|

Profiles: News about people from AGI and its 44 member societies

Archive of past Society Page/Profiles stories by date

David Fastovsky: Dinosaur virtuoso

David Fastovsky has played the viola in some of the finest dinosaur fossil sites in the world, a habit that his long-suffering colleagues often mention with a laugh. He even has two violas, he says — “one to bring to the field, and one I wouldn’t.” On a trip to the Gobi Desert in the 1990s, he says, he brought along his field viola, keeping it cool during the day by storing it under his sleeping bag in his tent.

David Fastovsky has played the viola in some of the finest dinosaur fossil sites in the world, a habit that his long-suffering colleagues often mention with a laugh. He even has two violas, he says — “one to bring to the field, and one I wouldn’t.” On a trip to the Gobi Desert in the 1990s, he says, he brought along his field viola, keeping it cool during the day by storing it under his sleeping bag in his tent.

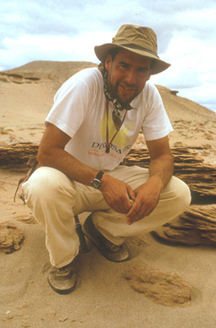

David Fastovsky’s study of the paleoenvironments in which dinosaurs roamed has taken him to dinosaur dig sites from Mongolia to Montana to Mexico. Photograph is by Doug Nichols.

“He really loves music, and it is a big part of his life,” says Marisol Montellano, a longtime friend and a paleontologist at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). She recalls how during a field season in Tamaulipas, Mexico, Fastovsky went across the road from the campsite to practice his viola, “with all the bats and cows and animals around.”

In the badlands of Montana, Fastovsky startled a sleepy team of undergraduates and researchers camping at the Hell Creek site, remembers Peter Sheehan, a paleontologist and head of the geology staff at the Milwaukee Public Museum in Wisconsin. “Suddenly, one night, we had the viola music,” he says, laughing. “You never knew what you’d hear next.”

At one time, Fastovsky says, music nearly became his career. At a crossroads as a senior biology major at Reed College in Portland, Ore., he says, “I wrote myself a list of three categories — what I was interested in, what I was good at, and what I thought would be acceptable.” Those did not necessarily overlap, as in the case of music, he adds. “I was interested in music and was good at it, but I wasn’t sure I wanted to live the life of a musician.”

Paleontology was also on that list, Fastovsky says, “but I knew nothing about it.” Like every other kid, he says, he was interested in dinosaurs, particularly after reading the book All About Dinosaurs by Roy Chapman Andrews, an Indiana Jones-type adventurer and dinosaur hunter who battled bandits in the Gobi Desert in the 1920s. Reed College, however, offered no courses in geology or paleontology. Still undecided about his future career, he went on to graduate school in biochemistry at the University of Illinois, and “lasted for about 10 minutes there,” he says.

Fortuitously, at around that time, he says, paleontologist Robert Bakker published a groundbreaking article titled “Dinosaur Renaissance,” which asserted that dinosaurs were warm-blooded. The article, Fastovsky says, led him to revisit his earlier career analysis and decide to hunt dinosaurs.

With this new plan in mind, Fastovsky applied and was accepted to the paleontology program at the University of California in Berkeley. He quickly learned to handle fossils, and took his first geology course, with mineralogist Hans Rudolph Venk. That class, Fastovsky says, helped him begin to recognize how important sedimentology is to understanding the past events that surround fossils.

Paleontologists often come from biological and zoological backgrounds, but geology is necessary to answer some basic questions, he says. “You can’t make any statement about the distribution of dinosaurs in space or time until you understand the distribution of rocks in space or time.”

Graduating with a master’s from Berkeley in 1982, Fastovsky moved on to doctoral work with sedimentologist Robert H. Dott Jr. at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, and went to work on the sediments at Hell Creek, where paleontologist William Clemens was excavating Tyrannosaurus rex fossils. “I watched them collect dinosaurs, and thought — these people really need some help with their sedimentology,” Fastovsky says.

He also saw an opportunity to put his sedimentology background to work after Walter Alvarez proposed in 1980 that an asteroid impact might have triggered the dinosaur extinctions at the end of the Cretaceous, 65 million years ago. To study the extinction rate, Fastovsky says, he and Sheehan organized an effort of volunteers and other researchers to collect fossils and examine the sediments at the Hell Creek Formation in a large-scale statistically significant way. They wanted to “back out of the sediments” to determine whether the dinosaurs went extinct suddenly.

“You’re never going to be able to demonstrate that dinosaurs were killed by an asteroid — you can’t find bits of asteroid in their teeth or stuck in their eye sockets,” Fastovsky says. “So you have to reconstruct it by other means,” such as determining whether dinosaurs’ species diversity suffered a sudden decline. Fastovsky has continued to examine this question throughout his career, collecting sedimentological and fossil evidence that he says shows that dinosaur diversity reached a high point at the end of the Cretaceous and suddenly decreased — pointing to a rapid extinction.

Now in the geology department of the University of Rhode Island, he has also continued to carve out a niche for himself as a sedimentologist studying mass extinctions — a field in which he nearly stands alone, Sheehan says. “He’s a very dynamic teacher, and it carries over into his research.” Recently completing a five-year tenure as science editor at Geology, Fastovsky also received a 2006 Distinguished Service Award in August from the Geological Society of America.

“I feel like I’m lucky — I get to work on dinosaurs, create environments for them, reconstruct ancient worlds,” Fastovsky says. His latest research will take him back to Mexico, where he’ll work with paleontologists at UNAM to reconstruct the paleoenvironment in which the oldest hadrosaurs in the region once lived. And chances are, he’ll bring along his field viola, too.

Carolyn Gramling

Subscribe

Subscribe