|

GEOMEDIA

Check out the latest On the Web links, your connection to earth science friendly Web sites. The popular Geomedia feature is now available by topic.

ON THE WEB: Stellarium

ON THE WEB: Galaxy Zoo

Seeing stars

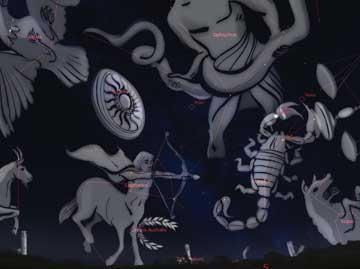

| Celestial objects march across a digital night sky in the free downloadable software Stellarium. |

With Stellarium, a free, downloadable digital planetarium, you won’t just be seeing stars. You’ll see a star-filled sky in real time — just as it might look right outside your own window.

One of Stellarium’s most appealing twists on the classic planetarium is that its skies are photo-realistic, with twinkling stars and shooting stars, and the views are in real time. After opening the program on your computer, you see a view of the sky as it currently appears over a grassy landscape (whether daytime or nighttime), and it slowly rotates as time passes. The point of view is set to a default location (Paris), but users can enter different latitude and longitude coordinates, or choose a city from a number of pre-set cities to check on how the night sky is shaping up in London or Timbuktu. The time of day and even the speed of time are also subject to change, if you’re curious about which stars will be out tonight, or want to watch them sweep across the sky a bit more quickly. There are also several options for resetting the background landscape, including grassy fields, an ocean and the moon.

Be warned: Navigating your way around Stellarium can require a bit more than a sextant (a tool that sailors once used to help chart a course by the stars) or GPS. Several toolbars on the screen help you with some of the more sophisticated features, but basic zooming in and out on a particular star or planet requires knowing which keys control which function. The help button on the lower left toolbar contains a menu of these key functions.

Once you learn the control keys and have set your location, you can also begin to master the rest of the left-hand toolbar, which toggles some of Stellarium’s fun effects. Not only can you view the geometric connect-the-dots of constellations, but you can add an overlay of an artistic rendering of those constellations, find nebulae or superimpose projections of map grid lines on the sky. You can even add a little fog, for realism. The search function, also accessible from the left-hand toolbar, has an autofill feature that can be quite helpful with tricky star names. Once you type in the object you want to view, you are whirled around to it (sometimes those objects are not yet visible in the sky at the current time of day, so you may find yourself staring at the ground, or what’s below the horizon). You can also reset the “sky culture,” alternating the names of constellations between Greek, Inuit or Chinese, for example. On the lower right corner of the screen, another toolbar lets you change the speed of time, moving ahead into the future or backwards to the past to view how the stars were aligned on an important day.

Stellarium has a built-in catalog of more than 600,000 stars, and extra catalogs of more than 210 million stars are also available from the Web site as a separate download. In addition, the program includes a realistic Milky Way, the planets and their satellites and even other solar system objects such as the dwarf planet Ceres and asteroid Juno. (Eris was not included at the time of printing.)

To download Stellarium, visit www.stellarium.org (not to be confused with www.stellarium.com, an unrelated site that offers custom-built planetariums for museums). For more in-depth help with navigating, you can also download a User’s Guide (a PDF file) by following links on the site. Created by research engineer Fabien Chéreau and his team, the latest version of the program (released June 6) is available for Windows, Mac OS X or Linux. For computer-savvy users who want to tinker or add a favorite feature, the program uses OpenGL, an open source code that allows users to adapt it to add new objects, improve features or circumvent bugs, and is hosted at SourceForge, a software development site that hosts open source software projects.

As for the standard user, whether a kid working on a school project or an amateur astronomer wondering what that bright spot above the horizon is, the program is a fun, informative ride across the universe.

Links:

www.stellarium.org

A trip through the Galaxy Zoo

SDSS |

| Is this a spiral or an elliptical galaxy? At the new Web site Galaxy Zoo, anyone can help scientists classify galaxies. (This is a spiral galaxy.) |

Astronomy enthusiasts, take note. Oxford University researchers need your help classifying galaxies. Instead of using your trusty telescope, however, the only tool you’ll need is a computer with Internet access. And you might want a comfy chair, because once you start classifying galaxies and exploring never-before-seen images of our universe at the researchers’ new Web site Galaxy Zoo (www.galaxyzoo.org), you might not want to stop.

Galaxy Zoo allows anyone — whether you fancy yourself an amateur astronomer or have never even peered through a telescope — to participate in real scientific research. With the goal of having their Web site’s users categorize a million galaxies, the creators of Galaxy Zoo hope to learn more about the abundance and distribution of different galaxies in our universe and gain a better understanding of galaxy formation and evolution.

Galaxies are collections of stars, gas and dust held together by gravity, and they come in two main varieties: elliptical and spiral. From a distance, elliptical galaxies look like fuzzy balls of light that are brightest at their centers, becoming dimmer at their margins. Spiral galaxies, such as our Milky Way, look like hurricanes in space with a central mass of light from which long, cloudy, curved arms emanate.

During your first trip to the Galaxy Zoo, create a username and password before proceeding to the Galaxy Tutorial. There, novices learn the basics of galaxy classification: how to distinguish a spiral galaxy from an elliptical one, how to spot two merging galaxies and how to differentiate a clockwise spiral galaxy from a counterclockwise one. After practicing their classification skills, first-time users need to pass the tutorial’s quiz, correctly identifying at least eight out of 15 galaxies, before they can begin to participate in the project. After earning their credentials, participants are free to spend as much time as they like classifying galaxies.

On the Galaxy Analysis page, users will find an unclassified image with all of the classification options lined up next to it. After the user chooses a category, a new image will pop up automatically. The Web site keeps track of all of the galaxies a user classifies, so that he or she can review them again anytime. (It is also a safeguard for the Web site’s creators to be able to check the accuracy of classifications.) Galaxy Zoo’s online forum offers users a place to get help with especially tricky galaxies, share unusual or impressive images they’ve come across or just chat about anything related to astronomy.

In part, the idea for Galaxy Zoo was “born out of my own desperation because I used to do this all by myself,” says Kevin Schawinski, an Oxford graduate student in astrophysics and one of Galaxy Zoo’s creators. For his own research, Schawinski spent a week combing through images from space, classifying a total of 50,000 galaxies. Pleased with the results from this modest sample (the universe is thought to be home to billions of galaxies), he and one of his colleagues at Oxford, astrophysicist Chris Lintott, imagined what they might learn given the opportunity to study a much larger sample of galaxies that covered a larger portion of the universe, Schawinski says.

Access to such a large sample was not a problem. Schawinski and Lintott could use hundreds of thousands of publicly released images from the ongoing Sloan Digital Sky Survey, the world’s largest astronomical survey that is mapping more than a quarter of the sky using a telescope and digital camera based in Apache Point, N.M. Analyzing the images, however, would be a formidable task that would be too time-consuming for one person, or even a few people. And this is one area of astronomy where computers are of little help. “You can try to write an algorithm to try to classify galaxies, but [the computer] can be easily deceived,” Schawinski says.

Humans, in contrast, are “just fantastically good at this” sort of thing, Schawinski says, and “you don’t need to be an expert in astronomy.” Putting a catalog of images online for people to classify from the comfort of their own home seemed like the best way to attract volunteers. Schawinski and Lintott had already seen the concept work for University of California at Berkeley astronomers who created Stardust@home (stardustathome.ssl.berkeley.edu), a Web site where people search through magnified images of material collected by NASA’s Stardust spacecraft to identify individual grains of microscopic interstellar dust.

The gates of the Galaxy Zoo opened July 11, and the response was overwhelming, Schawinski says. In its first few weeks, Galaxy Zoo already had more than 70,000 registered users. These users have already classified a million galaxies. To ensure accuracy, Schawinski and Lintott would like each galaxy to be classified by multiple users, so there is still plenty of work left to do.

As of Aug. 1, Galaxy Zoo’s top classifier, 17-year-old Chris Stevens of Toronto, Canada, had classified more than 50,000 galaxies. “I have spent a fair bit of time classifying, because of all the free time I have since I don’t have a job,” Stevens says, estimating that he spends nearly four or five hours a day classifying galaxies. As a student, he enjoys the opportunity to participate in scientific research “instead of just reading about it,” he says. The project has also reinforced his desire to further his education in astrophysics. A fascination with astronomy also motivated Christopher E. Lorr, a staff sergeant in the U.S. Air Force, to take part in Galaxy Zoo. Lorr, who one day hopes to be an astronaut, has classified hundreds of galaxies. “I spend about 20 to 40 minutes every other day on the site,” he says. A nice benefit of classifying galaxies, he says, is “you get to see some amazing images that few people have ever seen.”

With the success of Galaxy Zoo, Schawinski says its infrastructure could be used in other astronomical projects, especially given the large number of people who seem willing to devote so much of their time to such projects. “I do this because I want to graduate and get a Ph.D.,” Schawinski says. “These people do it because they are fascinated by the universe.”

Links:

www.galaxyzoo.org

stardustathome.ssl.berkeley.edu

Subscribe

Subscribe