Geotimes

Untitled Document

Geomedia

Geotimes.org offers

each month's book reviews, list of new books, book ordering information and new

maps.

Check out this month's On

the Web links, your connection to earth science friendly Web sites. The

popular Geomedia feature is now available by

topic.

Maps: Mapping the seafloor for everyone

Books: Swooning over Scopes: A review of Monkey

Town: The Summer of the Scopes Trial

Books: In the Field with Darwin: A review of Charles

Darwin, Geologist

Mapping the seafloor for everyone

About a year and a half ago, a U.S. Navy submarine bumped into a mountain.

The underwater seamount sits about 550 kilometers (350 miles) south of Guam,

and despite being captured by satellite images, it remained uncharted.

Indeed, the planet’s oceans

remain a blur, at a time when Google Earth and all sorts

of other digital mapping products boast the ability to map a surface with pinpoint

accuracy. Yet slow and steady political and scientific efforts to fill in underwater

mapping blanks may show some promise, scientists cautiously say, as federal

funding and interest seems to be trickling in.

Indeed, the planet’s oceans

remain a blur, at a time when Google Earth and all sorts

of other digital mapping products boast the ability to map a surface with pinpoint

accuracy. Yet slow and steady political and scientific efforts to fill in underwater

mapping blanks may show some promise, scientists cautiously say, as federal

funding and interest seems to be trickling in.

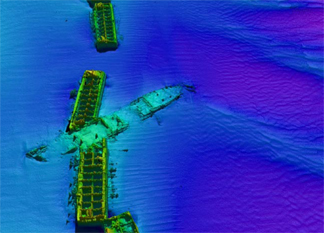

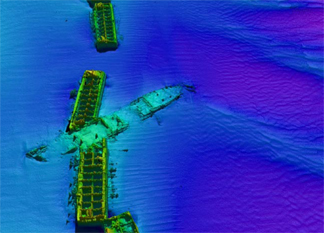

Multibeam sonar data captured this image

of a shipwreck that came to rest atop the concrete chambers that American troops

used to create Mulberry Harbor, in shallow water offshore France, during World

War II. Image is courtesy of Larry Mayer.

In presenting the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) budget

request last February, Vice Admiral Conrad Lautenbacher, the agency’s administrator,

highlighted the Bush administration’s increase in funding to the Department

of Commerce and Transportation to cover “critical mapping, charting and

data improvements.” The requested allocation for fiscal year 2007 added

$5.1 million, for a total of $41.8 million.

In particular, Lautenbacher said, the agency needs vertical set points that

orient maps to the same elevation and spatial grid, which are lacking. Such

“V datum” are “especially important” in the Gulf of Mexico,

he noted, for both resources and ecosystems management, which are responsibilities

carried out by different sections of NOAA, as well as other agencies.

That dispersal of responsibility has created problems historically, says Marcia

McNutt, head of the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. The U.S. Geological

Survey is responsible for mapping land but also has a marine geology division

that in the past did some mapping, and NOAA’s Coast and Geodetic Survey

maps land and nearshore environments for navigational charts. Past turf battles

have broken out over differences in opinion about which agency should do what.

A National Academy of Sciences National Research Council (NRC) report published

in 2004 attempted to settle some of these responsibility issues. The report

laid out a course of action for the federal government to follow, to efficiently

map its sovereign marine territory and fulfill its own responsibilities under

the international U.N. Law of the Sea.

Larry Mayer, an ocean-mapping marine geologist and geophysicist at the University

of New Hampshire in Durham, who chaired the NRC report, says that Japan has

been sinking tens of millions of dollars annually into its marine mapping activities

since the mid-1980s, to collect data in support of the Law of the Sea. Although

the United States may be behind, Mayer says, “NOAA is making an effort”

to work toward fulfilling recommendations made in the presidential Ocean Commission’s

report (see Geotimes, July 2004)

and the NRC report. The federal investment has occurred “slowly, and never

to levels requested in the reports,” he says, but considering the current

tightness of the federal budget, ocean mapping’s status “is not totally

discouraging.”

One big leap forward will come with the conversion currently under way of the

Okianas Explorer, a former naval ship, which will be committed to ocean

exploration and seafloor mapping. But Mayer says that the biggest shifts have

come with technology changes: Increased quality and accuracy now comes at more

affordable costs, and evolving computer algorithms can now crunch data faster.

These jumps have made the prospect of mapping the oceans seem more readily achievable,

he says.

For example, one Canadian scallop fishing company has mapped large swaths of

Canadian territory using a $1 million multibeam sonar system attached to its

boat, Mayer notes. The gains for the company included quartering the time spent

looking for likely habitat to harvest to fill their quota, thus reducing environmental

impacts. Mayer says that U.S. fishermen have yet to adopt the same practice,

perhaps because government-sponsored data they need are more easily available

and free — thus reducing their desire for expanded, more expensive datasets.

Still, Mayer says that recently some U.S. fishermen walked into his office with

portable hard drives to download the data collected by government-sponsored

cruises. The digital format lets sea captains use the data in the same manner

as GPS systems now available in cars.

In an endeavor that will cost millions of dollars a year, Lautenbacher said

that NOAA wants to update and convert paper charts that cover the nation’s

navigable waters to digital formats that can be used in the same fashion, by

the end of 2010. With proposed funds for 2007, the agency would add some 3,000

square nautical miles of more accurate full-bottom coverage data, contained

in 70 charts of all sizes, in addition to the 535 already completed (more than

400 are left to do by 2010).

Navigation, however, is not the only use of ocean maps. From resource extraction

to ecosystems management to homeland security, different map users may collect

different kinds of information at different resolutions for the same region.

Scientists argue that uniform collection criteria would help to create a universal

framework for all map users.

The Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping at the University of New Hampshire

hosted a NOAA-sponsored meeting last month, where different stakeholders began

the process of hammering out such protocols. The eventual goal is a universal

seafloor basemap for all users. A systemic, community-wide view will save time

and money, says McNutt of the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, where

researchers have pioneered underwater mapping techniques at high resolution,

using autonomous robotic vehicles.

McNutt compares the current status of ocean maps to a grassy lawn into which

many different people have mowed their initials: “You might as well go

back and forth and mow the whole land,” in an orderly fashion using the

same criteria, she says. Haphazard ocean mapping, like the crazed scrawls of

a lawnmower run amuck, “isn’t going to save you one instant of time.”

Naomi Lubick

Links:

"Ocean management 101,"

Geotimes, July 2004

"Spinning around the globe online,"

Geotimes, December 2005

Back to top

Book review

Monkey

Town: The Summer of the Scopes Trial Monkey

Town: The Summer of the Scopes Trial

by Ronald Kidd.

Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, 2006.

ISBN 1 4169 0572 3.

Hardcover, $15.95. |

Swooning over Scopes

Glenn Branch

With a plethora of books about the Scopes trial already cluttering the shelves,

including Edward J. Larson’s Pulitzer-Prize-winning Summer for the Gods,

is there really a need for Ronald Kidd’s Monkey Town? Indeed, there

is.

Today as in 1925, the controversy over evolution centers on the science curriculum

of the public school system, and so teenagers are bound to be curious about

its history. Yet treatments aimed at such readers tend to be sober factual accounts,

short on narrative verve and dramatic flair. The exception, of course, is the

play Inherit the Wind, which, though not aimed specifically at the young, nevertheless

quickly became a staple of the high school classroom and the high school stage.

For all its dramatic virtues, however, Inherit the Wind was not intended

as a documentary: John Scopes himself quipped about the introduction of a fiancée

for Bertram Cates, the character based on Scopes — “They had to invent

romance for the balcony set.”

Kidd, too, invents romance for the purposes of his lively and appealing novel:

His narrator Frances swoons over the handsome Scopes, fantasizing about the

day that they will preside over Rhea County Central High School together. But

despite this fictionalization, the setting, personalities and events of the

Scopes trial are presented with scrupulous accuracy, and the few exceptions

are certainly justifiable. For example, Frances is based on real-life Frances

Robinson, who was eight years old at the time of the trial, but Kidd made narrator

Frances older, 15 years old, presumably to connect to the intended teenage audience.

Monkey Town was inspired by a conversation Kidd enjoyed with Robinson

in 1994, nearly 70 years after the trial. The plan to host the American Civil

Liberties Union’s test case of the Butler Act — which forbade teachers

in public schools “to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine

Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended

from a lower order of animals” — in Dayton, Tenn., was hatched in

the drugstore belonging to F. E. Robinson, Frances’s father. Thus Kidd

has a pretext to arrange for Frances to witness or even affect the events surrounding

the trial.

It is, however, a bit of a stretch for Kidd to have Frances help thwart a plot

to run the Baltimore Sun’s caustic reporter H. L. Mencken out of

town on a rail. (There in fact was such a plot, which Robinson’s grandfather

helped to thwart.) A surprising, but delightful, touch in the book is that Frances

eventually befriends Mencken, who is humanized by his love of music and his

devotion to the women in his life.

Not all of the supporting characters receive such development, however. The

only characters who are really fully portrayed are Mencken, Scopes and Frances

herself. But the lack of character development is not a serious flaw in the

book, as the young Frances would not have possessed a great deal of insight

into the personalities of the glittering visitors to Dayton on the basis of

a slight acquaintance, and the intended audience would not be tremendously interested

in any case.

Despite a sometimes didactic tone, Kidd convincingly renders Frances’ struggle

with reconciling her own conflicted feelings about science and religion, culminating

in a theological position that may or may not be deliberately unresolved. During

defense attorney Clarence Darrow’s famously withering examination of politician

William Jennings Bryan, witness for the prosecution, Frances comes to the realization,

“Evolution, like creation, could have taken place in seven days, if the

days were long enough.” But then, when she broaches the subject with her

father, he objects not to the interpretation of the days of Genesis but to the

idea of common ancestry — “You think your Grandpa Haggard came swinging

in on some tree?” — to which she lacks a ready answer.

With its lively dialogue, fast-paced plot and adroit use of historical detail,

Monkey Town is a welcome contribution and important read — especially in

a time where communities across the country still wrestle with the perceived

religious consequences of evolution, and the quality of science education suffers

as a result.

Branch is deputy director of

the National Center for Science Education in Oakland, Calif. E-mail: branch@ncseweb.org.

Back to top

Book review

Charles

Darwin, Geologist Charles

Darwin, Geologist

by Sandra Herbert.

Cornell University Press, 2005.

ISBN 0 8014 4348 2.

Hardback, $39.95. |

In the Field with Darwin

Michael Roberts

The book title “Charles Darwin, Geologist” may seem to be an oxymoron,

as the common perception is that Darwin was a biologist. Sandra Herbert’s

well-produced book of that title, however, documents that Darwin was first a

geologist. Through her many years of work on Darwin’s writings on geology,

as well as a study of his extensive collection of specimens now held in Cambridge,

Herbert does not narrowly focus on Darwin, but rather puts Darwin the geologist

firmly into the context of the 19th century.

Despite all the ink spilled on Darwin, few realize that on the HMS Beagle,

his primary passion was for geology, not biology. On the Galapagos, he wrote

10 times more notes on geology than biology, and he scarcely bothered about

the finches!

Darwin’s active life as a geologist spanned the years from 1831 to 1842.

In 1831, he spent two months studying the geology of Shropshire and North Wales,

partly under the wing of the Reverend Adam Sedgwick (see Geotimes

online, Travels in Geology, October 2005). During the Beagle voyage,

he studied the geology of several locales, which he subsequently wrote up in

three geologic classics, which he published between 1842 and 1846.

On his return to Britain he wrote up his voyage and studied the recent glacial

deposits in Shropshire, Glen Roy, in Scotland in 1838, and in Snowdonia National

Park in Wales in 1842. But after his 1842 visit to the old glaciers of Snowdonia,

he gave up fieldwork, largely because he was unable to walk more than a few

kilometers due to an unidentified illness (thought to be Chagas’ disease)

from his trip around the world (which would plague him until his death).

Because of this illness, his plans for future geologic study, especially of

ancient coral reefs, were thwarted. Instead, he turned to barnacles and then

to The Origin of the Species and other biological studies, which required

no strenuous fieldwork.

In her book, Herbert gives a thematic rather than chronological study of Darwin’s

work, making it clear how important geology was for his evolutionary ideas.

The book’s greatest strength comes from Herbert’s research, in which

she managed to locate most of Darwin’s geological writings. Her study is

based on Darwin’s writings and specimens, rather than on fieldwork in the

areas where Darwin went. As a result, she is not so sure-footed when discussing

the actual localities.

Much of the book seeks to put Darwin’s geologic work into historical context

of geology, general science and the cultural and religious milieu of the day.

Herbert gives both a picture of the state of geology while Darwin was active

in the field and discusses the geologic writings that influenced him. By focusing

on written rather than oral influences, however, she underplays the influence

both John Henslow and Sedgwick had on Darwin’s development as a geologist

before he sailed on the Beagle.

The last two chapters present the importance of geology to the formulation

of Darwin’s evolutionary ideas. Despite the problems of the gaps in the

fossil record he admitted to in The Origin of Species, it is clear from

his notebooks that the idea of fossil succession was very important in convincing

him of evolution in 1837, six months before he posited his theory of natural

selection. Herbert deals with Darwin’s attitude toward geologic time, and

her discussion is invaluable for anyone looking at how Darwin used geology as

a basis for evolution.

This is a useful book, and I hope it inspires others to actually retrace Darwin’s

footsteps for a detailed field history of his geologic research.

Roberts is an honorary research

fellow in history at Lancaster University in the United Kingdom and is a country

vicar. He has a master’s in geology from Oxford and a bachelor’s degree

in theology from Durham.

Links:

"On Darwin's Trail," Geotimes

online, Travels in Geology, October 2005

Back to top

Untitled Document

Indeed, the planet’s oceans

remain a blur, at a time when Google Earth and all sorts

of other digital mapping products boast the ability to map a surface with pinpoint

accuracy. Yet slow and steady political and scientific efforts to fill in underwater

mapping blanks may show some promise, scientists cautiously say, as federal

funding and interest seems to be trickling in.

Indeed, the planet’s oceans

remain a blur, at a time when Google Earth and all sorts

of other digital mapping products boast the ability to map a surface with pinpoint

accuracy. Yet slow and steady political and scientific efforts to fill in underwater

mapping blanks may show some promise, scientists cautiously say, as federal

funding and interest seems to be trickling in.

Monkey

Town: The Summer of the Scopes Trial

Monkey

Town: The Summer of the Scopes Trial  Charles

Darwin, Geologist

Charles

Darwin, Geologist