Geotimes Home | AGI Home | Information Services | Geoscience Education | Public Policy | Programs | Publications | Careers

Parkfield

finally quakes

Parkfield

finally quakes

After 20 years of waiting, the most scientifically watched segment of the San Andreas Fault delivered a large earthquake yesterday.

At about 10:15 a.m. Pacific time, a magnitude-6.0 earthquake shook the tiny

town of Parkfield, Calif., a place that geologists have wired with GPS instruments,

seismometers and a variety of other tools for measuring earthquakes. Several

aftershocks, including at least one that registered 5.0, followed, but no injuries

or deaths were reported in the sparsely populated area, according to the Associated

Press. The temblor was felt throughout the state, from Sacramento, 200 miles

north of Parkfield, to Los Angeles, 200 miles south.

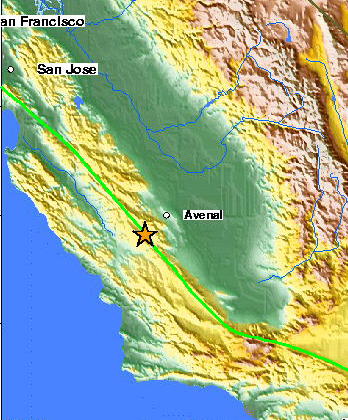

A magnitude-6.0 earthquake struck Central California Tuesday morning on a section of the San Andreas Fault that had been seismically quiet — for almost 20 years too long, according to seismologists' expectations. Researchers from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and elsewhere had heavily instrumented the area for just such an earthquake. Image courtesy of USGS.

The earthquake's epicenter is located 7 miles southeast of Parkfield, and it is the largest Parkfield has felt since 1966 (though the region has experienced small earthquakes since then). In the 1980s, Bill Bakun of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in Menlo Park published the only prediction for the fault ever in the literature: He surmised from the windows of seismic inactivity that the Parkfield segment of the San Andreas Fault was set to rupture in 1986, after having regularly "failed" every 20 or so years — in 1857, 1881, 1901, 1922, 1934 and 1966. The possible time period that Bakun predicted for a "Parkfield-type" earthquake ended in 1993.

"It's the Parkfield earthquake at long last," says Susan Hough, a seismologist at the USGS Pasadena office, "a mere 16 years late, or 12 years outside the window."

"The original prediction was relying too heavily on an extrapolation of a supposedly constant recurrence time," says Chris Scholz, a seismologist at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in Palisades, N.Y. The first several earthquakes of the series were about 20 years apart, but now, the windows of time for the last two earthquakes (1934 to 1966 to 2004) are 32 and 38 years. Scholz also points out that yesterday's earthquake epicenter occurred almost 6 miles south of previous events, and south of where the bulk of the instruments have been located on the fault.

Nevertheless, Hough says, "it's going to be a huge boon scientifically." The instruments to the north of the epicenter, where the earthquake rupture headed, are going to pick up "incredible data," Hough says, "though at this point, who knows what it's going to show." Hough says that she is especially interested to see data from creepmeters installed toward the southern cluster of instruments in Parkfield, "right where this broke along the southern end. The big question is whether there was any precursory creep or deformation," or slow, small movements of the two sides of the fault passing each other.

Scholz notes that the long drill hole known as SAFOD, or the San Andreas Fault Observatory at Depth, which is a part of the EarthScope observation program, is currently at about 3 kilometers (almost 2 miles) depth. Although just short of its goal of 5 kilometers and without instruments, SAFOD will eventually cross over the fault at its 1966 epicenter, in part to directly observe it during such an earthquake. "They're now going to have to wait another 20 to 35 years," he says, if not more, to directly observe a Parkfield-type earthquake.

"It would have been ideal to drill into the fault before this happened and compare before and after," Hough says. But "that's sort of the way things tend to go."

The wait for the next such event may be a long one. One geophysical model for the San Andreas Fault, created by Yehuda Ben Zion of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, shows an increase in time between a series of large aftershock-like events following a large earthquake. "That really fits what we've seen," Hough says. The activity at Parkfield "may be winding down," she says, and the next earthquake in the series may occur 50 years from now.

From a historic viewpoint, this type of earthquake also may have triggered

a larger event in 1857, known as the Fort Tejon earthquake, that ruptured several

hundred miles of the San Andreas Fault starting from Parkfield and moving to

the south. Geologists are watching to see if this most recent earthquake is

such a "foreshock" of a greater event. "If it is, the main shock

is expected within days," Hough says, but the probability is about 5 percent,

"which is small."

Naomi Lubick

Megan Sever contributed to this report.

Links:

The

Parkfield Experiment

USGS

Earthquake Hazards Program

Associated

Press article on USAToday.com

Past

Geotimes related coverage:

"Earthscope:

Reassembling a continent in motion," Geotimes, April 2002

"A new chance for Parkfield,"

Geotimes, September 2002

"San

Simeon earthquake," Geotimes, Dec. 23, 2003

"Magnifying a continent,"

Geotimes, March 2004

"Earthquake

warning tools," Geotimes, October 2003

|

Geotimes Home | AGI Home | Information Services | Geoscience Education | Public Policy | Programs | Publications | Careers |