|

FEATURE — A Changing Climate

2007 Highlights Home page >> A Changing Climate Features >> A Changing Climate Highlights

Change in Climate: Q&A with Margaret Leinen

Carbon dioxide CAFE

A Changing Climate: Other Highlights

Change in Climate: Q&A with Margaret Leinen

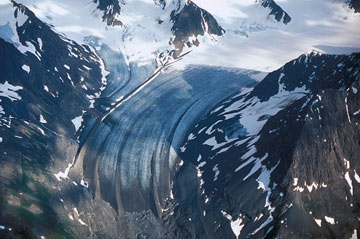

Copyright Bruce Molnia, Terra Photographics |

| This thinning and retreating glacier in Alaska’s Chugach Mountains is referred to as the Five Stripe Glacier for its five prominent medial moraines. Further signs of retreat are the large lateral moraines and the trimlines. |

In October, the Nobel Committee announced that the Nobel Peace Prize had been jointly awarded to former U.S. Vice President Al Gore and the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), praising them for their efforts to “build up and disseminate greater knowledge about man-made climate change.”

The IPCC had released its Fourth Assessment Report on climate change in February, opening with the firm statement that the burning of fossil fuels is “very likely” to be responsible for the current climate change trend. That assessment was the strongest by the IPCC yet, indicating “more than 90 percent” certainty, according to one of its lead authors, Richard Somerville of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography (see Geotimes online, Web Extra, Feb. 2, 2007). Two other chapters, released in April and May, focused on the human and economic impacts of climate change, and mitigation strategies for its effects, respectively (see Geotimes online, Web Extras, April 6, and May 4, 2007).

The impact of the IPCC report — and particularly its first chapter — was “quite dramatic in a couple of ways,” says Margaret Leinen, former assistant director for the geosciences at the National Science Foundation and current chief science officer at Climos, a company that investigates how natural processes can be used to remove carbon from the atmosphere. Leinen talked with Geotimes reporter Carolyn Gramling about how the IPCC report may be transforming the debate over climate change.

CG: Has the release of the report moved things forward?

ML: Definitely. One of the words I’ve used to describe the work was that for scientists it was “stunning” to see the certainty that was ascribed both to climate change itself, which IPCC said was unequivocal, and when they said it was “highly likely” that it was due to human action. You know scientists, we don’t use terms like that lightly, and the IPCC has a rigorous set of guidelines for the wording they use. That was a stunning commentary on the progress in attributing climate change. We’ve really come a long way since the Third Assessment Report [in 2001].

CG: Where has that change in mood been most noticeable?

ML: It had a profound effect, but not only on scientists — if someone like me, who has been in government and associated with the climate change program and is very familiar with the IPCC process, is very surprised and impressed by the degree of certainty, then you can imagine the effect that it had on the rest of the debate. One of the very, very strong impacts it has had is on the private sector. People who are members of private companies and so forth may have been reserved in their judgment about how to interpret words of certainty, and they have a lot of money at stake. And I think they listened closely to the words that were used. In many cases they didn’t want to make changes that would radically affect their way of doing business without that certainty. And we gave them that certainty.

CG: What sort of changes have you seen in the private sector and elsewhere?

ML: We saw the Climate Action Partnership (see Geotimes, April 2007), which represents $4 trillion of the economy, and they said, “Let’s get busy, let’s respond to this,” and then they have some very specific actions they want to take. And in many parts of the private sector, whether finance or manufacturing or whatever, many corporate boards are taking up this issue, asking “What are the implications for our company of this kind of change, and what sorts of responsibilities do we have to our shareholders to look at this?” That’s another major change.

CG: What about at the federal and state levels?

ML: California’s Assembly Bill 32 (which outlines the state’s goal to reduce state greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2020) was passed before the report came out, but what I think has been affected by the report is the degree to which other states have begun to talk with California and work with California in various ways. … I think that while California would certainly have been ahead in setting this pace, the IPCC gave other states’ legislatures a real opportunity to see that it was not wildly out of line in trying to address this. The idea of addressing it now has a degree of support from science that they hadn’t seen before.

The Senate is also really taking this up — it’s difficult to sort out how much of that is a direct result of IPCC and how much [is] a result of a difference in perspective as leadership in the committees changed. But IPCC certainly bolstered the case of those committee chairs and ranking members who felt it was important to look at this more seriously. A lot of the bills have been bipartisan, and I think that says that the certainty of the scientific community had a very profound effect.

CG: The reports from the other two working groups may have gotten a bit less fanfare than the first one did, but what sort of impact do you think they’ve had?

ML: Working Group II’s report also had a very strong effect — you see it less in the news or in terms of the response of the private sector and Congress, but it has had a strong effect on resource management agencies and nongovernmental organizations that concern themselves with the environment and with natural resources. There were a lot of very strong statements about what’s at risk. You may not see [the results of Working Group II] as strongly in the headlines as far as people changing their minds and attribution. [But] state and federal agencies look to this and say, “We’ve got to start thinking about how to deal with this.” So much of the impact is local and regional, because that’s how we see it and need to respond to it.

On the mitigation side, you see strong and powerful activity on the part of the investment community. It wasn’t entirely caused by IPCC, but it has certainly been enhanced since the third report came out.

CG: With the attribution now made, what do you think future assessment reports will focus on?

ML: I hear a lot of discussion in the modeling community about where to go with regional modeling, how to couple models more effectively to look at impacts. I think that will be a major focus in the next few years.

I think the scientific certainty of the report is really going to cause people to say, with respect to Working Group I, where do we go from here? The previous focus of that working group was identifying processes and attribution, and now a lot of the work has been done, but not all of it. So I think that the question will be: How does Working Group I evolve in a post-Fourth-Assessment world?

Links:

"Climate report points finger at fossil fuels," Geotimes online, Web Extra, Feb. 2, 2007

"IPCC report warns of economic, health impacts from climate change," Geotimes online, Web Extra, April 6, 2007

"IPCC says climate change mitigation is affordable," Geotimes online, Web Extra, May 4, 2007

"Speak Now or Forever Hold Your Peace: The Business World Looks at Climate Change," Geotimes, April 2007

Carbon dioxide CAFE

Carolyn Gramling |

| The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in April that carbon dioxide is an air pollutant, and that the Environmental Protection Agency has the authority to regulate it and other greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles. The decision could also pave the way for states to regulate greenhouse gas emissions, and could prompt Congress to set higher fuel efficiency standards. |

After this year, everyone but the auto industry may be breathing a little easier. On April 2, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has the authority to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles under the Clean Air Act — and further ruled that carbon dioxide emissions can be considered an air pollutant (see Geotimes, May 2007). The decision could prompt Congress to set higher fuel efficiency standards for new cars, and has also given a boost to states seeking more stringent emissions regulations than the federal rules.

“It’s a landmark decision,” geologist Jonathan Overpeck of the University of Arizona in Tucson told Geotimes in May. “We were happy to see the Supreme Court recognize the real science behind the issue.”

The decision came eight years after a petition by 12 states, a number of cities and several environmental groups to EPA to regulate carbon dioxide emissions from new cars, a petition that the agency rejected in 2003 by saying that it is not authorized to address climate change, and that carbon dioxide, which occurs naturally in the atmosphere, is not a pollutant.

The Supreme Court case was important not only legally, but also because it set “a mood,” says Kirsten Engel, a professor of environmental law at the University of Arizona who worked with Overpeck and 17 other climate scientists to draft the amicus curiae, a scientific briefing of the case. Because states have been doing the most on climate change so far, she says, the decision is, in a sense, a “validation that they’re working on a real issue.”

To be successful, the plaintiff — in this case, the commonwealth of Massachusetts — needed to show that the failure to regulate was causing damage to the state, and that reducing emissions would reduce that harm, Engel says. In the Supreme Court case, Massachusetts argued that rising sea levels as a result of human-induced climate change was causing ongoing harm to the state by eroding its territory.

“Legally, [the case] did two important things,” Engel says. “It very plainly said that greenhouse gases were air pollutants under the Clean Air Act, which resolved one of the major hurdles for California and other states that are regulating greenhouse gases from vehicles.” Secondly, she says, it resolved the issue of “pre-emption,” which the auto industry has used to argue that state regulation of greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles is pre-empted under the law that governs fuel economy standards. “The Supreme Court opinion stated that there was no pre-emption there; there was an overlap, but no conflict,” she says.

That decision factored into another case that followed on the heels of the Supreme Court’s decision. In September, a federal judge in Vermont upheld the state’s regulations, ruling that states can regulate greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles (see Geotimes, November 2007). In 2005, Vermont had adopted regulations that were modeled on California’s, which called for a 30 percent reduction in carbon dioxide emissions from new vehicles by 2016.

Under the Clean Air Act, California — which was fighting smog when the act was passed — is allowed to set more stringent emissions rules than the federal rules. The state has petitioned EPA for a waiver to enact its own regulations, which are stricter than the national standards. It has yet to receive that waiver, and California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger has threatened to sue if his state does not receive its waiver.

Environmentalists hope that the Supreme Court and Vermont decisions will prompt Congress to increase its Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards. In June, the Senate passed a bill calling for CAFE standards to increase from 27.5 miles per gallon to 35 miles per gallon for new cars by 2020 (see Geotimes online, Web Extra, June 22, 2007); the Vermont regulations would raise CAFE standards to nearly 43 miles per gallon.

Meanwhile, with the responsibility for regulation now placed in EPA’s hands, the auto industry is pushing for an industry-wide standard rather than state-by-state regulations. Twelve states have already passed emissions standards similar to California’s, with at least six more pending. Although the Vermont judge ruled that the industry was able to meet the technological challenges of the higher standards, U.S. automakers have already appealed the Vermont ruling, stating that the case “centers on the critical issue of whether states can regulate a matter — fuel economy — that the law clearly identifies as a federal, national issue,” according to an Oct. 5 statement by the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers.

“There’s a real opportunity here for the federal government,” Engel says. But “in terms of Congress, it’s a little hard to predict. It certainly makes it feel as if regulation of climate change is inevitable, but it seems like we still are waiting for Congress to resolve what approach they want to take.”

Links:

"Supreme Court rules in landmark climate case," Geotimes, May 2007

"Auto ruling paves the way for efficiency standards," Geotimes, November 2007

"Senate passes energy bill," Geotimes online, Web Extra, June 22, 2007

Subscribe

Subscribe