline costs, as well as the market rate of a

barrel of oil.

Proponents of drilling ANWR maintain that it could alleviate the nation’s

dependence on foreign oil, while opponents maintain that the cost to the environment

is too high and that too little oil will be recovered to impact the country’s

petroleum needs. “The United States has only 3 percent of the world’s

proven oil reserves, and we use 25 percent of the world’s produced oil,”

says Charles Clusen, Alaska project director for the Natural Resources Defense

Council. “We can’t drill our way to oil independence.”

While both presidential candidates agree that the country needs to decrease

its dependence on foreign oil, they have different ideas about how to do it.

Bush’s energy plan focuses on increasing the country’s energy supply

by encouraging domestic production through various means, including opening

ANWR to drilling and building new oil refineries. Kerry’s energy plan focuses

on conservation, tax incentives for fuel-efficient cars and supporting the development

of alternative fuels such as ethanol from agricultural waste.

Although ANWR is inaccessible for now, new oil and gas development is proceeding

in other regions of the North Slope, initiated by the recent discoveries of

some productive wells and, possibly, by the lack of progress with ANWR. “I

think the companies have given up on getting access to ANWR. They basically

are looking in other areas, not counting on ANWR being opened up,” says

geologist Ken Bird, project leader for USGS’s Alaska Petroleum Studies

Project and co-author of a 2002 petroleum assessment of the National Petroleum

Reserve-Alaska (NPRA).

According to the report, federal lands in the 23-million-acre tract west of

Prudhoe Bay may hold between 5.9 billion and 13.2 billion barrels of technically

recoverable oil. NPRA was set aside in 1923 by President Warren G. Harding as

a petroleum reserve for the U.S. Navy.

The discovery in 1994 of the Alpine oilfield from reservoir rocks that trend

westward across the border and into NPRA has renewed interest in the region.

Since then, NPRA lease sales, the first in 20 years, have resulted in discoveries

in the northeast section in 2001 and 2002. Most recently, the Bureau of Land

Management held a lease sale on 5 million acres of the northwest section of

NPRA last June (see Geotimes,

July 2004).

According to Brady of the Alaska Oil and Gas Association, neither the NPRA lease

sales nor a proposed natural gas pipeline project are expected to be affected

much by the outcome of the November election; however, the eventual fate of

ANWR’s 1002 area could be. “There is some concern, for instance, that

if a Democratic candidate won,” she says, “that portion of ANWR that’s

supposed to be open for oil and gas could be made into a wilderness area.”

Sara Pratt

Geotimes contributing writer

Links:

"Two suits on land

use," Geotimes, July 2004

"A

fresh angle on oil drilling," Geotimes, March 2004

"The drilling footprint

on the North Slope," Geotimes, May 2003

"Caribou study

charges energy debate," Geotimes, June 2002

Back to top

Managing

Federal lands

The U.S. federal

government manages 454 million acres of land, about 20 percent of the country’s

landmass, with most of this acreage in the West. Over the past year, debate over

management of federal lands has intensified, with topics such as oil and gas exploration

and production, wildfire protection and most recently the Bush administration’s

revision of the “roadless rule” entering the political spotlight.

The U.S. federal

government manages 454 million acres of land, about 20 percent of the country’s

landmass, with most of this acreage in the West. Over the past year, debate over

management of federal lands has intensified, with topics such as oil and gas exploration

and production, wildfire protection and most recently the Bush administration’s

revision of the “roadless rule” entering the political spotlight.

A new rule that gives the decision-making

for road building to state governors could affect exploration and development

of federal lands in roadless areas outside of Grand Teton National Park, pictured

here, for example. Photo courtesy of National Park Service.

Included in those broad topics are several issues that will continue to face the

federal government no matter who takes office next year, says Gary Brewer, director

of the Environmental Management Center at Yale’s School of Forestry, from

liquid natural gas pipelines in offshore protected areas, such as the Florida

Keys National Marine Sanctuary (see Geotimes,

July 2004), to leasing in Wyoming for natural gas drilling (at issue in the

courts). “The geology is all the same,” he says, but “the politics

never seem to get resolved.”

Indeed, the debate over road building on national forest land has been around

since before the Clinton administration banned road building and logging on about

58.5 million acres on Jan. 12, 2001. Under development since 1999, the Roadless

Areas Initiative received at least a million public comments, of which only a

small percentage were negative. Postponed at first by the Bush administration

and, following several lawsuits, the rules eventually took effect on a temporary

basis in the intended wilderness areas, except for the Tongass National Forest

in Alaska.

This July, however, Secretary of Agriculture Ann Veneman announced a completely

new rule that gives the decision-making for road building to state governors,

to localize the process and to reduce further battles in court. “The prognosis

for the 2001 rule is continuing litigation,” she said in a press conference

in Boise, Idaho, on July 12.

| Kerry Vs. Bush: Land Use |

| The debate over federal land management

in the United States covers a wide array of topics, including wildfire protection,

national park maintenance and development of a nuclear waste repository

at Yucca Mountain. Here’s how the candidates face off on some of these

topics. |

| KERRY |

BUSH |

| Plans to increase the operating budget of the National Park Service by

$600 million in the next five years and ban ATV use in parks

|

Has committed $4.9 billion toward handling the National Park Service’s

maintenance backlog, but provided only $2.8 billion

|

| Would establish Forest Health Councils to evaluate environmental impacts

and fire prevention techniques, and would ban logging in rare and old growth

forests |

Proposed the Healthy Forests Initiative to clear out undergrowth and trees

to decrease fire hazards |

Favors reinstating federal

protection of roadless areas |

Has shifted protection of roadless areas to the states |

| Would require all lessees and users of public lands (farming, mining,

etc.) to return them to their original state |

Promotes a conservation program to restore and protect habitats affected

by farming |

| Opposes creation of a nuclear waste repository at Yucca Mountain in Nevada |

Plans to authorize a nuclear waste repository at Yucca Mountain in Nevada |

Thirty-eight states and Puerto Rico have roadless conservation areas, according

to the Forest Service, though 12 western states contain the vast majority. If

the rule goes forward, state governors will have a year and a half to submit a

management plan, which would then be subject to approval by the secretary. The

review period closes Nov. 15; by mid-August, fewer than 100,000 comments had been

registered.

Several environmental groups argue that the states lack the resources to develop

adequate plans for forest management and to determine the effects of building

roads, which they fear would damage wildlife habitat and streams, as well as lead

to logging and other disturbances to land bordering national parks. An analysis

by the Heritage Forests Campaign determined that more than 20 national parks and

monuments have roadless conservation areas on their borders that might lose protection.

Peter Altman, director of the Campaign to Protect America’s Lands, points

to 1.4 million acres of roadless areas surrounding Grand Teton National Park,

where several projects are proposed for natural gas and oil exploration. Some

of these regions “directly border and in some cases encroach on Yellowstone,”

Altman said at a press conference in July.

Rob Vandermark, co-director of the Heritage Forests Campaign, also pointed out

a maintenance backlog of $10 billion, half of which is for road repair and maintenance

in national lands. “Congress hasn’t given enough to maintain the roads

we have now, so why ask to build more roads?” he said. In June, the House

of Representatives voted not to fund further road building in the Tongass National

Forest, where four projects in previously roadless-restricted areas are in the

final stages of development.

Sen. John Kerry, the Democratic presidential candidate, has stated that if elected,

he would revisit the new roadless rule. And the day after Veneman announced the

Bush administration’s rule change, Kerry unveiled his own $100-million forest

plan. He would shift funding from timber industry subsidies to create a Forest

Restoration Corps and increase funding for firefighting efforts and fuel reduction

around houses. Kerry supports parts of Bush’s controversial Healthy Forests

Initiative, which aims to reduce fire risk, but told the Wall Street Journal on

June 17 that it has “big loopholes.”

In addition to these aboveground issues, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) announced

last year that it would streamline the permitting process for subsurface exploration

at the behest of Congress, to reduce a large backlog. The Government Accountability

Office is reviewing how the land agency makes oil- and gas-related decisions,

and its report is expected next spring. BLM is also in the midst of a controversial

revisit of its 162 land-use plans, some of which date back to the 1970s.

The omnibus energy bill that might further alter the leasing and permitting process

on public lands for oil, gas, coal and geothermal energy has so far stalled in

Congress. Controversial drilling in Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

was dropped from that legislation this year (see story above).

Other federal land management issues — including the designation of national

monuments and wilderness and right-of-way issues such as allowing snowmobiles

in Yellowstone — remain on the horizon for Congress and the next president.

One surprising issue, Brewer says, is maintenance and general upkeep of parks.

Brewer says that excessive costs of fighting recent forest fires have been used

as a rationalization to not fund public lands’ upkeep. “Summer is when

the Forest Service and Park Service get most of the work done,” Brewer says.

“Well, there was no money for it this year. … It’s about as bad

as anybody who’s been around for a while can remember.”

While campaigning at Grand Canyon National Park in August, Kerry said the park

faces a shortfall of over $8 million. He pledged to add $600 million to the operating

budgets of all national parks, partly through mineral rights leases, for which

he proposes raising prices. The Department of Interior, following up on a July

report on improvements to national parks that cited a 20-percent budget increase

since President Bush took office, rebutted Kerry’s comments with a list of

its recent accomplishments and investments in Grand Canyon.

Naomi Lubick

Links:

"Under-reef

pipelines get green light," Geotimes, July 2004

"A loophole threatens

Yucca Mountain," Geotimes, August 2004

"Wide-open

West," Geotimes WebExtra, Aug. 30, 2004

Back to top

The

evolving debate over teaching evolution

As the United States heads into the congressional and presidential elections in

November, few people will be paying close attention to local races, such as who

sits on local or state school boards. But such races can prove exciting or devastating

— depending on a person’s point of view — when watching the ongoing

debate about the teaching of evolution in the classroom.

In the last couple of years, most states have witnessed or been embroiled in debates

over how the theory of evolution should be presented in public schools. Two of

the more recent debates — in Roseville, Calif., and Darby, Mont. — fall

under the “win” column for evolution proponents, as local communities

and school boards rejected moves to include anti-evolution materials, according

to the National Center for Science Education (NCSE).

But a new battle in Kansas is just beginning to brew. In August, the state school

board election turned over to a conservative majority for the first time in five

years. And in a year where the state science standards are under review, “this

bodes ill for the future,” says Eugenie Scott, director of NCSE.

“We’re three meetings into the process of reviewing the state science

standards,” which will go on all year, says Greg Schell, who left his position

as Kansas’ science education consultant shortly after the election. The recent

election affords opponents of evolution at least a 6 to 4 majority, according

to NCSE. Thus, “if we come back with standards similar to the current science

standards, the board [of education] will likely reject them,” Schell says.

One of the Kansas education board members just elected to his fourth term on the

board, Republican Steve Abrams, has said that the standards should solely include

“good science that is measurable, observable, testable, repeatable,”

and that evolution does not meet that definition, according to the Wichita Eagle.

“We’ve been through this before, and it’s just wrong for science

and wrong for the students,” Schell says, referring to the 1999 battle over

the presentation of evolution in Kansas education standards (see Geotimes,

October 1999), which Abrams proposed. “It’s like 1999 all over again,”

Scott agrees, adding that in 1999, the board voted to de-emphasize evolution in

science textbooks. The board, she says, has been split evenly between evolutionists

and anti-evolutionists since then, so “this is the year the conservatives

have been waiting for to make the changes,” a year when an election swings

the board, and thus the presentation of evolution, one way or the other.

Election years are always problematic, Scott says, because “it seems like

we have more local politicians posturing for local groups,” leading to a

tendency for legislative bills and school board bills that affect the teaching

of evolution. One problem in elections is that citizens do not always pay close

attention to whom they elect in local races, such as for school boards, says Judy

Scotchmoor, a former middle school earth science teacher who now works at the

University of California, Berkeley, Museum of Paleontology.

In California as elsewhere, Scotchmoor says, there are local influences trying

to include variations of anti-evolution sentiment in curricula, whether taking

the form of intelligent design, creationism, or the latest — “teaching

the controversy,” which includes teaching purported strengths and weaknesses

of the theory of evolution and teaching that there are “other scientific

alternatives out there.”

The approach anti-evolutionists take to incorporating some form of creationism

in curricula is “evolving,” Scott says. They are “working hard

to present anti-evolution more subtly, as less recognizable,” she says. The

sentiment is couched in terms of “teaching our children to think critically,”

but that method becomes problematic when singling out evolution among the many

scientific theories.

Scott Linneman, a geologist at Western Washington University in Bellingham, Wash.,

who leads seminars for elementary, middle and high school teachers on how to teach

science, says that while the presentation of evolution in the classroom is a political

battle not likely to go away soon, it’s also a personal battle for the teachers.

Many of the teachers he has worked with, he says, have told him that they end

up not teaching the tenets of evolution. And it is not always because of local

or state school board political decisions, but sometimes because they face challenges

and pressure from students, parents and community members. But taking the path

of least resistance will only hurt the students in the long term, Linneman says.

What the science community needs to do, he says, is to arm teachers with ways

to teach “interesting or difficult topics like natural selection,” to

answer difficult questions, and to teach these topics “without getting their

heads chewed off.”

“In a science class, science needs to be taught,” Scotchmoor says, and

not all teachers are prepared to answer questions that can be deeply personal

to students. It would be a shame, she says, for teachers to avoid teaching controversial

topics because they don’t know how to answer questions.

And as the recent election in Kansas shows, “we need to pay attention to

who gets elected everywhere,” Scotchmoor says. On the national level, President

Bush and Sen. John Kerry (D-Mass.) differ in their views. According to his campaign

staff, Bush believes ideologically that both evolution and creationism ought to

be taught. Kerry’s platform suggests that he believes only the best science

should be taught.

Whether the race is presidential, congressional or local, people need to be vigilant,

Scott says. “People need to understand how important it is to pay attention

to all races and all policies.”

Megan Sever

Links:

"Kansas rejects evolution,"

Geotimes, October 1999

"Creationism

in a national park," Geotimes, March 2004

"Textbook battle

over evolution," Geotimes, September 2003

"Evolution opponents

score in Georgia," Geotimes, November 2002

Back

to top

Funding

and the fate of NASA

After the Columbia

Space Shuttle disaster in February 2003, NASA was left in limbo — with all

planned shuttle missions grounded, and the future of human space flight uncertain.

Then, in January of this year, President Bush announced a bold proposal reaffirming

the United States’ commitment to human space exploration and calling for

a complete restructuring of NASA to meet those goals. The new plan is the largest

change to the U.S. space program since President John F. Kennedy called for a

manned mission to the moon in 1961. However, with a projected 2004 federal deficit

of $450 billion and little to no increases in the NASA budget, some pundits are

questioning the wisdom and feasibility of such a plan.

After the Columbia

Space Shuttle disaster in February 2003, NASA was left in limbo — with all

planned shuttle missions grounded, and the future of human space flight uncertain.

Then, in January of this year, President Bush announced a bold proposal reaffirming

the United States’ commitment to human space exploration and calling for

a complete restructuring of NASA to meet those goals. The new plan is the largest

change to the U.S. space program since President John F. Kennedy called for a

manned mission to the moon in 1961. However, with a projected 2004 federal deficit

of $450 billion and little to no increases in the NASA budget, some pundits are

questioning the wisdom and feasibility of such a plan.

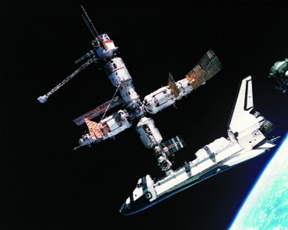

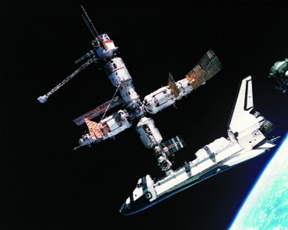

In June 1995, the Space Shuttle Atlantis

docked with the Russian space station Mir for the first time — paving the

way for the International Space Station now in orbit. Under Bush’s new space

exploration plan, NASA will retire the Space Shuttle after the completion of the

Space Station in 2010. Image courtesy of NASA.

“Today we set a new course for America’s space program,” Bush said

in his unveiling speech at NASA headquarters in Washington, D.C. His plan calls

for a permanent base on the moon by 2020, which will serve as a stepping stone

towards the human exploration of Mars. After the completion of the International

Space Station in 2010, NASA will abandon the Space Shuttle program in favor of

developing a new spacecraft, called the Crew Exploration Vehicle. The new vehicle

will continue to service the space station after the shuttle is retired, but its

main purpose is for space exploration, Bush said.

Bush’s focus on human space exploration is a significant departure from the

“faster, better, cheaper” philosophy championed in the 1990s under President

Clinton’s administration. Clinton trimmed NASA’s budget, and former

NASA administrator Dan Goldin pushed for smaller unmanned missions on shorter

timescales. The faster, better, cheaper approach produced some remarkable successes

such as Mars Pathfinder and Mars Global Surveyor, but also turned out embarrassing

failures such as Mars Polar Lander and Mars Climate Orbiter.

These smaller missions generally cost hundreds of millions of dollars and took

three to four years to complete, compared with decade-long projects with billion

dollar price tags such as Galileo and Cassini. Analysts’ estimates for the

cost of Bush’s new plan vary, but a similar plan, put forward by his father

as president, was estimated to cost between $400 billion and $500 billion over

an extended period. Congress did not approve that plan.

In this election year, some politicians, including presidential hopeful Sen. John

Kerry (D-Mass.) and former astronaut Sen. Bill Nelson (D-Fla.), have expressed

reservations about the cost and funding level of Bush’s new plan. In a written

response to questions from Space News, Kerry wrote, “there is little to be

gained from a ‘Bush space initiative’ that throws out lofty goals, but

fails to support those goals with realistic funding.”

In 2004, NASA received $15.4 billion. Bush wants to slightly enlarge NASA’s

budget in the next few years, with additional revenue coming from the completion

of the International Space Station, the end of the shuttle program and interagency

cuts. Bush also created the President’s Commission on Implementation of U.S.

Space Exploration Policy to explore ways to reduce the cost and ensure the success

of his vision for space exploration.

The commission suggested that NASA streamline its bureaucracy, increase privatization

and encourage the commercialization of space. “We would like NASA to try

to leverage investment to get even greater outside involvement,” says Laurie

Leshin, the director of the Center of Meteorite Studies at Arizona State University

and a member of the White House commission that produced the report. She points

to prize-based incentives like the privately funded Ansari X Prize that have captured

public attention and resulted in millions of dollars of private investment. NASA

has begun to adopt some of the commission’s recommendations, although it

is unclear how much money the changes will save.

NASA would have saved some money earlier this year when it announced (citing safety

concerns) that it would not launch a shuttle mission intended to repair the aging

Hubble Space Telescope. Following intense public outcry, however, NASA is now

planning a robotic repair mission, which is estimated to cost at least $1 billion.

“But who knows how much it is actually going to cost,” says Kevin Marvel,

deputy executive director of the American Astronomical Society. “In the best

scenario, Congress may decide Hubble is of such national importance that it will

come up with new money to fund the project.” If Congress does not fully fund

the repair mission, it is likely that NASA will take funds from its space exploration

program, Marvel says.

So far, Congress has been tightfisted concerning space spending. In July, a Republican-led

House subcommittee voted to cut NASA’s budget by 7 percent to $15.1 billion

— $1.1 billion less than what the president requested. The vote coincided

with the 35th anniversary of Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the moon. The

bill would fully fund the Space Shuttle and Mars exploration programs, but would

cut other programs, such as the Crew Exploration Vehicle.

The White House has threatened to veto the House’s spending bill. “The

Senate will probably bring up their bill sometime in October,” says Sam Rankin,

the chairman of the Coalition for National Science Funding. “We have heard

some rumors that [the Senate] bill might do better than the House, but the funding

might still not meet the president’s request.”

Nevertheless, the public appears supportive of President Bush’s new space

directive. A recent Gallup poll, funded by the Coalition for Space Exploration,

reported that 79 percent of Republicans and 60 percent of Democrats support the

plan.

Jay Chapman

Geotimes intern

Link:

"Space Exploration and Development: Why Humans?," Geotimes,

June 2004

Back to top

Climate

tipping point

In July,

the city of New York and eight states joined together in an unprecedented lawsuit

to argue that global warming is a nuisance to the public and a threat to local

economies. The suit specifically takes aim at five major power producers and

their carbon dioxide emissions. While the outcome of the lawsuit remains to

be seen, the action itself highlights the strategies states and smaller governmental

organizations are taking in the absence of a unified federal policy on emissions.

It could also be a harbinger of a shift in the societal response to global climate

change.

In July,

the city of New York and eight states joined together in an unprecedented lawsuit

to argue that global warming is a nuisance to the public and a threat to local

economies. The suit specifically takes aim at five major power producers and

their carbon dioxide emissions. While the outcome of the lawsuit remains to

be seen, the action itself highlights the strategies states and smaller governmental

organizations are taking in the absence of a unified federal policy on emissions.

It could also be a harbinger of a shift in the societal response to global climate

change.

New York State Attorney General Eliot

Spitzer announces to reporters the recent lawsuit by eight states and the city

of New York that charges five major power companies with creating a public nuisance

through carbon dioxide emissions.Image courtesy of the Office of the Attorney

General of New York.

“The science has been there for a while,” says Lisa Dilling, a project

scientist at the Environmental and Societal Impacts Group of the National Center

for Atmospheric Research in Colorado. “We already are seeing climate change,”

she says, citing, for example, Alaska, where millennia-old frozen tundra is

now thawing. However, the costs associated with the regulation of contributing

behaviors and arguments over the rate and geologic history of climate change

have hindered movement toward a solution.

In the United States, most measures to reduce emissions of carbon dioxide are

strictly voluntary for now. While major oil companies, including Shell Oil,

ExxonMobil and BP, have statements on the threat of global climate change, and

either fund or conduct research on carbon sequestration and other applicable

measures, only about 50 major companies have signed on to the Bush administration’s

Climate Leaders program. About a dozen of those companies have made nonbinding

pledges to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by varying amounts in five to 10

years, and a handful of others have pledged reductions between 4 percent and

40 percent by 2012.

The Kyoto Protocol, which President Clinton signed in 1998 but from which President

Bush withdrew, would have set U.S. goals overall at a 7-percent reduction. The

European Union, Canada and more than 150 other nations have signed and pledged

to reduce their greenhouse gases and carbon dioxide emissions by varying amounts

by 2012. Russia is considering signing, in order to join the World Trade Organization.

These measures abroad may come home to the United States because companies wishing

to operate internationally will have to comply with their host country’s

regulations, say some industry watchers.

| Kerry

Vs. Bush: Alternative Energy |

| Although the leading presidential

candidates have offered little in the way of a national climate change policy,

they do have something to say about alternative energy solutions and their

potential impact on the environment. |

| KERRY |

BUSH |

| Proposes investing $10 billion in the development of cleaner-burning

coal power

|

Implemented the Clean Coal Power Initiative to demonstrate advanced

coal-based power-generation technologies

|

| Proposes an increased use of domestic ethanol and biofuels on the order

of 5 billion gallons by 2012 |

Favors increased use of domestic ethanol and biodiesel using a credit

trading system |

| Opposes Bush’s proposed research forum for nuclear energy |

Favors funding for the development of nuclear fusion as a viable energy

source |

| Wants 20 percent of U.S. electricity derived from renewable energy sources

by 2020 |

Would provide tax incentives for the use of alternative energy (wind,

solar, etc.) in residential areas |

| Supports development of a Hydrogen Institute to research alternative-fuel-based

vehicles, promising $5 billion in funding |

Endorses the development of hydrogen-fuel-based cars through the Hydrogen

Fuel Initiative, promising $1.7 billion in funding |

| Will provide tax incentives to buyers and manufacturers of alternative

fuel vehicles |

Will provide tax incentives to buyers of alternative fuel vehicles

|

“We can see politically how this is beginning to shape up in the same

way that issues with sulfur dioxide did in the 1980s,” says John Stowell,

vice president of federal affairs, environmental strategy and sustainability

for Cinergy, an Ohio-based electricity company that is one of the defendants

in the states’ recent global warming lawsuit. “The politics are coming

together. We can’t really predict how it will go,” he says. “We

have to get ready for what our CEO is calling the carbon-constrained world.”

Cinergy burns 30 million tons of coal and emits 70 million tons of carbon dioxide

a year, and has pledged to reduce its emissions by 5 percent by 2012. Currently,

the company plants trees to offset some of those emissions. Stowell says that

Cinergy has promised to invest a total of $21 million over seven years in other

projects, tracked by Environmental Defense, an activist group acting as a third-party

verifier. Stowell notes that some pressure comes from investors, who are both

protecting their future assets and investing according to their own ethics,

something other companies are experiencing as well.

International companies, such as BP and Ford, “are probably trying to get

ahead of the curve,” says William Cline, an economist at the Institute

for International Economics and the Center for Global Development in Washington,

D.C. “[They] may foresee more draconian and costly actions later,”

he says, with the probable adoption of regulatory structures, no matter what

baselines are set.

The other side of that economic argument, Cline says, is that people often are

loathe to spend money now on such a long-term, seemingly intractable problem

as climate change. That concept lost him the debate at a recent gathering of

leading economists called the Copenhagen Consensus, held in May in Denmark,

to determine what global problems are best for investment: Climate change came

in dead last.

For such an international problem, says Barry Rabe, an environmental policy

expert at the University of Michigan, states have played a surprisingly large

role, as have cities. California, Minnesota, New Jersey and others have renewable

power portfolios or emissions regulations for reasons as diverse as loss of

tourism from shorter ski seasons and shoreline encroachment from rising sea

levels. He says that some northern states are talking with Canada about possible

alternative energy deals, including buying hydropower from Manitoba.

An increasing public awareness of climate change and more states’ actions

could bring the issue more to the fore in Congress, Rabe says, where efforts

on Capitol Hill have been on the back burner since the failure of the Lieberman-McCain

Climate Stewardship Act in the Senate last October. Citing bipartisan support,

McCain has promised to reintroduce the legislation in the next year.

At the Democratic presidential convention in July, the party said it would strengthen

the Clean Air Act among other measures to address climate change (see story

below). Democrats also pledged to “restore American leadership on this

issue as well as others,” suggesting an “abdication” on the part

of the Bush administration with regard to climate change issues at an international

level. Similarly, environmental groups have criticized the Bush administration

of emphasizing the uncertainties in the science instead of acting to curb emissions.

In August, the administration seemingly took a turn in its position: A routine

report to Congress, submitted by Energy Secretary Spencer Abraham, Secretary of

Commerce Donald Evans and the president’s science policy advisor John Marburger,

acknowledges that carbon dioxide “is the largest single forcing agent of

climate change,” and that human emissions and land-use changes are important.

Marburger told the Washington Post, however, that the report has no impact

on policy. The month before, Abraham laid out the Bush administration’s approach

to climate change in the July 30 Science. “Although climate change

is a complex and long-term challenge,” he wrote, “the Bush administration

recognizes that there are cost-effective steps we can take now.”

Where Europe is starting on the policy path to curbing emissions, the Bush administration

has emphasized research to change the technology, Cline says. “Part of

the question is: What is the right balance of the two?”

Naomi Lubick

Links:

"Climate

change report reexamined," Geotimes WebExtra, Aug. 28, 2003

"Humans impact

the climate, says AGU," Geotimes WebExtra, Dec. 19, 2003

Back to top

Clean

air deadlock

In the United

States, coal-fired power plants emit more than 60 percent of the nation’s

sulfur dioxide, more than a quarter of its nitrogen oxides, more than a third

of its mercury and 40 percent of its carbon dioxide. These pollutants pose a threat

to public health — shortening life spans and increasing asthma, cancer and

respiratory disease incidences.

In the United

States, coal-fired power plants emit more than 60 percent of the nation’s

sulfur dioxide, more than a quarter of its nitrogen oxides, more than a third

of its mercury and 40 percent of its carbon dioxide. These pollutants pose a threat

to public health — shortening life spans and increasing asthma, cancer and

respiratory disease incidences.

While the 34-year-old Clean Air Act contains regulatory controls for many of these

emissions, some critics say the federal government has not enforced them strongly

enough, while others say the rules are too complicated and need to be streamlined.

The disagreement has led to a standstill on changes to air pollution policy, with

legislation tied up in congressional committees and regulations tied up in the

courts.

Legislation and regulations to reinforce

or replace the Clean Air Act have been tied up in Congress and the courts. Image

courtesy of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

The most visible new legislation is President Bush’s Clear Skies Initiative.

Proposed in 2002, the plan would set a national cap on emissions of sulfur dioxide,

nitrogen oxides and mercury, allowing power plants to trade allowances to meet

the cap. But the proposal has been met with opposition from Democrats and Republicans

alike in this election year, and its introduction has triggered a slew of other

proposals for keeping the nation’s skies clean.

According to the Bush administration, by 2018, Clear Skies would cut sulfur dioxide

emissions by 73 percent, nitrogen oxides by 67 percent and mercury emissions by

69 percent, compared to current emission levels. But that’s not as much as

many groups say could be gained by enforcing the Clean Air Act laws already on

the books: According to the Sierra Club, by 2018, the Clear Skies Initiative would

actually allow 1 million tons more of sulfur dioxide, 450,000 tons more of nitrogen

oxides and 9.5 tons more of mercury than would be allowed under rigorous enforcement

of existing Clean Air Act programs.

The Clear Skies Initiative was “a terrible piece of legislation and there

was no way that people concerned about the environment on either side of the aisle

were going to do anything with it,” says Leon Billings, president of the

Clean Air Trust. A nonprofit organization formed in 1995 by former Sens. Edmund

Muskie (D-Maine) and Robert Stafford (R-Vt.), the trust aims to educate the public

and policy-makers about the value of the Clean Air Act and to promote effective

enforcement of the act. “The Clean Air Act is a pretty viable statute,”

Billings says. “They’re not enforcing the law where they have the opportunity

to enforce it.”

Introduced in Congress in February 2003, Clear Skies is one of several pieces

of multi-pollutant legislation introduced in the 108th Congress. Other bills include

the Clean Smokestacks Act, the Clean Air Planning Act and the Clean Power Act

— some of which also would regulate carbon dioxide emissions, unlike Clear

Skies. All of the multi-pollutant legislation was eventually referred to committee,

where it remains today.

| Kerry Vs. Bush: Clean Air |

| Each presidential candidate has

offered different solutions to regulating and reducing harmful emissions

from coal-fired plants. |

| KERRY |

BUSH |

| Advocates increased funding for retrofitting existing coal plants to provide

cleaner, safer energy |

Promotes a coal-based, zero-emission electric and hydrogen power plant,

which will reduce greenhouse gases |

| Wants to “eliminate Bush-Cheney rollbacks” on the Clean Air

Act to reduce emissions of carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides

and mercury |

Has introduced the Clear Skies legislation to reduce power plant emissions,

especially mercury, by up to 70 percent over the next 15 years |

| Wants to enforce existing laws limiting corporations’ emissions and

establish a compliance deadline |

Recommends a cap on nitrogen oxides and sulfur dioxide emissions that

cross state borders |

“This is a situation where nothing happening is better than anything they’ve

proposed,” Billings says. Clear Skies “may be reinvigorated for the

next Congress, but it’s dead for this one.”

In the face of such legislative setbacks, the administration has attempted to

implement the plan by other means. “Although we would prefer that Congress

pass the president’s proposed Clear Skies Act, the emission reductions are

so important that we are moving forward to cut emissions administratively,”

wrote Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Administrator Mike Leavitt in testimony

to the Senate Subcommittee on Clean Air, Climate and Nuclear Safety in April.

Last December, EPA bypassed Congress and proposed two regulations (which will

not be finalized until March 2005) that utilize a “cap and trade” system

to regulate the same pollutants as Clear Skies. The first, the Utility Mercury

Reductions Rule, proposed to reduce mercury emissions from power plants to 15

tons by 2018. The second, called the Interstate Air Quality Rule, proposed to

reduce sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides in 29 eastern states and the District

of Columbia, to help downwind states reach fine particulate matter and ozone standards

that have not yet been met.

The administration also acted to modify the new-source review, which calls for

coal-fired power plants to install the latest pollution-control technologies —

such as smokestack scrubbers that can now reduce emissions by up to 95 percent

— any time they made renovations or upgrades that would increase emissions.

Appended to the Clean Air Act in 1977, new-source review has remained unpopular

with utility companies, which have claimed the regulations are not clear on when

the rule actually applies, and that such renovations are costly. By the late 1990s,

EPA had found that the regulations had been systematically violated over the previous

two decades, so along with the Justice Department, it opened cases against many

of the largest utility companies in the country.

Those enforcement cases, however, may now be negated by actions taken by EPA under

the Bush administration in August 2003. The agency attempted to drastically raise

the cutoff for upgrades that can be considered routine maintenance — regardless

of whether or not the upgrades would increase emissions — thus exempting

the vast majority of future renovations from new-source review.

Sen. John Kerry (D-Mass.) has said that these rules allow plants to invest millions

of dollars in new equipment with the potential to increase pollution without notifying

EPA or installing any additional emissions controls. The Democratic presidential

candidate’s energy plan proposes to leave new-source review intact and to

invest $10 billion over the next decade to update coal-fired power plants with

pollution controls.

“Relaxing pollution regulations to legalize harmful smokestack emissions

that have been illegal for decades is like relaxing accounting rules to solve

the Enron fiasco,” said New York State Attorney General Eliot Spitzer in

a statement on the administration’s proposed changes to new-source review.

He joined with the attorneys general of 13 other states, the District of Columbia

and many cities, in charging the Bush administration with a violation of the Clean

Air Act. Last December, two days before the regulatory change was to take effect,

a U.S. Court of Appeals judge blocked implementation while the lawsuit was in

progress. A final decision from the court is not expected until late 2004 at the

earliest — and most likely after the elections.

Sara Pratt

Geotimes contributing writer

Link:

"In search of

the mercury solution," Geotimes, August 2003

Back to top

Web exclusive!

Water

worries

From ongoing drought in the West to groundwater depletion in the central states

to declining water quality in the East, the United States faces a host of water

issues that have taken years to develop — and very well may take years

to solve. Although these problems are largely local, federal policy and management

plays more of a role than voters may realize.

"The bad news is that there are many water challenges facing the U.S. in

both the short term and long term," says Peter Gleick, director of the Pacific

Institute in Oakland, Calif. In the short term, he says, "the western U.S.

is in a very, very severe drought. … The Colorado River is as low as it's

been in recorded history, and we're not managing that well." Last year, California

farmers came to a long-deliberated settlement with the Department of Interior

to cut their use of Colorado River water to their legal allotment because of growing

demands by other users. Gleick calls the Colorado River and its federal disbursement

"a perennial problem," but the long-term issue, he says, will be climate

change. The most severe impacts will be on water, from its availability to its

quality, he says, "and water managers are not yet getting the message that

they have to deal with climate change."

Other regional problems in the West, where federal bodies control most water resources,

include the fight over the Klamath River in the Pacific Northwest. Those affected

by water levels in the river include salmon and other fish, farmers who claim

the water for agricultural use, and Native Americans with treaty rights to both

water and fish. Jonathan Overpeck, director of the Institute for the Study of

Planet Earth at the University of Arizona, calls the Klamath a "great example

where you don't have a severe drought situation in hand, but you already have

a severe conflict. … There is a lot of water there, but obviously not enough."

But the West is not the only U.S. region that faces water troubles. Scientists

have traced oxygen depletion (or hypoxia) in the Gulf of Mexico, leading to a

dead zone, to pesticide runoff in the Mississippi River (see Geotimes,

October 2003). The Ogallala aquifer in the Midwest is slowly being depleted

(see Geotimes, May 2004).

And in the East, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) continues to issue water-quality

reports that are less than positive.

David Wunch, New Hampshire's state geologist and a division director for the National

Ground Water Association, says quality issues in groundwater and surface water

are worrisome, including "the ever-increasing amount of chemicals we are

detecting in our water supplies" from runoff. Along with quality issues,

Wunch says, "the East Coast also has sustainability issues," owing to

saltwater-bounded groundwater sources for burgeoning coastal populations.

Wunch and others worry about the loss of funding for long-term water monitoring

by USGS. "The budget to keep the Water Resources program running is decreasing,"

he says, and with rising costs, the actual money USGS has to spend on streamflow

monitoring means "we are losing a lot of these stations — and groundwater,

surface water, they are all part of the same cycle."

As Congress decides whether and how much to continue funding USGS water research,

a bill introduced in 2003 to establish a National Water Commission, the first

since the 1970s, remains stalled.

Tanya Heikkila, an assistant professor of public affairs at Columbia University,

says that water issues probably will not be a major factor in the presidential

campaign. "On the individual voter's screen, people are more familiar with

Iraq than they are with water management," Heikkila says. She conjectures

that voters also may not realize the importance of water issues to the presidential

campaign "until somebody gets elected," and the connection between the

president and the administrators that carry out policy becomes clearer. "But

I do think the western states are going to look to the federal government for

some guidance on these issues," she says, as will other regions, such as

the Chesapeake Bay watershed, that are facing water-quality problems that cross

state borders.

"These aren't easy issues," Gleick says, "but it's the 21st century,

not the 20th century anymore, and the way we think about water has to change."

Naomi Lubick

Links:

"First

dead zone forecast," Geotimes, October 2003

"Western

aquifers under stress," Geotimes, May 2004

"Tracking

contaminants down the Mississippi," Geotimes, May 2004

Additional

Links:

Official

campaign Web site for George W. Bush

Official

campaign Web site for John Kerry

AGI

Government Affairs Program for more on election issues and past updates on

legislation

And check out past

Political Scene columns at the Government Affairs Archive

and on the Geotimes

story Archive.

Back to top

Untitled Document

In the 36

years since the discovery of oil at Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, environmentalists and

the petroleum industry have argued over how much federally owned land on the

North Slope, if any, should be opened for oil and gas exploration. The debate

has left policy-makers trying to weigh the potential gain of extracting petroleum

against the environmental impact of drilling in a relatively pristine ecosystem.

In the 36

years since the discovery of oil at Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, environmentalists and

the petroleum industry have argued over how much federally owned land on the

North Slope, if any, should be opened for oil and gas exploration. The debate

has left policy-makers trying to weigh the potential gain of extracting petroleum

against the environmental impact of drilling in a relatively pristine ecosystem.

The U.S. federal

government manages 454 million acres of land, about 20 percent of the country’s

landmass, with most of this acreage in the West. Over the past year, debate over

management of federal lands has intensified, with topics such as oil and gas exploration

and production, wildfire protection and most recently the Bush administration’s

revision of the “roadless rule” entering the political spotlight.

The U.S. federal

government manages 454 million acres of land, about 20 percent of the country’s

landmass, with most of this acreage in the West. Over the past year, debate over

management of federal lands has intensified, with topics such as oil and gas exploration

and production, wildfire protection and most recently the Bush administration’s

revision of the “roadless rule” entering the political spotlight. After the Columbia

Space Shuttle disaster in February 2003, NASA was left in limbo — with all

planned shuttle missions grounded, and the future of human space flight uncertain.

Then, in January of this year, President Bush announced a bold proposal reaffirming

the United States’ commitment to human space exploration and calling for

a complete restructuring of NASA to meet those goals. The new plan is the largest

change to the U.S. space program since President John F. Kennedy called for a

manned mission to the moon in 1961. However, with a projected 2004 federal deficit

of $450 billion and little to no increases in the NASA budget, some pundits are

questioning the wisdom and feasibility of such a plan.

After the Columbia

Space Shuttle disaster in February 2003, NASA was left in limbo — with all

planned shuttle missions grounded, and the future of human space flight uncertain.

Then, in January of this year, President Bush announced a bold proposal reaffirming

the United States’ commitment to human space exploration and calling for

a complete restructuring of NASA to meet those goals. The new plan is the largest

change to the U.S. space program since President John F. Kennedy called for a

manned mission to the moon in 1961. However, with a projected 2004 federal deficit

of $450 billion and little to no increases in the NASA budget, some pundits are

questioning the wisdom and feasibility of such a plan. In July,

the city of New York and eight states joined together in an unprecedented lawsuit

to argue that global warming is a nuisance to the public and a threat to local

economies. The suit specifically takes aim at five major power producers and

their carbon dioxide emissions. While the outcome of the lawsuit remains to

be seen, the action itself highlights the strategies states and smaller governmental

organizations are taking in the absence of a unified federal policy on emissions.

It could also be a harbinger of a shift in the societal response to global climate

change.

In July,

the city of New York and eight states joined together in an unprecedented lawsuit

to argue that global warming is a nuisance to the public and a threat to local

economies. The suit specifically takes aim at five major power producers and

their carbon dioxide emissions. While the outcome of the lawsuit remains to

be seen, the action itself highlights the strategies states and smaller governmental

organizations are taking in the absence of a unified federal policy on emissions.

It could also be a harbinger of a shift in the societal response to global climate

change.  In the United

States, coal-fired power plants emit more than 60 percent of the nation’s

sulfur dioxide, more than a quarter of its nitrogen oxides, more than a third

of its mercury and 40 percent of its carbon dioxide. These pollutants pose a threat

to public health — shortening life spans and increasing asthma, cancer and

respiratory disease incidences.

In the United

States, coal-fired power plants emit more than 60 percent of the nation’s

sulfur dioxide, more than a quarter of its nitrogen oxides, more than a third

of its mercury and 40 percent of its carbon dioxide. These pollutants pose a threat

to public health — shortening life spans and increasing asthma, cancer and

respiratory disease incidences.